The bad thing about "24 Hour Party People" is that it's blindly ambitious, garishly self-indulgent and reckless with the truth. The good thing is it knows all these things. And the best thing is that it might be a great movie -- certainly as good as almost any other fictional movie about rock 'n' roll, barring a classic like "A Hard Day's Night."

"24 Hour Party People," directed by Michael Winterbottom ("Wonderland," "Welcome to Sarajevo"), is based on real life and is about, in concentric circles of importance, British music, the Manchester music scene, Factory Records, Joy Division and the Happy Mondays, the Hacienda dance club and, finally, Tony Wilson.

The movie starts with Wilson, on a hillside, in the '70s, with a silly haircut and a hang glider. Wilson is a real-life TV reporter and host for Granada Television, a local station in Manchester. He will continue to work on TV, but will also become one of the principal owners of the influential independent label Factory Records -- home to great graphic design and the postpunk quartet Joy Division, which after the death of its lead singer, will become New Order. Plus, he's going to open England's most infamous nightclub. But first, he is going to crash into the hillside.

Wilson is played in "24 Hour Party People" by Steve Coogan, a British comic who in real life plays a fake television show host on, you guessed it, real television. The movie is aware of all these postmodern feedback loops, and will continue to throw them at us at a dizzying pace, culminating in a scene where we actually see the real Tony Wilson playing the producer of the fake Tony Wilson on a phony version of a real show that Wilson hosted. Phew.

"24 Hour Party People" is one of those movies where the main character keeps popping out of the action to talk to the audience. But this movie takes that technique one step further. Here, actors actually step out of character -- not just the action. Sometimes, those actors are playing semifamous musicians, while the self-same semifamous musicians (Howard Devoto of the Buzzcocks and Magazine, Mark E. Smith of the Fall) have bit parts elsewhere in the movie. But it's Tony who breaks out of the action more than anyone else, explaining himself ("I'm being postmodern before postmodern was cool"), or dishing some salacious gossip ("He will go on to sleep with my wife") or delivering an arch line ("William Blake said the road to excess leads to the palace of wisdom. I was headed there in a Jaguar").

That kind of shtick could get old fast, and it's a huge credit to Frank Cottrell Boyce's dense, playful script and Coogan's breezy delivery that it never does. You get the sense that the filmmakers aren't using the technique just to show off or be clever: They're doing it because it captures the sensibility of the period, and because that's supposedly the way semiotics-loving Tony really was. At times, it's dizzying. You're paying attention to a scene, laughing, wondering what really happened and waiting to see if the janitor in the bathroom is going tell you what he really saw 20 years ago, all at the same time. The film is just having too much fun, and the jokes just keep coming, one after another. One of the best laughs is the ongoing disaster of Tony's professional career: He thinks he's a serious journalist; his boss sends him to do a story on a duck who herds sheep.

But wait. If I can be humored to pull my own little Tony, I'd like to point out that you, dear reader, should be wondering what all of this has to do with the music scene in Manchester. And I would say that you make a good point. After all, this is by self-definition a movie about music in Manchester. Tony even says as much: "I am a minor character in my own story."

But that's really not true. "24 Hour Party People" is a movie about Tony Wilson. There's no broad survey of what, to American listeners and viewers, remains a fairly obscure music scene. Yes, pretty much everyone has danced to New Order's "Bizarre Love Triangle" at some high school prom, wedding or class reunion, but who could sing one lick of a James song -- probably Factory's third biggest band? The bed is on fire with passion and love, sure, and then ancient history -- you know, the '60s -- is left untouched. Some of the city's best and most lasting bands from the period when the movie takes place, 1976 to 1992 -- most notably the Smiths and the Stone Roses -- are reduced to single mentions. Neither of them recorded for Factory.

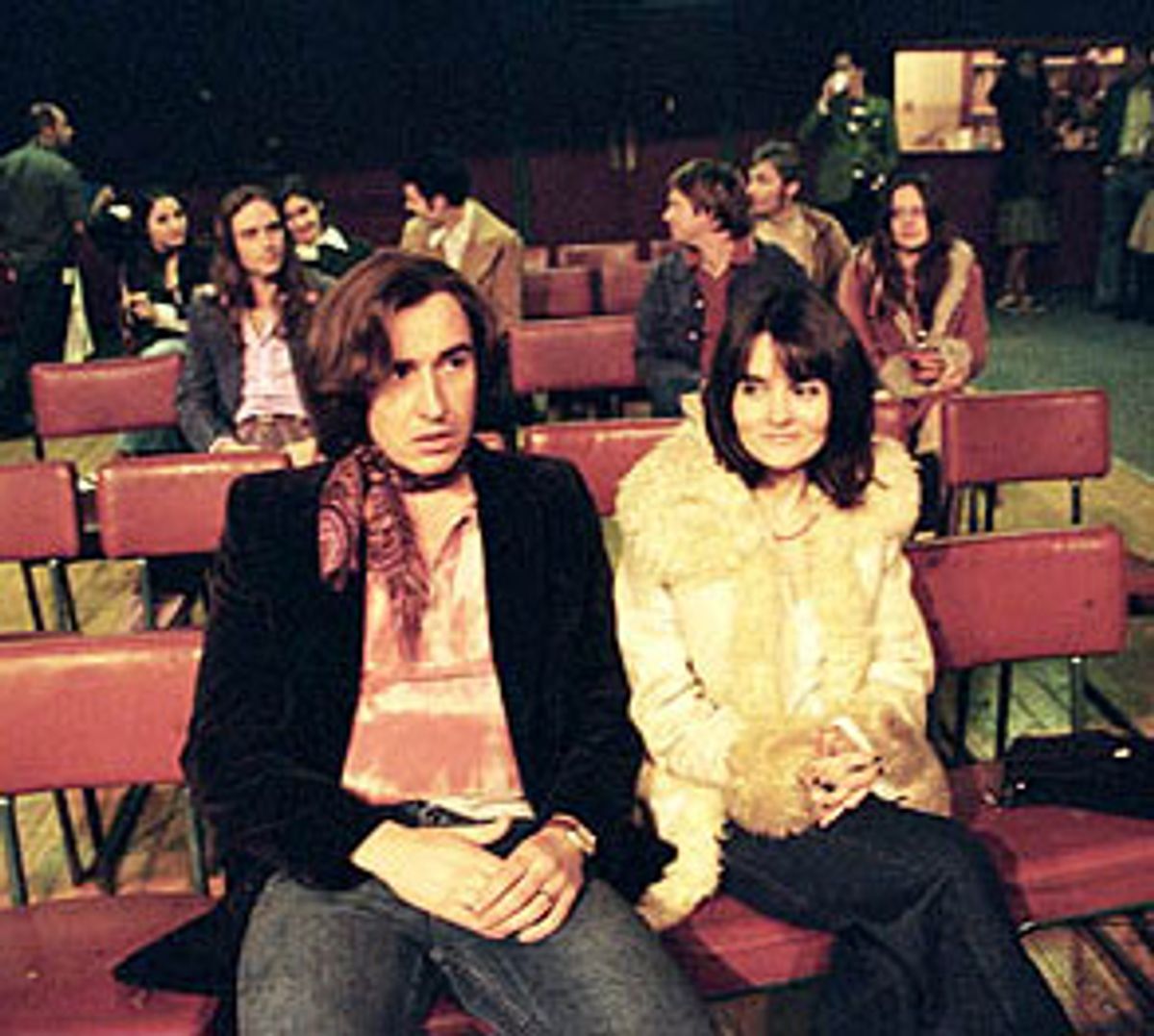

But who wants to watch a movie about all-but-forgotten bands like A Certain Ratio (who are in there) and the Mock Turtles (who are, mercifully, not)? The rise and sputter of Tony Wilson is a better story, and it just so happens that as the founder of Factory, he was at the center of a lot of music. We see Tony at a 1976 Sex Pistols concert in Manchester, and we see actors playing Manchester punk group the Buzzcocks along with the group that would become Joy Division and a bunch of other rockers in a rather bleak room. And then we get an exhilarating look at clips from Tony's rock 'n' roll television show -- mostly London acts.

"24 Hour Party People" is shot on digital video, and the stock is at once a miracle and an annoyance. Anything shot indoors looks pretty good. Anything shot under pink disco lights looks amazing. And anything shot outside, with real light, looks like pixellated garbage. But there are a lot of advantages to DV here. For starters, the camera really moves. You're always on the dance floor with Tony; you swirl around the druggy immersion of the Hacienda; the real archival stuff -- like Sex Pistols footage -- blends right in. (I gotta say, I'm in favor of all these movies made and released in theaters on DV: The stuff gets better -- and cheaper -- all the time. Plus, I see no reason why in five years I shouldn't have access to the resources to make movies just as bad as the ones George Lucas makes.)

Soon after the Pistols gig, Tony starts a club night on a local stage and starts Factory with his friend Alan Erasmus (Lennie James) and Joy Division manager Rob Gretton (Paddy Considine). Tony signs, in his own blood, a contract promising not to rip off his bands. The film handles mythological moments like this with the perfect amount of gravity -- which is to say none. People are drunk, smoking pot and laughing.

Yet Tony, as a character, is always reminding us of the import of certain events. The Sex Pistols show is compared to the Last Supper, for example. He is conscious of making history at every moment. But the film undercuts that by letting Tony be, at once, an enthusiastic narrator and a complete idiot. (He declares tone-deaf Happy Mondays singer Shaun Ryder, played by Danny Cunningham, to be the best poet since Yeats. Sample line: "And all the bad preserves be things that feed me/ I never help or give to the needy/ Come on and see me.")

Factory's first band is Joy Division, and the movie narrows in on the quartet. The actors playing the band members, here and in the rest of the movie, are expertly cast -- particularly Sean Harris as Ian Curtis, all angular intensity and strained neck muscles. Joy Division here represents the beginning of something, and the exuberance of creation, the fun, flailing mess of rock. They're great on stage, they hang around smoking pot, they're willing to try harebrained studio tricks.

Then, out of nowhere if you believe the movie (which we know we shouldn't), Curtis hangs himself. Staying true to their method, director Winterbottom and writer Boyce refuse to treat his death seriously, playing it for black comedy at least three different ways. The weird thing is that it's easy to forgive: You can tell just how much everyone -- and the movie -- misses him.

The Happy Mondays, a shambling lad band, are the center of the second act of the film. (One of their songs is the source of the film's title.) And while the first part was about joy and promise, the second half is about chaos, drugs and incredibly stupid business moves.

I once saw the Happy Mondays live and used to listen to their records all the time, but for the life of me I can't remember why. At best they're a third-tier band in the annals of rock history, notable only for druggy excess, three singles and including in the band a guy whose only job was to gobble Ecstasy and groove to sloppy fake soul-funk.

I'm guessing the Mondays might signify something different in Manchester, and, like so many things that don't make sense to Yanks, it probably has to do with class. Or maybe just drugs. The Mondays revitalize the ailing Hacienda nightclub -- bought in the early '80s and co-owned by Factory and New Order. Before long, acid house, Ecstasy and rock bands that make dance music have turned the club into the No. 1 party scene in the country. Tony tells us something preposterous -- that this was the birthplace of rave culture, more or less -- but by now we're seasoned not to believe him.

Like everyone around him, Tony crashes into his own excess, and the movie grinds down to an ending that is much more rewardingly finite than the end of a music scene ever is. The Hacienda is overrun by drug dealers who bleed it for money, New Order is recording in Ibiza and the Happy Mondays are on crack in Barbados. Tony is about to lose everything, but not in an after-school special kind of way. Because that is the grace of "24 Hour Party People." Instead of a message, we find out something else: that rock 'n' roll, like youth, is fueled by idealism. And that there are different ways to be an idealist.

In the case of Tony Wilson, you can be a wasteful, philandering drug addict who talks too much. And in the end, you'll still manage to treat people right, have a good time and do something meaningful for people. To sell out, but to not sell what's important. To do something big enough for history, and be big enough to let it all go.

Shares