Fans of John Woo's Hong Kong movies have often had a hard time reconciling them with the work he's done in America. Compared with sometimes overly polished entertainments like "Face/Off" (1997) or "Mission: Impossible 2" (2000), Woo's bloodier, more passionate Hong Kong pictures seem to have come not just from another country but another world. You could tell from pictures like the exhilarating "Hard Boiled" (1992) and the devastatingly operatic "Bullet in the Head" (1990) that Woo was deeply in love with the tradition of the Hollywood gangster picture, so deeply in love that he was working in a dream version of the old Hollywood -- in other words, not a long-gone time and place, but one that never existed at all.

Woo's arrival in the real Hollywood, some 10 years ago, seemed to drive an immovable wedge between his old dream Hollywood and the real McCoy. His American pictures have always showcased a certain level of craftsmanship and they always have energy. But the earthy dreaminess of those older Hong Kong movies -- that quality of not belonging to any specific time or place -- seems to have fallen away forever.

Or, at least, almost. "Windtalkers" is a true mainstream Hollywood movie in just about every sense; it doesn't mark a return to innocence for Woo, and we shouldn't expect it to. (As different as the U.S. movie industry is from that of the old Hong Kong, it's likely that Woo's "new" style of filmmaking is almost as much a product of his age and experience as it is of the system under which he works.) But "Windtalkers" is the best of Woo's American movies, and the one with the sturdiest and most direct links to his earlier pictures.

In "Windtalkers," which was inspired by the real-life experiences of Navajo men who were recruited as Marines during World War II and trained to use a secret military code based on their native language, Woo finds a deep and welcoming repository for his favorite themes: the importance of honor among men, even when preserving it means committing unspeakable acts; the incalculable value of true friendship, which should also be preserved at all costs; and the notion that the most moral decisions are not necessarily the most obvious ones, and they're never the easiest.

"Windtalkers" has plenty of flaws. It doesn't have a pleasing structure; the story shambles somewhat aimlessly from scene to scene. And there are long stretches where the movie's brutality is so relentless that it numbs us to the very experiences to which Woo is trying to sensitize us: We need to shut a bit of ourselves off to get through it, which means we're not as fully attentive to the violence as we should be.

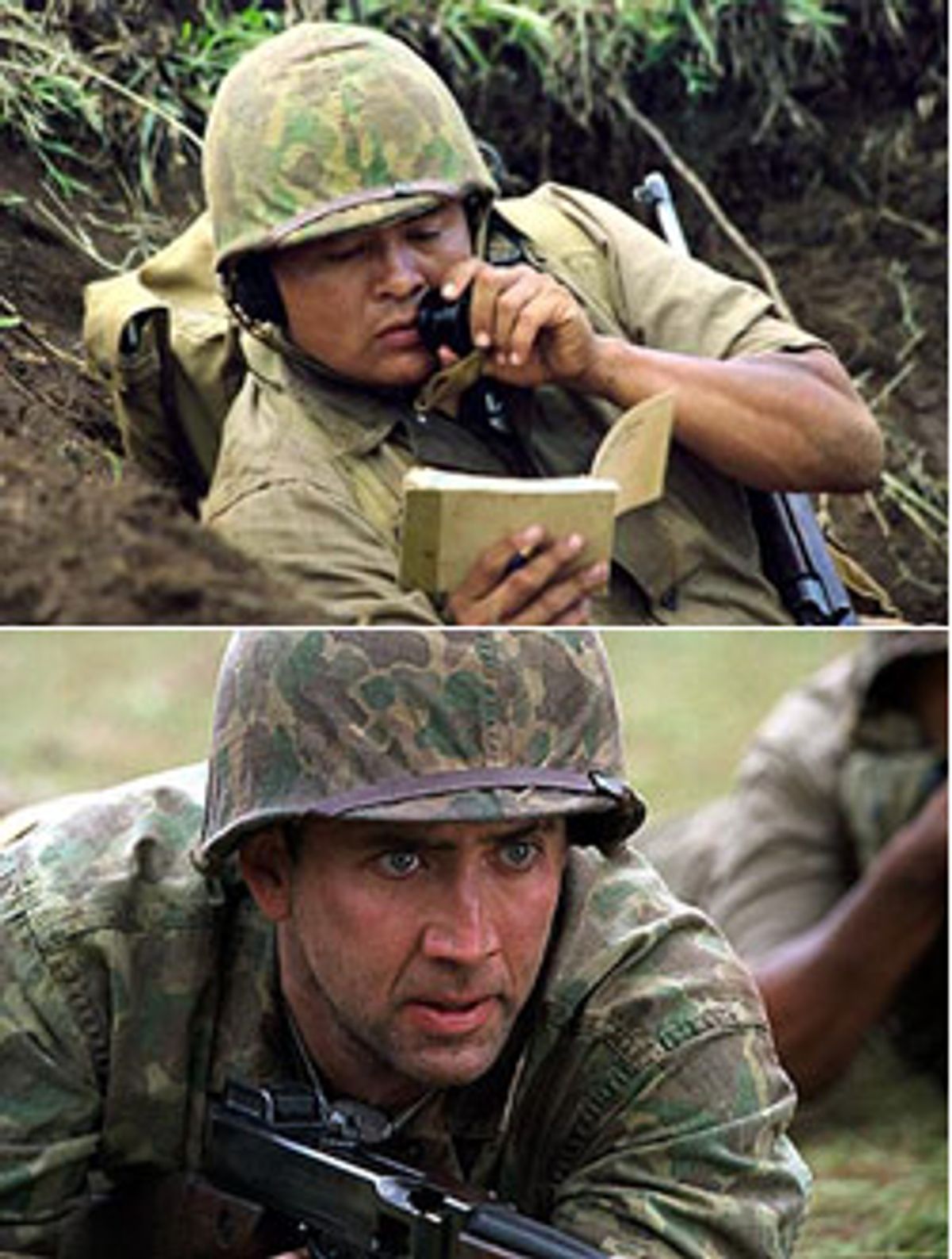

Even so, "Windtalkers" is shapelessly gratifying, the kind of movie that invites you to pick apart its faults even as you have to admit that somehow it hit you where you live. Nicolas Cage plays Marine Sgt. Joe Enders, who's known as a good soldier because he always follows orders, even though doing so resulted in the death of his entire squad during one bloody South Pacific battle. (Most of the movie's action takes place during a later battle, the 1944 clash between U.S. and Japanese forces on the island of Saipan.) Enders survives, recovers and eagerly signs up for a new assignment: He's entrusted with guarding a Navajo "code talker" named Ben Yahzee (Adam Beach) who is trained to transmit messages in the new Navajo-based code.

Similarly, one of Enders' fellow officers, Ox Henderson (Christian Slater), has been assigned to guard Yahzee's pal, Charles Whitehorse (Roger Willie, in a warm but never ingratiating performance), another code talker. The directive is to "protect the code at all costs." The subtext -- one that Woo, wisely, doesn't spell out until late in the movie -- is that protecting the code is not necessarily the same thing as protecting the lives of the men who know it.

In real life, in 1942, 29 Navajo Marines developed a secret code that the Japanese would never crack (and they cracked many); the work of those original code talkers, plus that of the some 300 Navajo Marines who were trained to use the code, has been cited as pivotal in the United States' eventual victory over Japan. During the battle of Iwo Jima alone, Marines using the code transmitted some 800 error-free messages within 48 hours.

You can see why the bare bones of that scenario would appeal to Woo. There are only a few scenes in which we actually see Yahzee and Whitehorse transmitting messages in the heat of battle, and they're thrilling precisely because Woo doesn't load up on them. He's much more interested in the relationships between the men -- and, of course, the action.

"Windtalkers" is generously laden with Woo's characteristic, beautifully choreographed fight sequences; they're also very bloody. You can get away with a lot more violence when you've got the built-in excuse that you're convincing the audience of the horrors of war, but there are times when Woo might have taken a breather. His action sequences are so clear and bright that they would have more impact with fewer throat-slittings and bloodied, twitching stumps.

The real strengths of "Windtalkers" lie in the latitude and guidance that Woo gives his actors, and his great skill at old Hollywood touches that would most likely come off as corny in the hands of lesser directors. Cage has become so adept at playing the tortured, conflicted soul that many of us have become tired of seeing him do it. But he is perfectly cast here, and completely believable as a reluctant war hero who's more no-nonsense than jaded.

When Enders tells Yahzee about the colleagues whose death he was largely responsible for, Yahzee, who hasn't yet been toughened by battle, earnestly urges Enders to do what his people would do: Tell a story about them. With a glare that's halfway between hostile and amused, Enders replies drily, "What a magical pile of Navajo horseshit." But he also lets you see the way the fragile openness of Yahzee's face is working on him. What makes Cage such a terrific and dependable actor isn't just that he knows how to deliver a line but that he visibly responds to the faces -- and all the most subtle, nonverbal cues -- of his fellow actors.

Beach (who, for the record, is a Saulteaux Indian and not a Navajo) is an interesting actor; it might take you three-quarters of the movie to figure out what to make of him. He delivers his lines in a slow, easy drawl, making the men around him, and us, wait for the words to come out. But if it seems like an affectation at first, it ultimately comes to express more things about his character than we might initially think. As we wait for him to finish his sentences, we're temporarily pulled from our world and into his. Woo may exaggerate some of the differences between Navajo culture and the modern world of the 1940s, but those exaggerations (a scene in which Yahzee and Whitehorse say a protective pre-battle prayer, for instance) are more like shorthand than cartoons. With every line, Beach reminds us exactly where Yahzee comes from, opening up a quiet, airy space in the midst of wartime's gruesome, messy horror.

Woo wants to give us plenty to think about, and so he packs every frame with nuanced references to the meaning of honor and the importance of fulfilling our responsibilities toward one another. He's alert to racial issues without being blandly correct about them: The men in Yahzee's company are naturally suspicious of him at first simply because he's an outsider, but later, in a particularly ugly encounter, a fellow soldier needles him for how much he looks like a "Jap."

"Windtalkers," shot by Jeffrey L. Kimball (who also shot "Mission: Impossible 2"), is a handsome film -- sometimes a little too much so. (Woo may be overdoing it when he shows us a pool of blood welling on the body of a dying soldier, gleaming just so.) But the movie's grand sheen does give it an air of regality -- you know exactly where Woo is coming from, which makes even his loftiest ideas that much easier to take. Frances O'Connor has a small role as the nurse Cage falls for and hopes (though he won't admit it) to return to. Women are outside the bubble of Woo's world, but even if they're peripheral, they're not insignificant. They're stand-ins for some vague but vital notion of security, love and calm, existing far away from Woo's man-centric universe, where guys spend their time blowing each other's heads off willy-nilly.

This is retrograde in feminist terms, but then Woo's movies are all about the world of men, viewed through a very specific, traditional, highly movie-centric lens. And there are much worse ways to depict women: O'Connor has something of a saucy flair. She may be keeping the home fires burning, but it's at least partly because she likes the heat.

But my favorite moments in "Windtalkers" are the ones that no other director I can think of would even try to get away with. Whitehorse has brought a wooden flute with him, and he whiles away the evenings away from the other Marines, playing quiet tunes on it in the firelight. Ox comes by and starts making silly, overly friendly chitchat: Is Whitehorse self-taught? he asks. Whitehorse answers him tersely, hanging on to his dignity in the face of the nerdy white guy, but Ox presses on, pulling a harmonica from his pocket and insisting that the two play a duet.

Whitehorse says it won't work, but at Ox's urging, he reluctantly leads off. The mournful wails of his flute are answered by Ox's equally plaintive honeyed tones. It's an eerie call-and-response, but it makes aural sense as a bridge between the two characters.

Of course, you don't need a code talker to discern the message of the scene: Roughly translated, it's something like "Despite their differences, the red man and the white can make beautiful music together."

But there's a secret coded message embedded deep within the obvious one, and it explains why Woo, even when he's fiddling around with some of Hollywood's oldest conventions, still has the power to make movies that resonate. He doesn't work in the same imaginary Hollywood he used to, but he's built a new one for himself on top of the old. In the real Hollywood, as opposed to the dream one, the movies are slicker, the politics more slippery and the financial stakes much, much higher.

In John Woo's Hollywood, sound, light and movement still reign supreme, and the relationships between characters mean everything. As he did in the old Hong Kong days, he still values, above everything else, the things that money can't buy.

Shares