There's uplift all over Denzel Washington's directorial debut, "Antwone Fisher." The movie is competently made, and with cinematography by Philippe Rousselot it looks better than the material deserves. But there's nothing in either the conception or execution to lift it above a TV-movie tear-jerker.

Memoirs have been the literary rage for a while now. "Antwone Fisher" is the first indication that movies may be new territory for people who want to flaunt the stories of their horrendous upbringings. I don't know exactly why it's such a turnoff that the real Antwone Fisher decided to turn his story into a screenplay before writing it as a memoir. Maybe because, for all the egotism that is apparent in too many literary memoirs by people you've never heard of, it's still the work of one person.

To sell your life story as a screenplay is another level of egotism altogether. Basically it means being so confident in the worth of the material that you think a large group of people should pool their talents to realize it on the screen. It's not that Fisher presents himself as flawless, but the whole movie is geared to showing how noble he is, how he had the strength to overcome his abusive childhood. It's designed not to make us say "What a good movie" but "What a good man." And yet, you have to be something of a hustler to convince a star of Washington's stature to choose it for his directing debut.

By the time Fisher was born in Cleveland in the mid-1970s, his father had been shot to death by an ex-girlfriend. His mother gave birth to Antwone in prison and never picked him up when she was released. After a childhood in a foster home where he was both beaten and sexually abused, he spent time in an orphanage, a reform school and on the streets before joining the Navy.

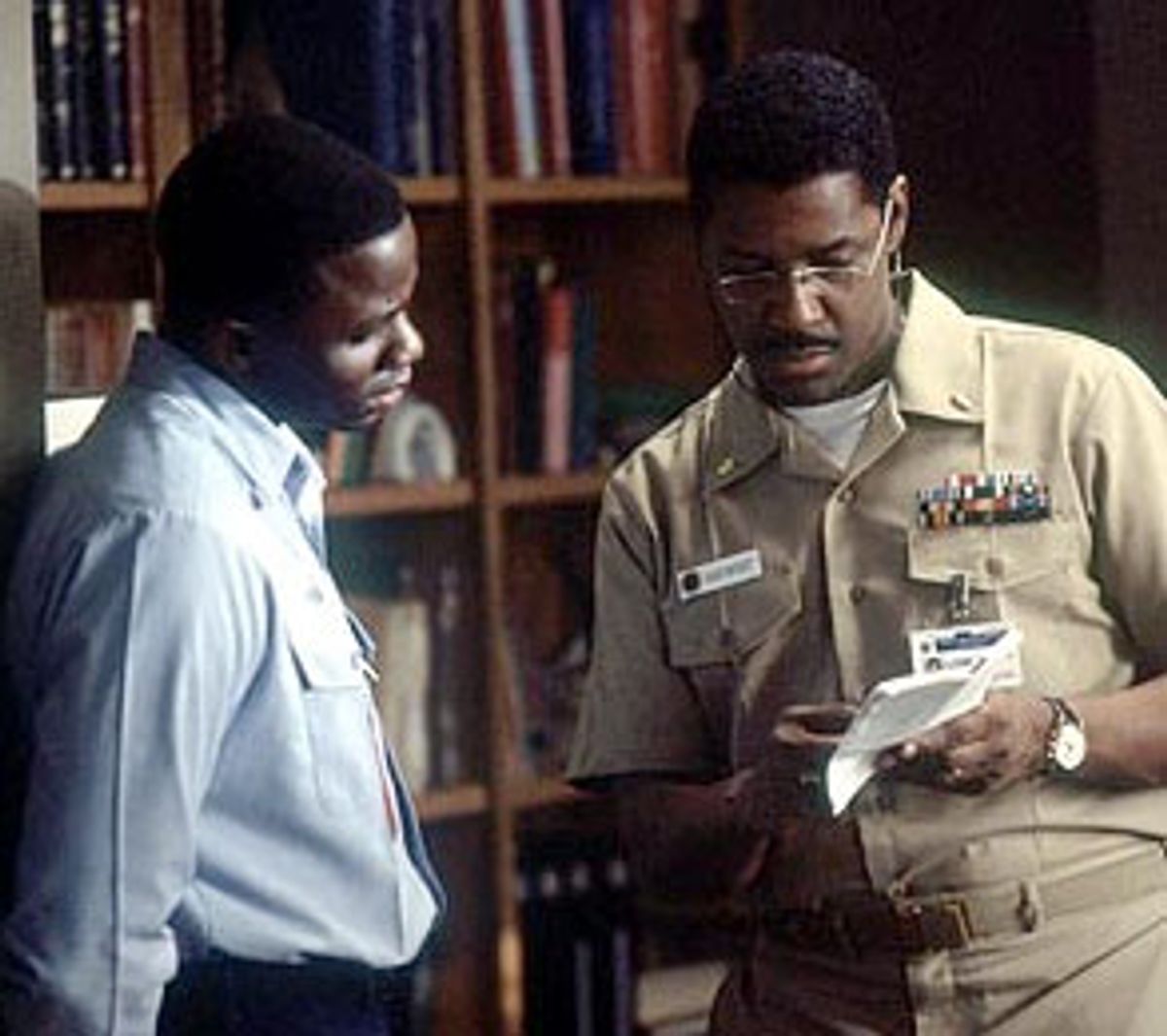

The movie picks up with Antwone as a young sailor who has a problem controlling his anger. Sent to a psychiatrist (played by Washington) he slowly begins opening up, learning to confront the past that has fostered his long-standing rage. Washington's psychiatrist becomes Antwone's substitute father figure, the person who teaches him to drop his guarded resentment, and assures him that he has the strength to face the buried traumas of his childhood. And, this being the kind of movie where everyone learns from everyone else, Antwone's courage persuades Washington's character to own up to his own traumas.

In other words, "Antwone Fisher" is "Ordinary People" with a nice warm black shrink instead of a nice warm Jewish shrink. It's an ode to family and connections and -- above all -- to feeling. And it's just as squishy and sob-inducing as that description makes it sound. Nothing about the movie's psychology makes sense. Antwone grows up being abused by women, but only takes his anger out on men. He's a stammering virgin, and while it makes sense that a sexually abused child would be afraid of sex, the movie never considers the possibility that he might also be sexually brutal, both out of a desire for revenge and because that's what he's learned. It opens with a jaw-dropper of a dream sequence where the young Antwone is surrounded by generations of his ancestors at a family dinner (it looks like the Pilgrims' feast reimagined by Toni Morrison for a long-distance commercial) and ends with that dream being realized.

Probably the movie's most characteristic moment is a montage of black children waiting to be adopted. It encompasses the entire project, which is basically an extended public service announcement ("Hello, I'm Denzel Washington. Won't you please open your heart and home to one of these children?") The aura of worthiness and virtue and spiritual inspiration -- deadly to the movies -- hangs over the whole sodden enterprise. If Oprah hasn't yet dedicated a program to it, just wait.

Washington's acting is better here than his direction. He's the least spontaneous of actors, and without the fire he once showed in movies like "Glory," he's good in roles where he gets to ruminate and work things out in his methodical way. (That's why the idea of him as a bedridden Sherlock Holmes in "The Bone Collector" was so promising, even if the movie was schlock.) So it seems fitting to have him play a psychiatrist. He's fine in the scenes where he's trying to pry open Antwone, but less so when he begins leaking the emotions that spray from the rest of the movie like water from rotting pipes.

It's the less-than-virtuous characters who really stand out here. Like Novella Nelson as Antwone's abusive foster mother, a woman who addresses her charges as "nigger" and expects to be addressed by them as "my dear." Nelson has a quiet, deadly authority. She's an insidious villain, one who masks her sadism in the guise of doing good works. It takes only a few seconds of screen time to understand why the little boys in her charge quake at the sight of her.

If there's any reason to see "Antwone Fisher," it's the five minutes of screen time given to the wonderful actress Viola Davis. Every time I've seen Davis, she has created a character so real that, for a few seconds at least, she stops the movie in its tracks. In "Out of Sight" it was her role as Don Cheadle's neglected wife. In the current "Far From Heaven," it's her performance as Julianne Moore's maid. And in "Solaris," as a doctor on board a space station visited by the crew's dead loved ones, her quiet, devastated face sums up the movie's unnerving menace.

Here, Davis shines in a small appearance as Antwone's mother. When she lays eyes on the son she abandoned years before, she backs away from him as if he were an apparition of past sins risen to haunt her. Davis has the gift of appearing impassive yet conveying a range of emotions zipping back and forth beneath her surface like telegraph signals through an overcrowded wire. In the few minutes she appears onscreen, she makes this engineered moisture-squeezer seem as if it's inhabited by at least one real person.

Shares