An icy voyage into Sigmund Freud's darker fantasies (by way, perhaps, of the über-intellectual post-Freudian Jacques Lacan, beloved of grad students worldwide), "How I Killed My Father" is the most disturbing and effective thriller I've seen in many moons. Rarely, indeed almost never, is such high-wattage brainpower coupled with pitch-perfect acting and an exquisite, unfakable sense of cinema. French filmmaker Anne Fontaine remains almost unknown on this side of the Atlantic (you might have glimpsed her 1997 feature "Dry Cleaning," if you were quick about it) but believe me, that won't last.

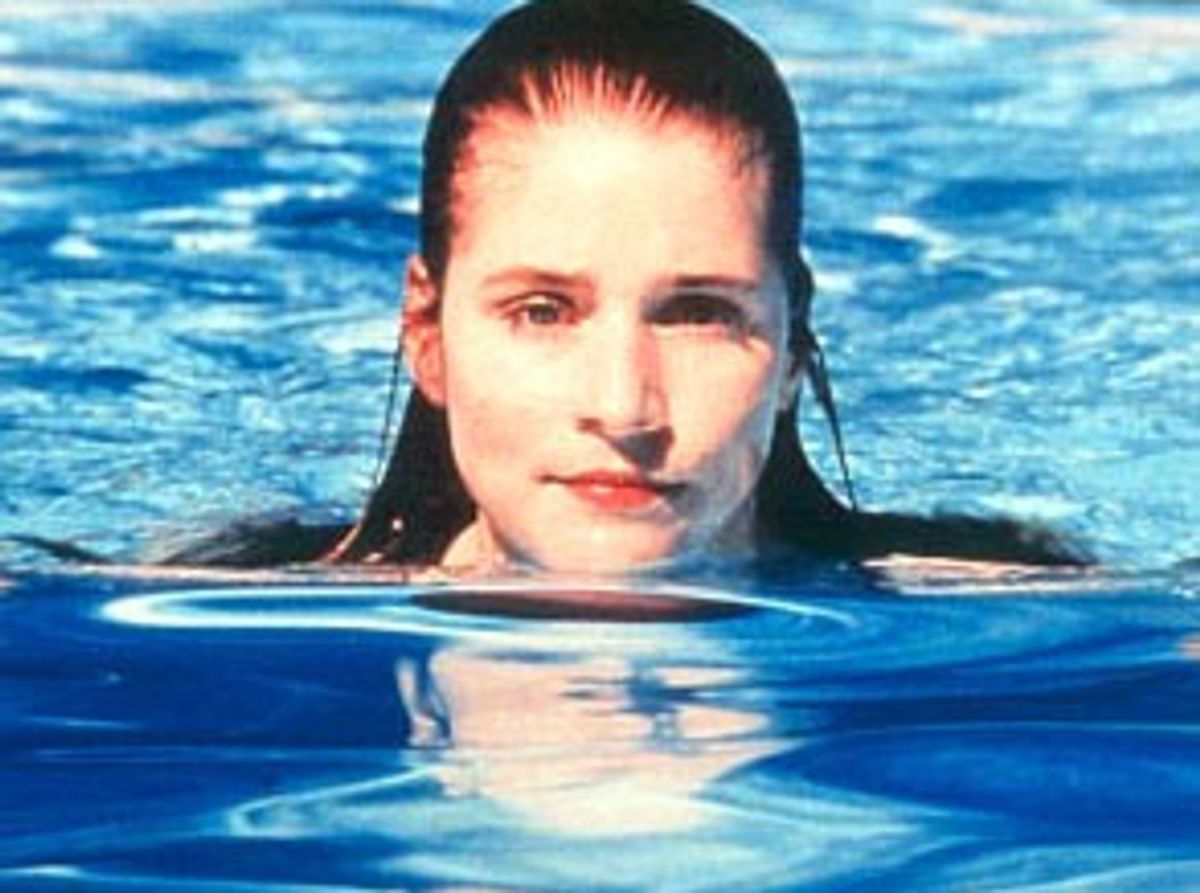

Purely at a pictorial level, "How I Killed My Father" is something close to a masterwork. You could watch it without subtitles, and without knowing a word of French, and you'd not only grasp the basic story but leave the theater haunted by its characters. Fontaine is a former dancer, and her directorial style displays an intuitive command of space and the human body that you can't learn in film school. Jean-Marc Fabre's camera glides between the characters, hesitating just enough to sharpen your senses to a knifepoint, pausing for a troubling extra few seconds on the masklike, almost skeletal face of affluent, 40-ish doctor Jean-Luc (Charles Berling) or the perfect, leggy form of his wife, Isa (Natacha Régnier).

Like "Dry Cleaning," this movie is about a seemingly comfortable bourgeois couple who allow an ambiguous intruder to challenge the basic presumptions of their shared existence and introduce unpredictable discord into their marriage. This time the stranger is an especially intimate one: Jean-Luc's father, Maurice (Michel Bouquet), who fled to Africa 30 years earlier, abandoning Jean-Luc and his younger brother Patrick (Stéphane Guillon) with their mother, who has since died.

Maurice never really explains why he left in the first place or why he has turned up on Jean-Luc and Isa's suburban doorstep; he may be fleeing a regime change in Africa or he may need money, which Jean-Luc has in abundance. But everything about his quiet, stoical father seems to be an attack on Jean-Luc's lifestyle and values. Both men are doctors, but Maurice has been living in Senegal on almost nothing, helping to develop medical clinics for the poor, while Jean-Luc has a lucrative practice in gerontology, trying to lengthen the lives of aging, rich Parisians.

Played masterfully by Bouquet (a French theater actor of tremendous renown who has also appeared in films by François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol and other directors), Maurice can register his apparent judgment of Jean-Luc without uttering so much as a syllable. Shown around Jean-Luc's clinic or his palatial home -- both are in the upscale suburb of Versailles, which of course has powerful symbolic and historical associations -- Maurice will lift an eyebrow, smile his unreadable grimace and fix his eldest son with an unblinking eye. It's enough to drive Jean-Luc insane.

Furthermore, Maurice, with his courtly, almost priestly charm, begins to form friendships with Isa, a shivering if lovely domestic phantom who has convinced herself she can't have children, and with Patrick (who doesn't even remember his father) that threaten to undermine Jean-Luc's patronizing relationships with them. Just when you think Fontaine and co-writer Jacques Fieschi have stacked the deck too much in Maurice's favor, they remind you of what he's done. When a young Senegalese doctor comes to visit the house and sits up late laughing with Maurice, Jean-Luc lurks outside the kitchen window watching, as if he didn't even live there. In Berling's brilliant, implacable performance, you can read his thoughts: My father abandoned me, and found another son.

Perhaps what bothers Jean-Luc the most about Maurice is what bothers all of us about our parents, estranged or not: How much we resemble them. Not only do Maurice and Jean-Luc share a profession, an almost pathological emotional restraint and a taste for drinking milk out of the bottle late at night, they also share fantasies about escaping their lives. When Jean-Luc visits Myriem (Amira Casar), his beautiful Syrian mistress, or goes home with a prostitute on a sudden impulse, he seems most engaged not by the women's bodies but by their families. He pauses to look at Myriem's sleeping child, or to watch the prostitute's elderly parents obliviously eating dinner, as if to remind himself that other modes of existence are possible.

Between the father and son, however, only one of them has actually had the courage or cruelty (or both) to run away. During a late-night conversation when they begin, in their strangled manner, to open up to each other, Maurice recounts how he simply got on a train one day, then caught a plane to Africa to start a new life and try to forget his family. Jean-Luc has only one question: "Does it work? Do you forget?" (Maurice laughs: "The problem is, you do.")

Fontaine is after many things in this film, but social satire isn't one of them. Despite its vicious portrayal of Jean-Luc's hollow existence, "How I Killed My Father" isn't a Francophone version of "American Beauty" or Todd Solondz's "Happiness." The Versailles where Jean-Luc and Isa live isn't a real place, or a parody of one, so much as an abstract psychological space where this primordial Oedipal drama plays out.

"How I Killed My Father" may be too chilly and Gallic a movie to generate a "Mulholland Drive"-scale cult following, but it inhabits a similar realm somewhere between dream and reality, or that moves inexplicably, perhaps, from one to the other. After the opening scene of the film, in fact, it might be reasonable to wonder whether Maurice really visits Jean-Luc's house at all, or if Jean-Luc simply conjures him up because he needs to.

I'm eager not to give too much away about this movie's carefully concocted internal contradictions. Let's just say that Fontaine has studied up on such masters of narrative ambiguity and psychological distress as Ingmar Bergman, Luis Buñuel and Alfred Hitchcock (as well, I suspect, as David Lynch). What's more, she lives up to these examples and has made a film that feels to me like an instant French classic.

Is Maurice really dead, and did Jean-Luc really kill him? Maybe. Sort of. I'm not sure, actually. But that doesn't mean there's no bottom line, no reality, in "How I Killed My Father." As much as this film tries to fight against biology, it finally admits the powerful hold it has over us, a hold that can survive cruelty, abandonment and hatred. "What's between us will always be there, alive or dead," Maurice tells Jean-Luc, in what may or may not be a dream sequence. At the end of a film that sometimes seems relentlessly cold and intellectual comes something like reconciliation, something like love, something alive under the ice.

Shares