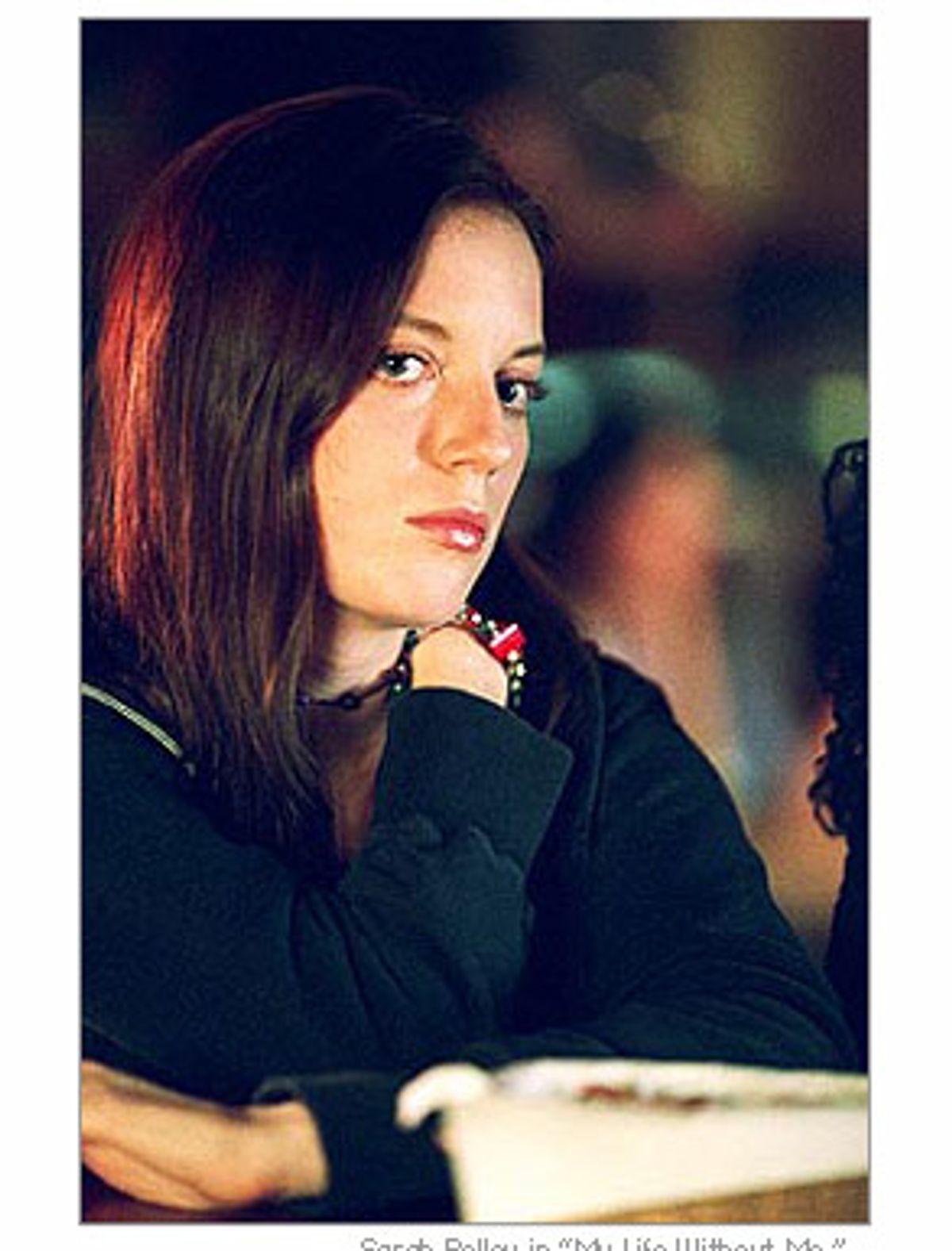

Sarah Polley is such an unforced, unfussy, unaffected actress that nearly everything she does on-screen feels both believable and sympathetic. Playing a young mother given two months to live after a diagnosis of ovarian cancer in "My Life Without Me," Polley avoids the temptations to give in to melodrama that other actors would have fallen for. With the exception of one badly written speech that nobody could pull off, Polley doesn't work to form a lump in our throats. In the scene where she gets the terminal diagnosis, you see her lower lip tremble with the beginning of a sob and just as abruptly see her choke it back. In giving this young woman her dignity, Polley affords the audience theirs as well. Any tears spilled over Polley's performance are earned, honestly.

Her performance is all the more remarkable because "My Life Without Me" is so bad, and nobody connected with it appears to have noticed that Polley's character, Ann, is something of a monster.

According to writer-director Isabel Coixet, in the Nanci Kinkaid story on which "My Life Without Me" is based (from the book "Pretending the Bed Is a Raft") the young woman tells everyone that she is dying. In the director's statement among the movie's production notes, Coixet says she wondered, "What would happen if [she] didn't tell anyone ... if she discovered that the greatest gift she could ever do [sic] to her family, especially to her kids, was not to burden them with the weight of her future death?"

That's not a bad dramatic idea, and Polley makes it work. It's understandable that Ann decides she doesn't want to spend her last weeks in a hospital, drugged to the gills and going through a battery of tests and procedures. It's courageous, though, that she doesn't want her husband, Don (Scott Speedman, who's very sweet in a thankless role), or her two young daughters to have that as their last memories of her. The trouble is that instead of being about a woman who wants to fade gracefully away from the people she loves so they can get on with their lives, the film becomes about someone who is egocentric enough to ensure that they never forget her.

Polley's best, most affecting scene is the one where she pulls into an empty parking lot late at night and tape-records messages for her daughters for every one of their birthdays until the age of 18. As with everything else here, her performance is held beautifully in check. She puts just a slight, fleeting quaver into her voice, betraying her sadness but determined to keep it bright and happy for her kids' sake. This is also the most appalling scene in the movie.

You can understand Ann leaving a message for her daughters telling them to be strong and telling them that she loves them, or a message for when they come of age trying to impart some of her experience to them. But if her choice not to tell them she's going to die comes from a desire not to burden them, then imagine how these little girls (who are 6 and 4 in the movie's present tense) are going to feel at 8 or 10, knowing that every birthday means that along with greeting cards the postman is bringing a tape from their dead mother telling them not to be sad. (Ann arranges with her doctor to mail out the tapes each year.) Is this her idea of letting them get on with their lives? Had Philip Roth conceived of a ploy like this it might have provided Alexander Portnoy with the ultimate Jewish-mother joke: "Hello, darling, this is your mother. I'm still dead but I want you should have a happy birthday."

Ann got pregnant at 17 and married Don, her high-school sweetheart. Now, at 23 with two daughters, they live in a trailer in her mother's backyard and he is the only man she's ever slept with. Understandably, she wants to know what it's like to make love with a different man before she dies. Only a prude would begrudge Ann a taste of some sexual variety. But instead of finding a guy (or even a few different guys) for a pleasant one-night stand, she decides that one of the things she wants to do before she dies is to "make someone fall in love with me."

Lee (Mark Ruffalo) is the poor schlemiel whose heart she tramples on in order to fulfill that narcissistic wish. Lee is a bookish loner who's traveled the world and settled in Ann's small Canadian town, seemingly nursing a broken heart. There's nothing original about the conception of the character -- it's what a moonstruck adolescent might come up with -- and nothing particularly charming about Ruffalo's mannered performance (he seems to be apologizing for every line he speaks). Yet you can't help but feel for this guy who has his infatuation encouraged, only to be abandoned. Then, a few weeks later, he finds out the woman he fell in love with is dead.

Coixet has given Ann a passel of blue-collar clichés: a contentious relationship with her mother (Deborah Harry), whose life has been a series of disappointments, and a nonexistent one with her father (Alfred Molina, moving in his one scene), who's been in prison for 10 years. To her credit, though, she doesn't see Ann and Don's life as one of thwarted potential and crushed dreams. They genuinely love each other and their two daughters aren't driven apart by the tough times they face (Don, a construction worker, is hunting for a job). It's refreshing for a movie about blue-collar life to portray it as something other than dingy and soul-killing.

Whey then, is the movie so determinedly drab? If your only experience of Canada is Canadian films and the short stories of, say, Alice Munro, you could be forgiven for wondering if anyone in Canada ever has a good day or if the sun ever shines there. I don't know if "My Life Without Me" was shot on digital video but it might as well have been. It's just as dull and washed-out, and just as much of an insult to the audience.

In one scene, Deborah Harry sits alone in her house late at night crying over a Joan Crawford movie on the late show. We're meant to see that the clichés of old, soapy movies are her outlet for all the things she wanted that she never got. But "My Life Without Me" is a new-style soapy movie. Essentially, it's the old TV-movie weeper "Sunshine," about a pretty and dying young hippie mom, done up in indie dinge.

Anyone who's ever spent any time around people who are sick or dying knows that the seriously ill can be unreasonable, even selfish. And while it may be understandable given their circumstances, it doesn't diminish the hurt they can inflict on the people closest to them. Impending death can cause buried resentments and anger to come to the fore, sometimes viciously. Had Coixet been willing to explore that, she might have had a thorny, potent movie. But "My Life Without Me" falls squarely into the Hollywood tradition of being unable to portray the dying as anything but noble and self-sacrificing. Coixet ignores the disparity between what Ann says she wants to do -- find a way to keep her loved ones from the pain of losing her as long as possible and ease them into life without her -- and what she does, making sure that reminders of her death will haunt them for years afterward.

There's something creepy and unacknowledged about the way Ann manipulates everyone around her. She invites her neighbor, a nurse played by Leonor Watlin, for dinner in hopes of setting her up with Don and providing her kids with a mother. Watlin is appealing enough, but she has to deliver an impossible monologue about working as a pediatric nurse and sitting with two dying conjoined twins. (Apparently nobody told Coixet that babies are not just taken out of incubators and left to die, and nobody has told her that conjoined twins are always the same sex.) It's a showstopper, the kind of gruesome tear-jerker that was parodied by Phoebe Cates' famous monologue in "Gremlins." Coixet presents it straight.

It's easy to imagine, 50 years from now, somebody weeping over "My Life Without Me" on TV late one night the way Deborah Harry weeps over that Joan Crawford picture. It's all done up in washed-out indie integrity, with hand-held camera movements that make no sense (in one scene, in the trailer's dining nook, the camera seems to be shooting from beneath Polley's armpit). And it has its streaks of patented indie eccentricity, trashing two good actresses, Maria de Medeiros as a hairdresser who worships Milli Vanilli, and Amanda Plummer as Ann's co-worker. (Indie filmmakers don't know what to do with an actress of Plummer's singular gifts, except cast her as a freak.)

For all that "My Life Without Me" is essentially the same old Hollywood eyewash about the noble mother suffering silently for the sake of her children, it's about as phony and manipulative as a movie could be. That Polley seems true every second is maybe the strongest testament yet to her acting. It's exasperating that this movie doesn't have the courage to go places where its actress plainly has the guts to follow.

Shares