There's an old showbiz maxim that you should always beware of sharing the stage with children and animals. When it comes to a movie like "School of Rock," one should probably extend that law to include critics. I could stand here on the sidelines in a tweed jacket and bifocals, complaining that this probably isn't a good movie and might not even be a movie at all, in some technical, Platonic sense. It's more like a haphazard "Saturday Night Live" sketch blown up to 90 minutes; its storytelling is nonsense and it traffics in borderline-offensive stereotypes and caricatures in almost every scene. Or I could just tell you that none of that matters to even a microscopic degree, because this is a movie in which Jack Black and a bunch of fifth-graders play AC/DC songs, and resistance is futile.

So throw off your waistcoat and your prep-school tie, toss your horn-rim specs to the crowd, raise your Goblet of Rock to the gods and start doing the Swim and/or the Mashed Potato. Because in its cornball "Let's put on a show!" crudeness, its Cuisinart collapsing of rock history, and its reduction of the ambiguous, libidinal revolt led by Elvis and Mick and Johnny Rotten and Kurt Cobain to the level of pampered middle-school posturing, "School of Rock" is a clever and sometimes a beautiful thing.

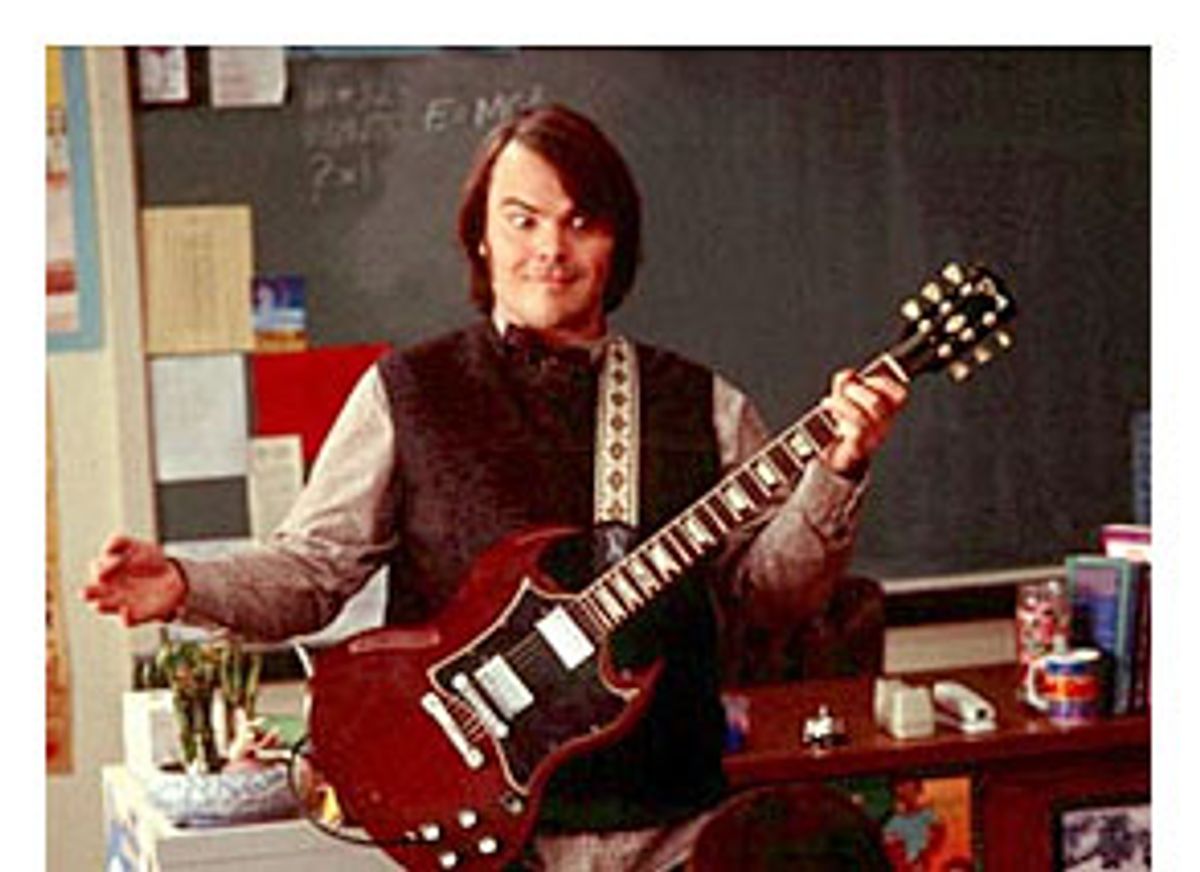

There's a ridiculous plot to explain how dead-end rock guitarist Dewey Finn (Black), in a last-ditch effort to make the rent, impersonates a substitute teacher and winds up in charge of a fifth-grade classroom at his nameless state's most exclusive private school. (The Gothic exteriors are actually those of Wagner College, on New York's Staten Island.) But everything that happens in "School of Rock" has only two goals. The first is about the sheer physical and visceral delight of seeing the amped-up Black with a roomful of 10- and 11-year-olds, as he tries to teach them not merely to play "Iron Man" and "Smoke on the Water" but also to feel them, in something like the overly intense, almost metaphysical way he does.

But the second, subtler point of "School of Rock" is actually a lot more interesting. Black certainly isn't regarded as a delicate performer (although he was wonderful in "High Fidelity"), but his portrayal of Dewey walks the knife-edge of satire without ever slipping into mean-spirited mockery. Dewey, as at least one other critic has observed, seems to be trapped in his own personal 1986. (As if recognizing this, there's nothing on the soundtrack more recent than early Metallica, and otherwise it's a highly enjoyable '60s-to-'80s cross section, ranging from the Who to Bowie to the Ramones.)

If it weren't for the occasional cellphones and Christina Aguilera references, I would suspect this movie was actually set in 1986. Of course Dewey is deliberately distant from reality -- but honestly, how many guys like this are left, even in the slummy $600 apartments of downscale urban America? He's almost literally a dinosaur of rock, a wannabe guitar god who's now somewhere north of 30 with no job, no girlfriend and no furniture and is just beginning to notice that his dreams of stardom have grown tired and pathetic, at least in the eyes of the world.

But guys like Dewey are surely no strangers to verging-on-middle-age bohemians like director Richard Linklater ("Dazed and Confused," "Waking Life") and screenwriter Mike White ("The Good Girl," "Chuck & Buck"), nor for that matter to Black himself, who plays in the sort-of-joke band Tenacious D when he's not acting. The portrait of Dewey they create is complicated and affectionate; if he's a pathetic figure, he's pathetic in the truest, most old-fashioned sense of that word. He's deeply flawed, self-involved and childish, but he's also noble. He believes profoundly in something bigger than himself, and if that something is capital-R Led Zep-era Rock in its most self-important incarnation, well, as Nietzsche once observed, we have killed God and we only have Rock to replace him. (Perhaps I am paraphrasing.)

In other contexts, Black's wild-man shtick can get old fast; I found his out-of-focus Michael Jackson riff at this year's Grammys ceremony teeth-grindingly bad. But he was anointed by God (or by Jimmy Page, since God is dead) to play Dewey, and he makes the hackneyed notion that this washed-up impostor has something to teach these kids that they wouldn't otherwise learn -- such as the definition of "sticking it to the Man" -- come gleefully alive. I'm not going to spoil the movie's gags and musical numbers for you, but Dewey's song "In the End of Time," a pompous faux-Zeppelin number that purports to be mythological in nature (but turns out to be about getting kicked out of his last band), is a deathless classic.

Dewey's roster of grade-schoolers -- all of whom genuinely play their instruments -- is too full of delights to enumerate, but my favorites are the young classical pianist Lawrence (Robert Tsai), who must be convinced of his innate ability to rock, and somber bass player Katie (Rebecca Brown, who's ready to replace Kim Gordon if she ever decides to quit Sonic Youth). Joan Cusack does about the best anybody could with the role of the school's monumentally uptight principal, whose gawky, angular repression doesn't quite conceal the inner Stevie Nicks that longs to get out. Screenwriter White -- who's always good in the roles he writes for himself -- plays Dewey's nebbishy roommate, who's relentlessly hounded by his yuppie-nightmare girlfriend (Sarah Silverman) into persecuting Dewey for the rent. (Dewey protests, "Sell my guitars? Would you tell Picasso to sell his guitars?")

Those three adult characters all feel like afterthoughts, stick figures who don't have enough to occupy them, and in a movie that's fundamentally this much fun that's too bad. But it's clear that Linklater's attention was absorbed by the dizzying, dazzling, half-improvised classroom scenes and, of course, once you have been taught the Gospel of Rock adult life matters less and less. Perhaps when everyone reconvenes for "Back to School of Rock" the result will be a mannered, sensitive and grown-up motion picture. With fog machines and drum solos.

Shares