In the world of Quebecois filmmaker Denys Arcand, baby-boomer intellectuals are fascinating people, particularly to themselves. In fact, they're their own best audience. Arcand's intellectuals no longer make love like they used to in the '60s: Sadly, after having so proudly invented the sexual revolution, they must now leave the florid, sordid pleasures of the flesh to their younger kits, children of the '80s and '90s who, it seems, just don't have the same gusto, the same joie de vivre.

But even though the old folks have hung up their lovemaking shoes for good, they talk about the old days -- oh, how they talk! The women, flushed with Chaucerian boldness, speak of how many roosters they serviced back in the day, rolling their eyes saucily at the memory of such ribald pleasures. The men, now stooped and worn, spring to life temporarily, invigorated by the memory of what it was like to have such attentions lavished upon them. But because we're talking about serious thinkers here, bigger topics also flip-flop on the discussion table: the decline of Catholicism and with it, the death of faith; the way the "isms" (communism, feminism) were tried on so freely in the old days, like party clothes, notions to be toyed with and either adopted as permanent styles or discarded. Those old '60s academic types, with all that freewheelin' lovin' and book-learnin', sure knew how to live. And now, they're aging and, yes, dying.

Are all '60s-era intellectuals this tiresome in real life? Not by a long shot. Why, then, should we want to watch these particular ones on-screen? "The Barbarian Invasions" is Arcand's follow-up to his much lauded 1986 "The Decline of the American Empire," in which a group of middle-aged French-Canadian friends dissect their marriages and love affairs in between dropping anvil-size hints about how intelligent and well-educated they are. If you liked "The Decline of the American Empire," you'll probably enjoy "The Barbarian Invasions," and don't let me steer you away. It features many of the same characters we met in the earlier picture, now some 15 years older. One of those characters, Rémy (Rémy Girard), is gravely ill and must grapple with the reality of his impending death.

As I see it, though, the characters may be older, but they still haven't grown up. In fact, they've become more irksome and intolerable. Rémy, a chronically philandering history professor, lies ill in his hospital bed, which is crammed into a chaotic, poorly run Canadian hospital. Although his wife, Louise (Dorothée Berryman), became frustrated by his constant womanizing and booted him out of the house long ago, she has swooped loyally to his side and summoned the couple's son, Sébastien (Stéphane Rousseau), from London, where he holds a highfalutin finance job.

Sébastien and Rémy have never gotten along, and it's understood that Sébastien has taken great pains to build a life as different from his father's as possible: He's devoted to one woman, a buxom looker named Gaelle (Marina Hands), who is nonetheless too crisply professional (she's a dealer of high-end art) to seem particularly sexual. Eschewing a life of the mind (or perhaps just turned off by his dad's blowhard philosophizing), Sébastien has opted instead to make big bucks. When he returns home to help his father through his illness, the two clash. (Rémy also has a daughter, who lives on the high seas, sailing yachts around the world, and connects with him only via satellite.) Yet Sébastien takes it upon himself to summon his father's old friends from various spots around the world, as well as to do whatever he can to ease Rémy's physical suffering. To that end, he contacts Nathalie (Marie-Josée Croze), the daughter of one of Rémy's old mistresses and one of his own childhood friends, who knows the ins and outs of scoring illegal drugs.

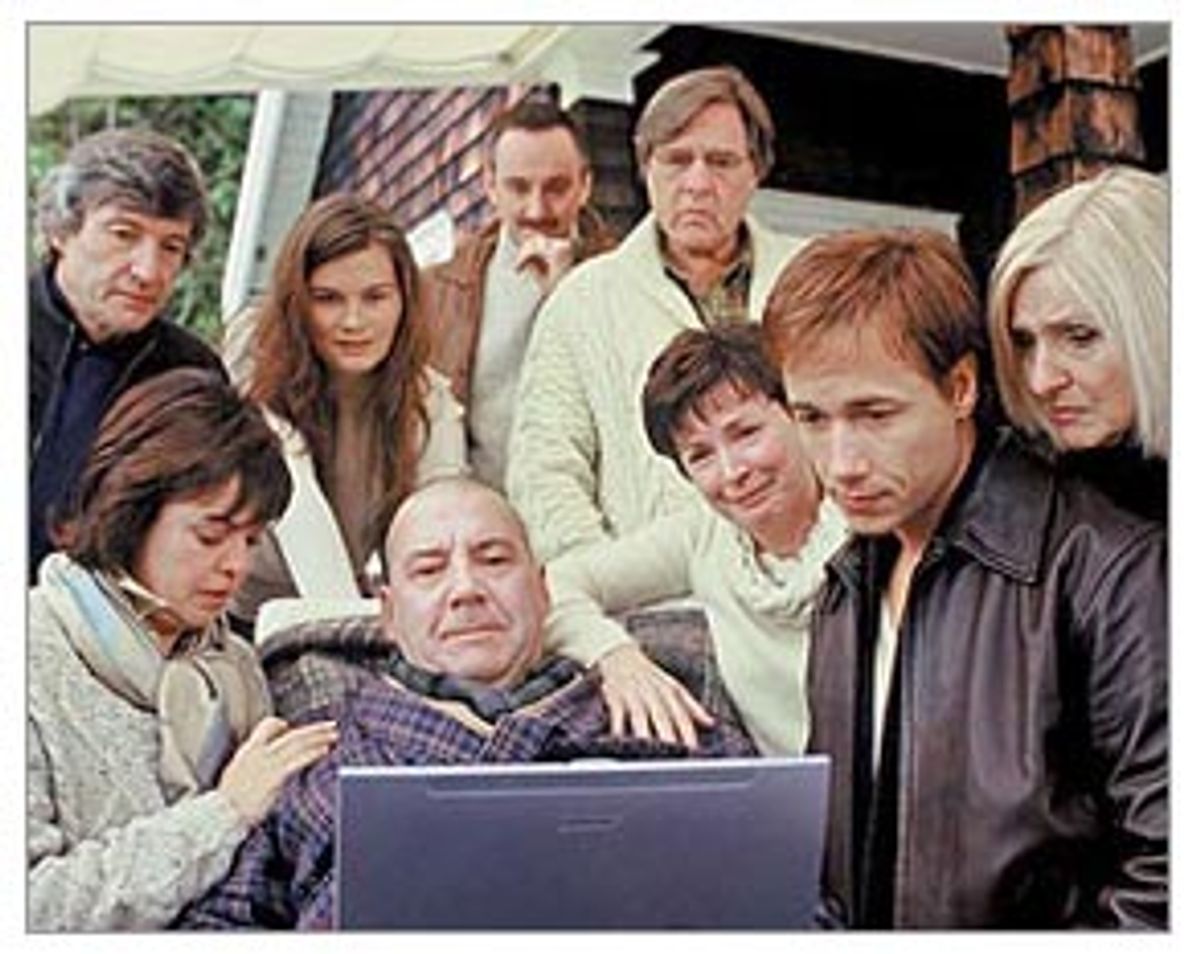

Rémy's old friends are the same ones we met in "Decline": Pierre Curzi as the perennial bachelor (he's now married to a much younger woman and has two small children); Yves Jacques as the outrageous gay aesthete, now living in Italy with his lover; and Dominique Michel and Louise Portal as two of Rémy's former mistresses, who sweep into town to remind everyone how hot they once were. The characters talk and laugh and reminisce, taking stock of the way their lives have diverged. And they lament how much the world has changed. The movie's title comes from the way a pointy-head on TV intones that Sept. 11, 2001, was the day "the barbarians" invaded North American soil, but it also refers to the way change invades all of us and the world we live in.

Which would all be well and good, if only Arcand's approach weren't so deliberate and stupefyingly superior. He's clearly going for real emotion here: One of the characters is, after all, dying, and he knows this is his last chance to connect with his children and his friends -- that's a subject that can't fail to be poignant.

But you have to be able to like Rémy and his friends at least a little bit to enjoy "The Barbarian Invasions." And the more they talked -- and they talk a lot -- the less I liked them. I wish there were more movies that dealt honestly and realistically with the sexuality of "older" characters (and remember that in Hollywood terms, anyone above the age of, say, 28 is considered "older"). But "The Barbarian Invasions" doesn't deal as realistically with sex as Arcand seems to think it does. The characters act as if their generation has cornered the market on sex -- as if no one before or since had ever been as cool or as free about it as they were. Their smugness seeps right through their randy jokes, and they don't seem to realize that smugness is never sexy.

They drive us to sympathize with the rather uptight Sébastien, who at least has a grasp of how the world works: Frustrated with the level of care his father is getting (the movie is perhaps most successful as a pointed comment on the state of the Canadian healthcare system), Sébastien throws money at the problem. While his actions are viewed as crass, they do get Rémy a much nicer room in the overcrowded hospital, among other benefits.

Spending money is how Sébastien shows love. That may be anathema to overeducated boomers like the ones in "The Barbarian Invasions," people who claim to value ideas over money. The problem is that even though he's emotionally remote, Sébastien seems more engaged with the world than they do. Even when Rémy and his friends are discussing important historical or social events, they seem much more interested in the sound of their own voices than in the universe around them. The noise of their faux-intellectual yakking is deafening. Money talks, and sometimes, unfortunately, so do people.

Shares