There are going to be people who will see "Masked & Anonymous" five times, if not 20, simply because there are hundreds (if not thousands) of people in this world who think, "When it comes to Bob Dylan, why do something just five times when you can do it 20?" They'll search the movie arduously for every in-joke and reference (and there are lots); they'll ponder it, fetishize it, pick it apart as if they were trying to figure out what makes a pocket watch tick.

But my advice is this: See it in one glorious shot, grab as much from it as you can and run like hell.

I say that not because I hated "Masked & Anonymous," but because I loved it. "Masked & Anonymous" -- which opens in New York on Thursday, in Los Angeles on Friday and thereafter in other cities -- is an exhilarating and sometimes puzzling jumble that explores the dangers of power, the nature of Americana and the Bob Dylan myth, among many, many other things. I think the picture is less complicated than it thinks it is -- although perhaps it's complicated in ways that not even its director, Larry Charles (who has worked as a writer and producer on shows like "Seinfeld" and "Mad About You," and directed several episodes of "Curb Your Enthusiasm"), or its star (and, reportedly, its screenwriter), Bob Dylan, would be able to explain. But one of the movie's wonders is the way it recontextualizes the work and legend of Dylan -- even at a time when we may begin wondering if there are any new contexts for Dylan at all. And another is the way it reminds us that Dylan is, first if not foremost, a guy with a sense of humor.

"Masked & Anonymous" is a sideways allegory about an alternative America, a what-if scenario in which our United States -- our republic -- is ruled by a president who looks more like a South American dictator. As is usually the case in countries run by dictators, his image is everywhere, hung with a mix of reverence and contempt. With his dark nail-brush mustache and his cheap white officer's suit, he suggests menace more than benevolence.

But in the world of "Masked & Anonymous," it's often impossible to tell who's good and who's bad. It's not made clear exactly what has happened in this new America, but we get the sense that sometime a while back, a group of people tried to change the world, and their efforts backfired. This is an America torn by civil war. Rebels open fire on country roads. Innocent people are imprisoned simply for valuing their freedom. The government controls the media, which is, incidentally, completely run by black men -- the shows in their lineup have names like "God's Mistake," "It's Alright, Man" and "Terror Tots" -- even though, of course, their power is only symbolic.

In the midst of all this, a sleazy concert promoter named Uncle Sweetheart (John Goodman) and his manipulative, tough-as-bonded-nails colleague, Nina Veronica (Jessica Lange), are trying to organize a benefit for war relief -- or something. In reality, it's their own interests they have at heart. Unable to find a star headliner, they dig up a legendary has-been, an artist that Uncle Sweetheart used to manage (and take advantage of) back in the old days: Jack Fate (Dylan), who has long been imprisoned for an unknown crime.

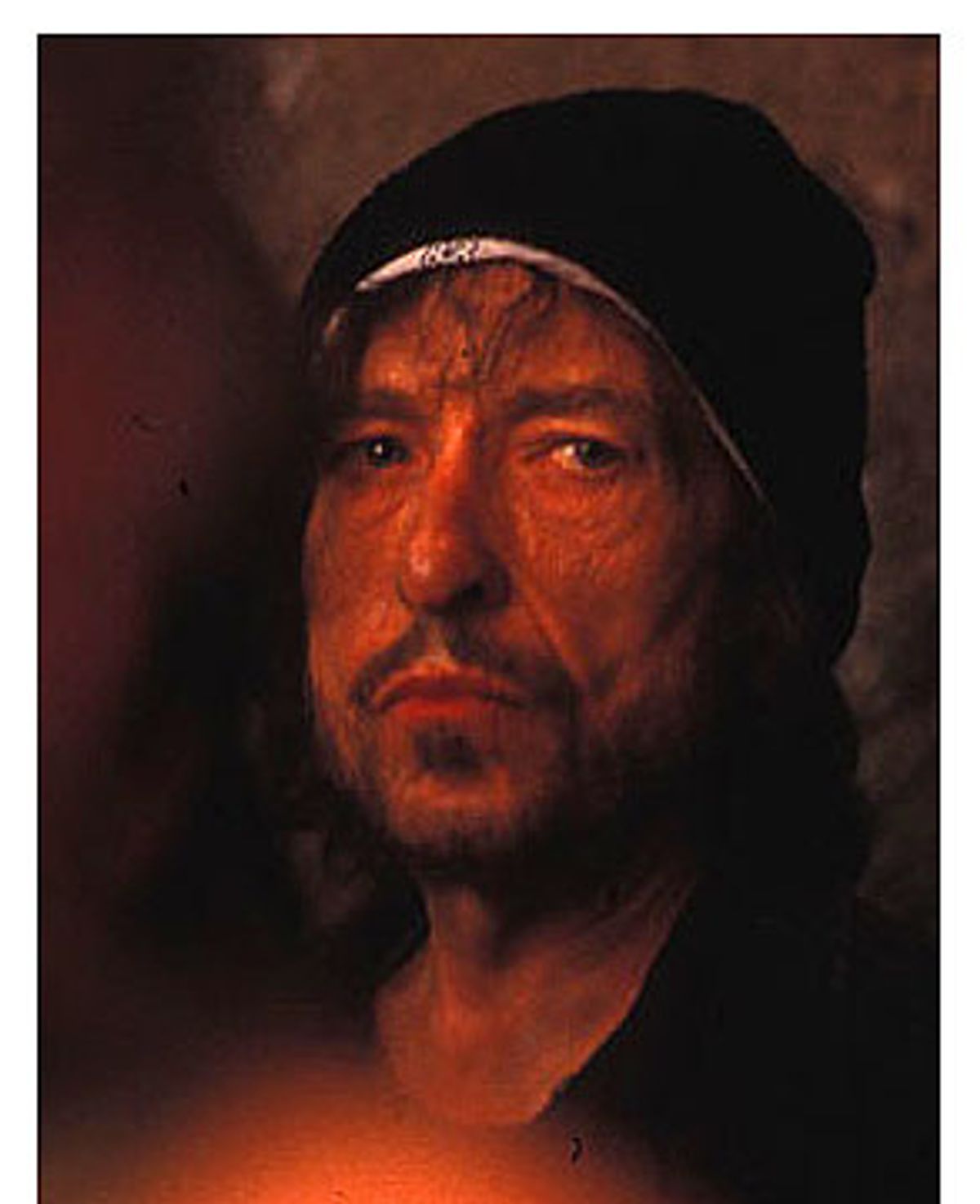

Fate is a troubadour, an artist who, when he's not in jail, lives for the sheer thrill of taking his music on the road, bringing it to the masses. Released from his sentence so he can play the concert, he hits the road in a cowboy hat and a high-buttoned Hank Williams suit, with a guitar in one hand and a garment bag slung over his shoulder -- the uniform and accoutrements of the working musician. He looks dapper and fit in his Douglas Fairbanks mustache, seemingly none the worse for the wear after his stint in the clink. Before springing him, his jailer pronounces, "Keeping people from feeling free is big business," and it's just one of many places in "Masked & Anonymous" where you feel a song coming on -- at least in the metaphorical sense.

In fact, "Masked & Anonymous" is kind of like one long, messy Bob Dylan song -- or, more specifically, a dream version of a Bob Dylan song that folds in just about every motif he's ever written about. The intricacies and not-so-hidden evils of politics, the potency of religion and symbols, hypocrisy, love, betrayal: You name it, "Masked & Anonymous" has it.

Through it all, Dylan's Jack Fate wanders like a grizzled Candide. The great joke of "Masked & Anonymous" is that for once, everything Dylan says is clear and comprehensible; it's everyone else around him who's mad. He takes it all in, sometimes bemused and sometimes amused, and sometimes clearly angry. In one of the movie's funniest sequences, Uncle Sweetheart and Nina Veronica give Fate a list of songs the government has insisted he play (they include "Street Fighting Man" and "Eve of Destruction"). Later, they hand him the words to "Jailhouse Rock," but he brushes them away, obviously miffed beneath his cool demeanor. His explanation (as if he needed one) is like a deadpan sermon. He asks Sweetheart if he knows what cellulose is, and then goes on to explain. "It's in the grass. Cows can digest it, but you can't. And neither can I."

Fate's journey back into the outside world brings him into contact with a misanthropic animal freak (Val Kilmer), a ghost from his daddy's past (Ed Harris), a squeaky-mouse religious obsessive named Pagan Lace (Penelope Cruz, who is, for once, funny instead of merely annoying) and, perhaps the most brilliantly realistic character, an arrogant rock journalist (Jeff Bridges) who doesn't ask questions so much as spew fountains of opinion. The images in "Masked & Anonymous" highlight the ways the stuff of entertainment often becomes legend, and vice versa: There are allusions to circus sideshows, to the legacy of minstrelsy, to the legend of Staggerlee (who, famously, and for reasons no one knows, shot Billy Lyons down cold, even though Lyons pleaded for his life; in the "Masked & Anonymous" version, the murder weapon is Blind Lemon Jefferson's battered, mythic guitar, and it's used as an instrument of truth, justice and honor).

Fate also meets up with an old friend, a bartender, mechanic, guitar tech, you-name-it known as Bobby Cupid (Luke Wilson). Cupid is a version of Fate's younger self -- Wilson plays him, wonderfully, wearing the same pencil-slim curved mustache and even mimicking the phrasing of Dylan's everyday speech. Principled, upstanding, resolutely uncorruptible -- Cupid isn't a purer version of Fate, just a less weary one. His enthusiasm is youthfully fresh, but it's well grounded, too.

Does Cupid represent the old days and the old ways? Is he a reflection of a simpler time -- the '60s, which, somehow, we have come to think of as "simpler" -- when people had ideals and stuck to them? Maybe.

But I don't think "Masked & Anonymous" is so much about the death of idealism as about accepting its limits. For one thing, the songs included in the movie -- nearly all of them Dylan songs, of course, although not all of them are sung by Dylan -- sound bitingly fresh. That's one of Dylan's trademarks, and it will be one of his greatest and most lasting legacies: Every Dylan fan knows that he never sings a song the same way twice. His phrasing rivals that of even the most innovative jazz singer for sheer variety and spontaneity. Sometimes he twists his songs into mysterious phantom shapes. (As Uncle Sweetheart says of Fate, "All of his songs are recognized, even when they're not recognizable.")

"Masked & Anonymous" explores the Dylan legacy in some obvious ways, and in some not so obvious ones. The movie's soundtrack includes an extraordinary reading of "My Back Pages" in Japanese (performed by the Magokoro Brothers) and the equally astonishing "Come Una Pietra Scalciata" (that's "Like a Rolling Stone," rapped in Italian by Articolo 31). And the movie's killer moment comes when a little black girl (played by Tinashe Kachingwe, and she's marvelous), whose mother has taught her every Jack Fate song in existence, steps out to sing an a cappella "The Times They Are A-Changin'."

The obvious point is that Dylan's influence is a web that has been cast over the whole world. But the less obvious one is that even when Dylan sings one of his own songs, he sings it as a cover. It's never just a "version," but a reinvention -- he comes at it from the outside and works his way in, instead of the other way around. In "Masked & Anonymous," Dylan as Fate sings his own songs with his own band (a youthful and vigorous outfit consisting of Larry Campbell, Tony Garnier, George Racile and Charlie Sexton).

But the Dylan songs done by other people and the Dylan songs done by Dylan-as-Fate aren't copies and originals, respectively. They're a type of call-and-response -- a way of magnifying and expanding the material, whether the person singing is the guy who actually wrote the song or an enthusiastic bunch of Japanese musicians. When Dylan performs "Blowin' in the Wind" -- a song I always think I've heard far too many times, until I hear Dylan singing it, again -- he sings as if he's presenting us with something completely new, a little something he scribbled on the back of a matchbook on his way to the gig.

Is there a greater gift than that?

"Masked & Anonymous" is, inadvertently, about how much Dylan has given us. It is also, again inadvertently, about what we've taken away from him. The whole movie is one giant in-joke about Dylan's career and his destiny -- about the person he has become and is becoming, a person who grows increasingly mysterious to us, instead of more comprehensible.

The movie also asks some tougher questions: What happens when you're strangled by your own revolution, and tangled up in your own myth? At the end of "Masked & Anonymous," Dylan walks away from it all, intact, but there's a catch: He walks away in handcuffs, and we watch him go, his image getting smaller and smaller as he drifts away from us. Dylan in handcuffs, Dylan not being "free," Dylan being beaten down by the Man -- those are images right out of a horror show as it might have been conceived by the '60s counterculture, a nightmare vision of the future worse than anything George Orwell (or even just Aldous Huxley) could have imagined.

Handcuffs represent the worst kind of restraint, but are they more constricting than the slipknot of your own legend? Not by a long shot. Dylan-the-icon doesn't need freedom, because we long ago decided that Dylan-the-icon is freedom. Handcuffs mean nothing to an icon -- he can slip out of them like a comic-book superhero. Dylan-the-icon is Plastic Man or Reed Richards, the stuff little kids think about, and pretend to be, in order to conquer their own fears. Grownups cling harder, and more tenaciously, to their superheroes than children do.

That's why I like the image of Dylan walking away in handcuffs. This is not just an aging Dylan, a Dylan with a few little wrinkles, whom we can still claim as "young," just as we like to think of ourselves as young. This is a Dylan who is almost -- almost -- an old man. And he walks with a country gent's gait, as if he's more accepting of that than we are.

The key to that final image, and maybe the key to all of "Masked & Anonymous," lies in a song by Tammy Wynette, who sang from another quadrant of the 1960s -- a place of picket fences and clapboard houses, a place that seemed far away from the wild plains that Dylan roamed. But in Wynette's corner of '60s America, just as in Dylan's, safety was never guaranteed. Idealism is essential to the spirit of any country, at any time. But idealism isn't a guarantee of safety; it doesn't make you invincible. If anything, it turns you into a walking target. Idealism is more dangerous than plutonium.

In those handcuffs, Jack Fate is facing up to the reality of idealism in a way that hundreds of millions of Bob Dylan fans can't. It's a tough job, but someone has to do it. Why shouldn't it be Dylan, playing a fictional character that is, in so many ways, himself? In loving Dylan as much as we do -- because the question always boils down to how we could not love him -- we have rewarded ourselves with the luxury of sitting back and doing all the fancy interpreting and analyzing, while we leave the heavy lifting to him. For God so loved the world that he put his own son in handcuffs, so to speak.

And, as Tammy Wynette sang, after all, he's just a man.

Shares