Woody Allen has a relatively small role in his latest movie, "Anything Else." But figuratively speaking, he's all over it, a one-man marionette maestro rushing from scene to scene, pulling the strings of all the actors and putting his words into every one of their mouths, sometimes without even bothering to disguise his voice. That's not exactly new -- Allen has been doing it for years now, finding young male actors to mold into a suitable stand-in for himself, as well as hunting down scrumptious young actresses against whom he can bounce his knobby, arthritic intellectualism, and, increasingly, his apparent bitterness toward womankind.

But "Anything Else" feels nastier and more pinched than any of the other recent Allen pictures. "Hollywood Ending" may have been tired and forced and aimless, a picture with no reason to exist other than as an affirmation of Allen's existence. But its spirit wasn't as gnarled as that of "Anything Else." This is the sourest of romantic comedies, but it refuses to give in to its own surly nature. Allen keeps using those lovely, crackly jazz recordings as a backdrop -- there's lots of Billie Holiday and some Lester Young here -- as if he actually thinks (or, worse yet, simply wants us to believe) he's keeping true to their wistful romantic spirit. But he has only hijacked them: They have heart, whereas he has none. I know he professes to love this music, but the narrative he hooks it up to threatens to suck it dry.

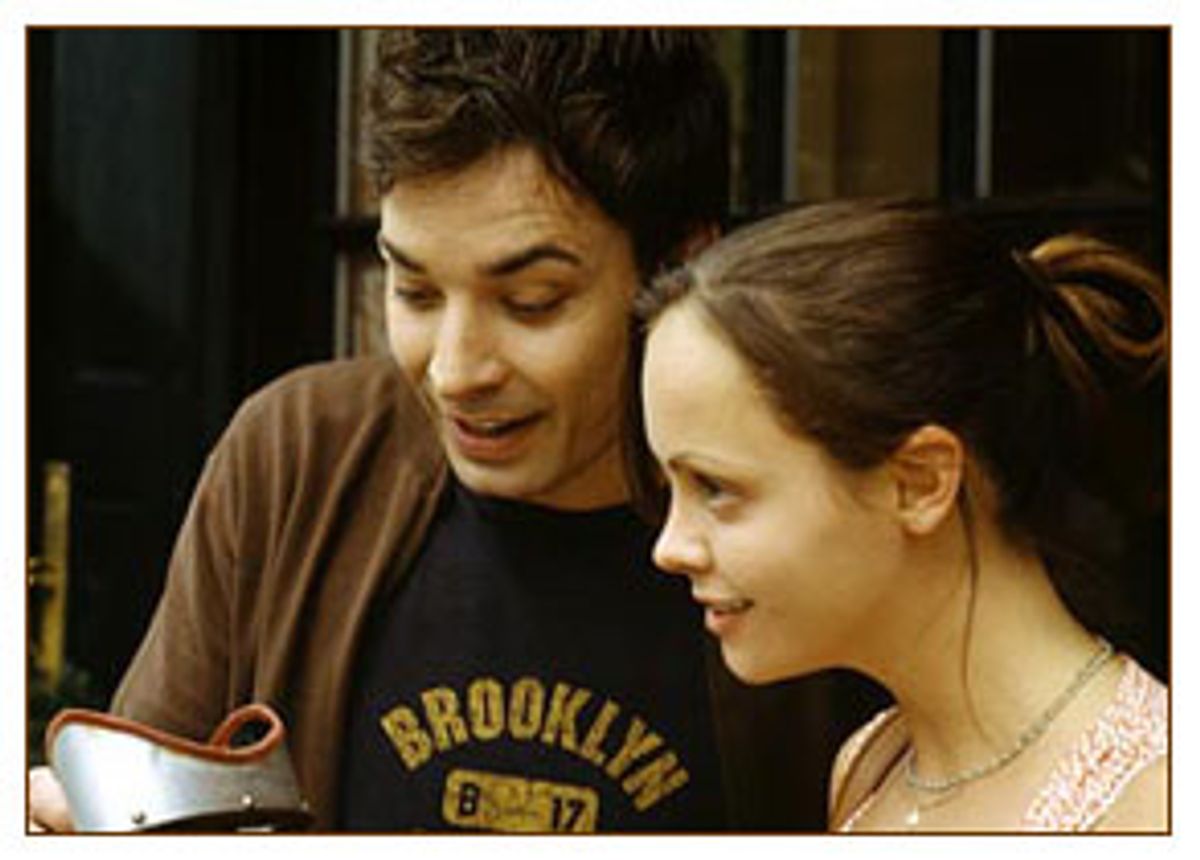

The star-crossed sapsuckers at the center of this love story are Jerry Falk (Jason Biggs), an aspiring comedy writer, and his dizzily manipulative girlfriend, Amanda (Christina Ricci). Jerry and Amanda are presented to us as his-and-hers neurotics, but their obsessive patterns are very different. Jerry is a neutered puppy, bumbling and good-natured and eager to please. Amanda is the voluptuous, seemingly helpless coquette who's really a Kali of insecurity: It may seem that she's only melting and softening the world with the charm of her giant saucer eyes, but she's really frying it.

Amanda is the kind of woman who, after moving in with Jerry, completely loses interest in sleeping with him. He begs and pleads and cajoles, but no dice. He confides his problems to his new friend, David Dobel (Allen), a schoolteacher and sometime comedy writer -- as well as a gun-happy paranoid lunatic -- who gives him all kinds of allegedly helpful advice that's really just noodly strings of nonsense, usually involving cab drivers and Camus and topped off with a capper like, "You know, it's like anything else -- think about that."

The notion of Allen as this particular kind of kook is admittedly funny, and it suits him in a roundabout way. Some people grow to look kinder as they age; Allen, his eyes looking smaller than ever behind giant glasses, just looks meaner. I wanted to laugh when Dobel's temper boils over and he grabs a tire iron and goes at the car of a couple of boneheaded thugs who took his parking space. (He has to swing his scrawny arms three times just to bash a single headlight.)

But as much as I knew the scene should have been funny, I couldn't laugh -- maybe because, even though Allen has built a career out of being the charming, self-involved loser who wouldn't hurt a fly, his movies increasingly seem to be made by a man who really does hate the world and most of the people in it, including himself. In that light, the flip-out with the tire iron doesn't seem so funny.

Twenty years ago, I wouldn't have guessed that's where Allen was headed: His comedies may have had their sharp edges, but Allen's anger and frustration seemed to spring from genuine confusion. Now he's just a churlish wisenheimer, and he seems to think it's cute.

He's written Jerry as a dream version of his younger self -- I say dream version because in his movies the young Allen was never as guileless or as sweet as Jerry is. He was also a lot more interesting. Allen has given Jerry plenty of neuroses, but they're furry, cuddly, boring ones: He lies on his analyst's couch and wonders why the guy never responds to his heartfelt outpourings with anything other than a bland question. ("And how does that make you feel?") It's as if Allen wants to hog all the good neuroses for himself, clutching them to the bosom of his younger self: Even though he's written a character who's supposedly a stand-in for himself, he doesn't want that character to be more engaging or complex than he ever was.

For that reason, and maybe some others, Biggs flounders in the role. Biggs can be a charming actor, as in the original "American Pie." But he's best when he keeps it simple, when he plays the kind of earnest, well-intentioned guy that he looks to be. Allen directs nearly all his male leads to speak in his own rhythms, and Biggs can't handle them. When Dobel urges him to ditch his two-bit agent (played with perfunctory weariness by Danny DeVito), Jerry intones, "He's my cross to bear," and the line hits the pavement with a thud. You can hear the way the 30-year-old Allen would have slung the line perfectly, the way a killer short-order cook flips a flapjack. Allen doesn't direct actors; he coaches them in Woodyness. I often wonder if he doesn't subconsciously will them to flop, if only to stroke his own vanity, to reassure himself that he can never really be replaced.

Yet Christina Ricci's Amanda gets it much worse. Ricci has an angel's face and a wowser of a figure: Her curves make you long for the days when seamed stockings were meant for everyday wear. But Allen has written a part for this capable actress that's really no part at all. Amanda's shortcomings are played for rueful laughs at first. We're supposed to laugh at the way she crushes poor Jerry's hopes for a romantic anniversary dinner by announcing that she's already eaten. She then launches into a litany of exactly what she ate, which starts with a whole cheesecake and wraps up with a carton of eggs. Then she laments, in that way some women do to insure that their companion's attention doesn't drift from them for one second, that she's fat.

By the time Amanda announces to Jerry that she's slept with another guy, just to make sure she's still capable of having an orgasm (she is -- "Isn't that good news?" she asks brightly), she's about as cute as a cannonball. Amanda isn't a complex character, with flaws and good qualities that mingle restlessly in our minds: She's an extreme one, one that Allen pretends we're supposed to like, at least on some level (perhaps just a sexual one). But Allen has nothing but contempt for her. It's as if he's saying, "This is the sort of girl we fall for, and we'll do anything for them, and just look what they do to us!" -- without acknowledging that men's own cracked judgment ever has anything to do with it. Ricci's performance is both flat and imploring; she's constantly begging us for something, but damned if we know what it is. All we know is that the insistent tugging is wearying, and we, unlike Jerry, want to get away from her as soon as we can.

But Jerry keeps plugging, because that suits Allen's point: Just look what we'll do for these undeserving women! Jerry even acquiesces when Amanda's mother, Paula (Stockard Channing, who makes the best of a puny, one-note role that's far beneath her talents), moves into their tiny apartment. Paula is the hardened nightmare version of her daughter, times 12 -- she can no longer speak; she only barks. The apple, Allen seems to be telling us with a waggling of a finger, doesn't fall very far from the tree -- and you can always be sure there's a worm inside.

The characters in "Anything Else" don't talk the way anyone really does in New York; they talk like people who think they're in a Woody Allen movie. At one time Allen captured the rhythms of the city better than any other filmmaker, but he's lost touch with its contrapuntal melodies. It's as if he's trying to re-orchestrate those rhythms, to give them to us as he thinks they should sound instead of as they are. I've begun to wonder if he still loves New York at all.

Does he really love anything? I've given up wondering about that, because the answer seems to be no. "Anything Else" isn't just the latest Woody Allen movie; it's also the smallest. His pictures seem to be getting tinier and tinier, and after you've seen them they leave nothing but a tinny echo and a bad taste. "Anything Else" is misanthropy writ small. Allen is too stingy to be generous even with his contempt.

Shares