Giving an audience permission to be silly -- blissfully, unashamedly, unreasonably silly -- is one of the happiest things a movie can do. That gift has a lot to do with why the Austin Powers series has earned such goodwill and affection from moviegoers. The pictures function as the equivalent of Austin and Dr. Evil's time machines, offering audiences a chance to zip back to a comic daydream of '60s pop, a theme park of yummy surfaces, where color and expression take precedence over taste. At a time when nearly the totality of our pop past has been strip-mined, recycled and exploited, the Austin Powers series escapes any trace of cynical calculation. The series is the friendliest and most good-natured of recent comedies.

Much of that sweet temperament has to do with Mike Myers' comic style, which, even when he's indulging in the most outrageous scatological humor, feels free of aggression. Myers has described himself as a "situational extrovert." He's not above going for the boffo laugh, but the punch of the jokes comes at you encased in a velvet glove -- a crushed-velvet glove. There's nothing mean-spirited about any of the jokes here. And, as when he's playing Wayne (of "Wayne's World") or Linda Richman, Myers stays remarkably within character, attuned to the minutest quirks of his alter egos (some of the biggest laughs in Austin Powers movies come from the throwaway asides).

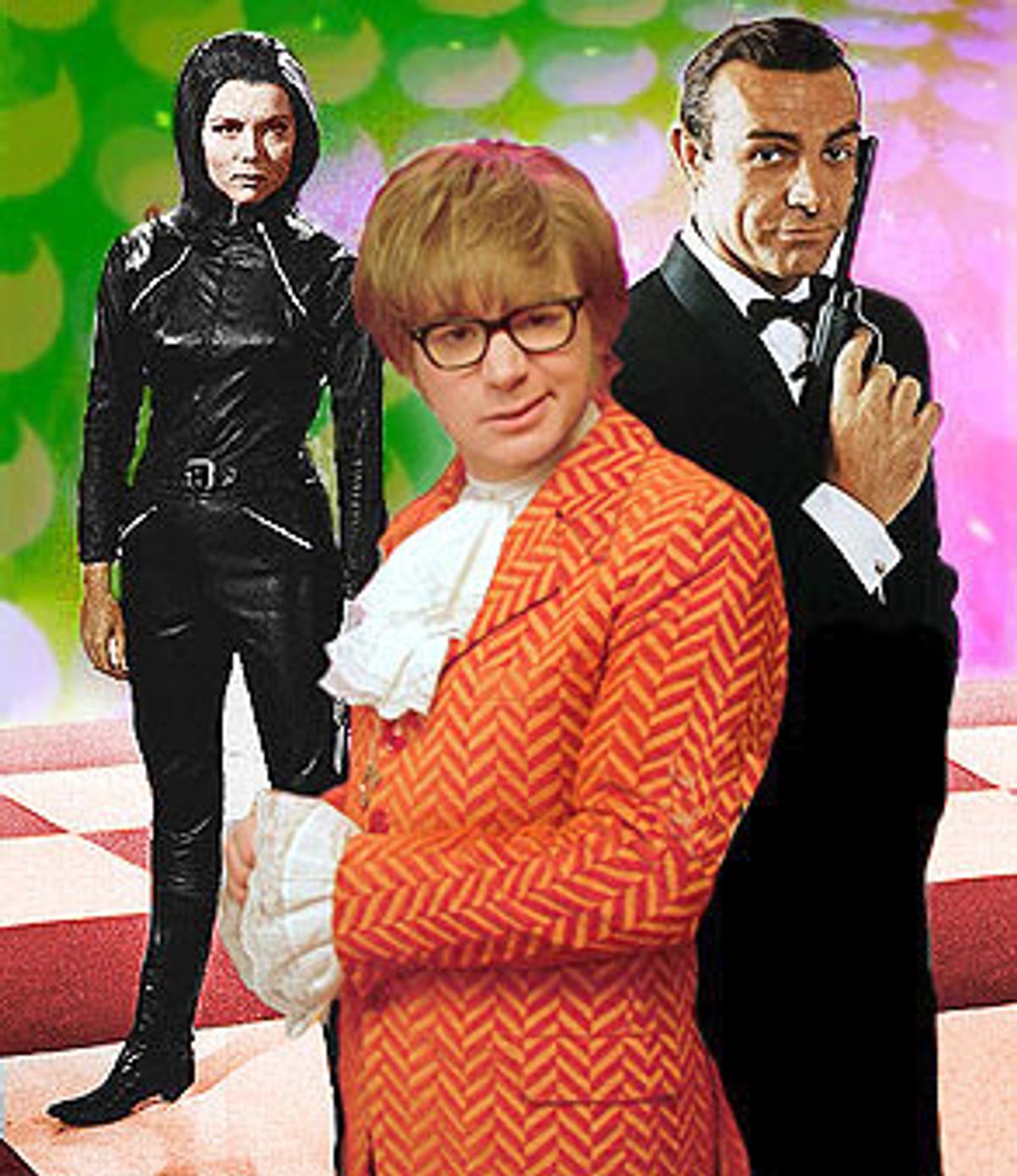

Myers has said that he conceived Austin as a tribute to his English dad (who died in 1991) and to the movies his father loved, James Bond spoofs like the Flint movies with James Coburn and the Matt Helm movies with Dean Martin. Which is to say that Austin Powers is a spoof of a spoof. The irony of their success is that with the Bond movies having become as noisy and undistinguished as any other big-budget action pictures, the Austin Powers movies are now anticipated and greeted with something like the pleasure once reserved for the 007 series. Moviegoers await the appearance of the series' recurring characters, and welcome each familiar convention with affectionate laughter.

Myers has been smart enough and lucky enough to surround himself with people who, like him, dig the comic-book sexiness of '60s pop and aren't troubled by the way that mainstream show biz co-opted the fashions and attitudes of '60s youth culture. The movies exude an infatuation with pop. There's a lot of love in production designer Rusty Smith's take on pop-art bachelor pads and in his versions of the huge villains' lairs that Ken Adam designed for the James Bond movies. The director, Jay Roach, manages to be knowing about the movies he's spoofing without any hint of superiority. (That's becomingly modest when you consider that the Austin Powers movies deliver all the fun that duds like the Flint series and the Matt Helm series promised.) And the movie's second bananas -- like Mindy Sterling as Frau Farbissina, Robert Wagner as Number Two and Verne Troyer as Mini Me -- have the unselfconscious grace of prize cuckoos.

The third entry, "Austin Powers in Goldmember," finds the series at the same place the Bond movies were with the release of "Thunderball" in 1965. Austin has become a pop phenomenon, and a bigness and determination to wow has set in. The parade of A-star cameos (no, I'm not going to spoil the surprises) certifies the series as a show-biz big deal. The cost of this new hugeness is the casualness that was among the chief charms of the first two entries (that's why the movies can be funnier on video than in the theaters). It's the audience's familiar fondness that gets "Goldmember" over its rough spots -- and they're pretty rough. For the first 20 minutes of the movie, everything seems off: The pacing, the story that refuses to settle down and get started, even Dr. Evil's makeup, which looks more like some fan's elaborate Halloween costume replica than the original.

"Goldmember" recovers, miraculously. But bear with me for a few paragraphs while I get the defects out of the way. The most frustrating thing about the movie, which was written by Myers and Michael McCullers, is that it blows one golden opportunity after another. Hearing that Michael Caine had been cast as Austin's father, Nigel Powers, a swinger who has been largely absent throughout his son's life, was enough to give you shivers of delicious anticipation. It's a perfect piece of casting. But Caine has been given next to nothing to do. He drops into the movie now and then, coasting on his considerable charm (and the panache with which he wears double-breasted, pinstripe suits and his old Harry Palmer specs from "The Ipcress File").

And Beyoncé Knowles of Destiny's Child is on hand as Foxxy Cleopatra, a nod to blaxploitation goddesses Tamara Dobson ("Cleopatra Jones") and the great Pam Grier ("Foxy Brown," "Coffy"). Foxxy is plucked from 1975 to the present day to help Austin in his never-ending fight for truth, grooviness and the British way, and the moviemakers never even give her a chance to experience the black pop culture of 2002. Imagine someone steeped in disco and Philly soul waking up in the era of hip-hop (and imagine how she'd be greeted as the hippest of the retro-hip) and you've got a set of comic possibilities that simply don't seem to have occurred to the moviemakers. (Although I think it's simply a sign of how the film tries to cram in too much, it's also a drag -- and slightly discomfiting -- that Austin has almost no sexual byplay with his first black leading lady.)

There's very little material given to Mindy Sterling and Robert Wagner. And there's too much given to Seth Green's Scott Evil; Green's deadpan style doesn't lend itself to the free craziness of the rest of the ensemble. Even Myers, who plays four roles, gets lost in the shuffle himself from time to time. Despite being billed in the title, Austin's new nemesis, Goldmember (played by Myers with a ridiculously funny wienerschnitzel accent and an imaginatively gross personal habit) remains a fitfully amusing supporting character, more a sketch than a fully realized comic creation.

I wanted to get all of those objections out in one go because in the end, they hardly matter. "Goldmember" goes off the rails in all sorts of ways but it never stalls. I've seen much better movies than "Goldmember," but very few that made me laugh so hard for so long. There are extended stretches here that are among the funniest things I've ever seen in a movie. And some of the gags approach the "I can't believe I'm seeing this" quality of the "South Park" movie.

Which is to say that "Goldmember" is a golden shower of toilet humor, which may make the movie a target of the cultural gatekeepers who sniffed disdainfully at "Dumb and Dumber" and "South Park." As for the rest of us -- why pay attention to snobs? Great toilet humor is, of course, about our own ridiculousness and our own mortality, about the way our bodies embarrass us at the most inopportune moments and ultimately betray us. If you're not ready to acknowledge that, like any other kind of humor, it can be done well (Chaucer, the Farrelly brothers) or done badly (almost any comedy involving frat boys), then you're merely using squeamishness and prissiness as the basis of aesthetic judgment.

The toilet gags in "Goldmember" have the liberating gusto that makes you feel like a dirty little kid again. It takes some sort of lowdown genius to combine gusto with the visual intricacy required of good sight gags, and "Goldmember" has several doozies. One sequence takes off from a pet frustration of moviegoers: the impossibility of reading movie subtitles against white backgrounds. And there's a reprise of the shadow-play sequence from "The Spy Who Shagged Me" that goes even further, climaxing in a capper that blasts off like a rocket bound for the vapors.

To give an audience the gift of silliness, the people who made the movie had to first embrace that silliness themselves. "Goldmember" revives some of the oldest gags in the book (like the one about two people disguising themselves as one person via the use of a long overcoat) and executes them as if they were something fresh and snazzy. The spirits are so high that it makes sense, during the first half of the picture, when the movie occasionally breaks out into musical numbers. (They're so good that Myers and Roach should seriously consider making the next entry "Austin Powers: The Musical.")

It's a pity that Knowles only gets to sing one number. In Destiny's Child videos and in her L'Oréal ads, she has never seemed like a real person to me. She's fully alive here, and not just because she's a total stunner. (Kimberly Kimble has come up with a great hair style for Knowles, a huge Afro with lovely golden tints.) Something in the sassiness of the actresses to whom her role pays homage enlivens her. You wish she had better lines and more of a chance to cut loose, but she's confident and sexy and a joy to look at every moment she's on-screen.

The second banana who really gets to shine here is Troyer as Mini Me. In "The Spy Who Shagged Me" his presence was so odd that I couldn't always bring myself to laugh at him. Whether we've had time to get used to him or whether "Goldmember" just provides him with better opportunities (perhaps both), he has the unpredictability of a stray thought made flesh. There's a disjuncture between Mini Me's Tasmanian Devil wildness and his delicate, mincing carriage that Troyer makes the basis of the character's comedy. He makes Mini Me endearing without making him twee; his charm comes from being the movie's wild card.

As for Myers, despite the fact that Goldmember isn't a particularly memorable character, and that Myers has taken Fat Bastard about as far as he can go (I hope this entry marks his last appearance), it's clear that everything in these movies has been filtered through his sensibility. One of the reasons that Austin and even Dr. Evil are so lovable is that they both have a bit of putz in them. They reflect a kid's fantasy of being a cool, suave secret agent and an adult's realization of how silly we look when we try to be cool and suave. Structurally and formally, "Goldmember" is a mess. What saves it is that Myers possesses in spades the thing that's crucial for comedy: an absolute lack of embarrassment and the willingness to go with his gut instinct. Myers presides over the Powers movies the way Austin presides over a bash at his shag pad: They're open to anyone who wants to cut loose and swing. They have a crazy generosity.

Shares