There are 8 million stories in the naked city, a number so paralyzing that you can understand why Hollywood keeps filming the same half dozen or so. But one of the pleasures of moviegoing -- or of following any form of art -- is watching the passing parade of variations on the same old themes.

Curtis Hanson's "8 Mile," a not-really-but-kind-of biography of Eminem in which the rapper himself stars, is straightforward, rudimentary, old-fashioned moviemaking, cranking away in the service of a story we've seen over and over again, from "Rebel Without a Cause" to "Saturday Night Fever." But "8 Mile" actually seems to be straining against originality. Hanson, along with screenwriter Scott Silver and Eminem himself, seems more interested in poking a sharpened stick at age-old primal motivations. At once creaky and compelling, "8 Mile" is an early-21st-century meditation on the youthful dream (or necessity) of making yourself heard and getting away, fast, from the roots that threaten to strangle you. The movie takes some of the vitality of '40s youth musicals and retools them for a new generation: "Let's put on a show!" is followed by the even more urgent coda "and then get the hell out of here."

For better or worse -- and maybe, in the end, it doesn't really matter all that much -- "8 Mile" is far less sophisticated than Eminem's music itself: As a performer, Eminem is a master of point of view, an artist who puts himself (and his reputation) at the mercy of the characters he creates. When fancy-pants novelists do that, they win big prizes; when hip-hop artists do it, they're decried as the end of civilization.

No one needs to weep for Eminem, who has sold millions of records and won his share of mainstream music awards. But just because an artist sells millions doesn't mean he's fully understood (if being fully understood is desirable at all). I'm a fan of Eminem's precisely because I can't explain him easily: My inability to get him fully -- as opposed to my approval or disapproval of any of his perceived "messages" -- is what keeps me coming back. He's like a master novelist who writes characters I can neither love nor turn away from: the madman drunk with his own Rolling Stone-conferred power in "Kill You"; the cuckolded husband in "Kim" who turns his pain into a reign of terror. We like to think of art as our friend, but art -- as Shakespeare or Goya or Bacon would have told you -- isn't always kind.

"8 Mile" doesn't even begin to explain Eminem's complexity. If anything, it strips much of it back, making him -- through the character he plays, Jimmy Smith Jr., or "Rabbit," as his friends and family call him -- seem more likable and accessible than he comes off either in interviews or performances. But that's a problem only if you go to "8 Mile" looking for clues about how to interpret Eminem's work (they won't be there). "8 Mile" is much more generic than that -- it's about how our backgrounds always inform us, maybe even more than we care to let on. And it suggests that the only way to break free of the past is to grab it in an octopus grip and stare it down first.

The picture is set in urban Detroit circa 1995 -- the title refers to the area, delineated by 8 Mile Road, that separates the city from the suburbs. Jimmy is a kid in a dead-end metalworking job who's temporarily forced to move back home with his childish, chronically unemployed mother, Stephanie (Kim Basinger), and his adored little sister, Lily (Chloe Greenfield). That home is a trailer park, and Jimmy's none too happy about landing there: He's a remarkably talented rapper, supported by a solid group of friends, although there's a certain amount of insecurity, or maybe just plain shyness, that's holding him back. What he really wants is to land a recording contract and get out on his own. His best hope is to first win a battle in one of the local hip-hop clubs, a competition in which rappers go head-to-head to see who can come up with the cruelest, cleverest put-downs. Jimmy's chief disadvantage is that he's white; outside his circle of friends, he's ridiculed by his mostly black peers. In the movie's opening sequence, we see him taking the stage at a battle, urged on by his friend Future (Mekhi Phifer), only to choke up and fail dismally.

His disgrace and disappointment kick-start the picture: From there, "8 Mile" is all about Jimmy's efforts to find his voice and to use it as a tool, a crowbar to get him out of some pretty dismal circumstances. "8 Mile" trots out plenty of the old conventions -- we see Jimmy driving aimlessly around town in a beat-up car with his buddies, blasting signs, buildings and even police cars with a paint gun; they're the picture of perennially bored youth.

But Hanson understands that those conventions don't have to be tiresome; they can be revitalized every time there's a sea change in youth culture -- in fact, it's about time someone made a picture like this about hip-hop culture. Hanson (director of "L.A. Confidential" and "Wonder Boys") may seem like an odd fit as a director, but he does have a feel for classic modes of storytelling. And he's more interested in people than in topicality; he always takes care to put his characters first. Instead of using them to make blunt statements about poverty or racial tension, he lets the rough textures of their lives unfold before us -- any attendant social issues are simply part of the fabric.

He also seems to get that hip-hop battles didn't spring from nowhere: Jazz fans know they're just another version of cutting contests, onstage competitions in which musicians would ruthlessly out-improvise each other. Hanson slips right into the rhythm of this particular culture, showing how, for Jimmy, hip-hop isn't something you aspire to, but an intensely verbal way of thinking that informs everyday life -- a skill that involves finding the right words for every situation and figuring out, on the fly, how to piece them together for maximum effect.

Hanson captures how freeing and invigorating that process must be, showing Jimmy and Future improvising a rhyme (about their own dead-end lives and Jimmy's mom's stupid boyfriend, among other things) to "Sweet Home Alabama," mimicking Lynyrd Skynyrd's flattened, pure-white Southern accents. Hanson builds up slowly to the picture's best and most thrilling sequence, the final battle, in which Jimmy cuts his opponents to the quick by facing up to the crappiness of his own life and wielding it like a sword. When one guy makes a crack about "Leave It to Beaver," a completely undisguised slam at Jimmy's whiteness, Jimmy turns it against him without batting an eye. He starts out thoughtfully, tugging a little against the beat: "Ward, I think you were a little hard on the Beaver ..." and drives it home from there.

This improvised routine is less a flurry of invective than a finely shaped argument, laced with cultural references that seem to have been grabbed spontaneously from thin air. It's the final argument anyone should ever have to make for hip-hop, done well, as an art form: If you can put the right words together like that and make them swing, you're in a very small minority of human beings on this earth, because it ain't easy.

If "8 Mile" feels old-fashioned but not outmoded, the actors deserve at least some of the credit. Basinger seems to have crawled right into her character: Stephanie's life is all about screwing her good-for-nothing boyfriend (Michael Shannon), going to bingo and complaining about being broke, and not much else, least of all caring for her young daughter. It doesn't matter how beautiful Stephanie is (she looks as if she could be Jimmy's not-much-older sister): At first you wonder how anyone could let her get away with such laziness and irresponsibility. But Basinger pulls a neat trick on us, turning on that milky-sweet Southern accent and reeling us in seductively just when we think we've conveniently written her off.

Phifer plays Future as one of those smart, good-natured, charismatic guys who nevertheless just doesn't have what it takes to become a real success -- it's a small but nicely layered performance. Brittany Murphy, as the girl Jimmy has a thing for, has smudgy, round eyes and hair that flares out like a set of unruly bleached angel wings. Murphy knows how to work those looks: She comes off as both perpetually lost and preternaturally wise, like a Dickensian orphan reimagined by Walter Keane.

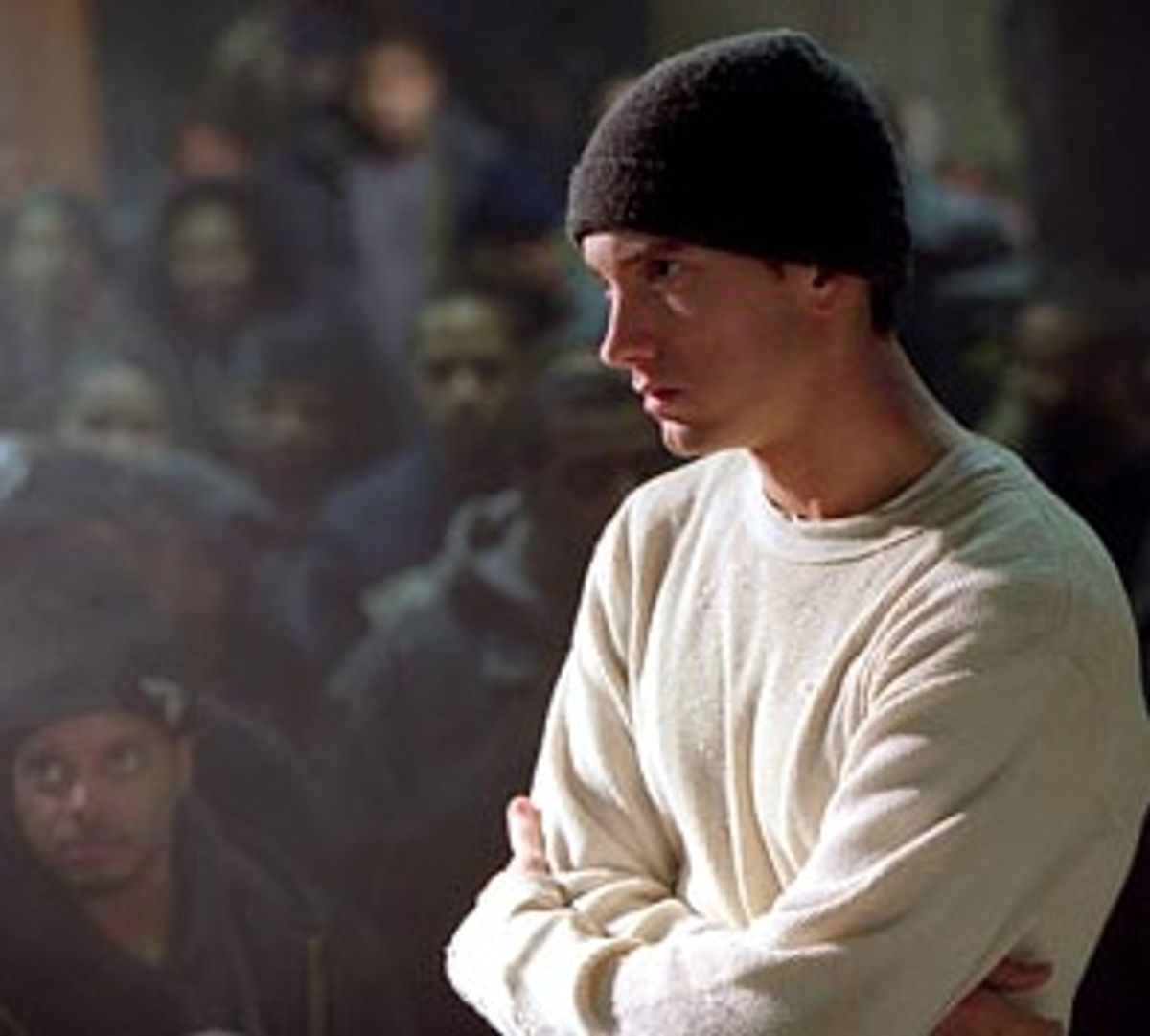

The big question -- Can Eminem act? -- is one that "8 Mile" doesn't answer. But it doesn't have to. There are times when a personality can carry a movie effortlessly, and that's what Eminem does here. He's a purely believable presence. Eminem doesn't reach out toward us. He's veiled and guarded, but even so, he reveals flickers of vulnerability. His slightly protruding eyes give him a potent stare; they're not just a physical characteristic but an explanation for his way of being. It's as if he's taking everything in around him and working overtime to process it as quickly as possible.

Eminem is still a mystery, and "8 Mile" doesn't come close to explaining him. It's probably safe to assume that part of the reason that older, more straitlaced white audiences don't respond to hip-hop is because they feel intimidated by the image -- whether it's real or merely just perceived -- of the angry black male. So what do we make of an angry white one, particularly one like Eminem, who's intimidating because of his sheer intensity? When Jimmy, a scrawny, hunched-over white kid with darting eyes, goes head-to-head in a battle of wits (and wit) with a buffed-up black guy in a muscle T-shirt, there's no question which character is more unnerving. We just don't know what makes Jimmy, or Eminem, tick. But we can hear it, and sometimes it sounds suspiciously like a heartbeat.

Shares