"Barbershop" is one funny movie. But even more laughable are the outrageous responses to the film by two prominent black leaders.

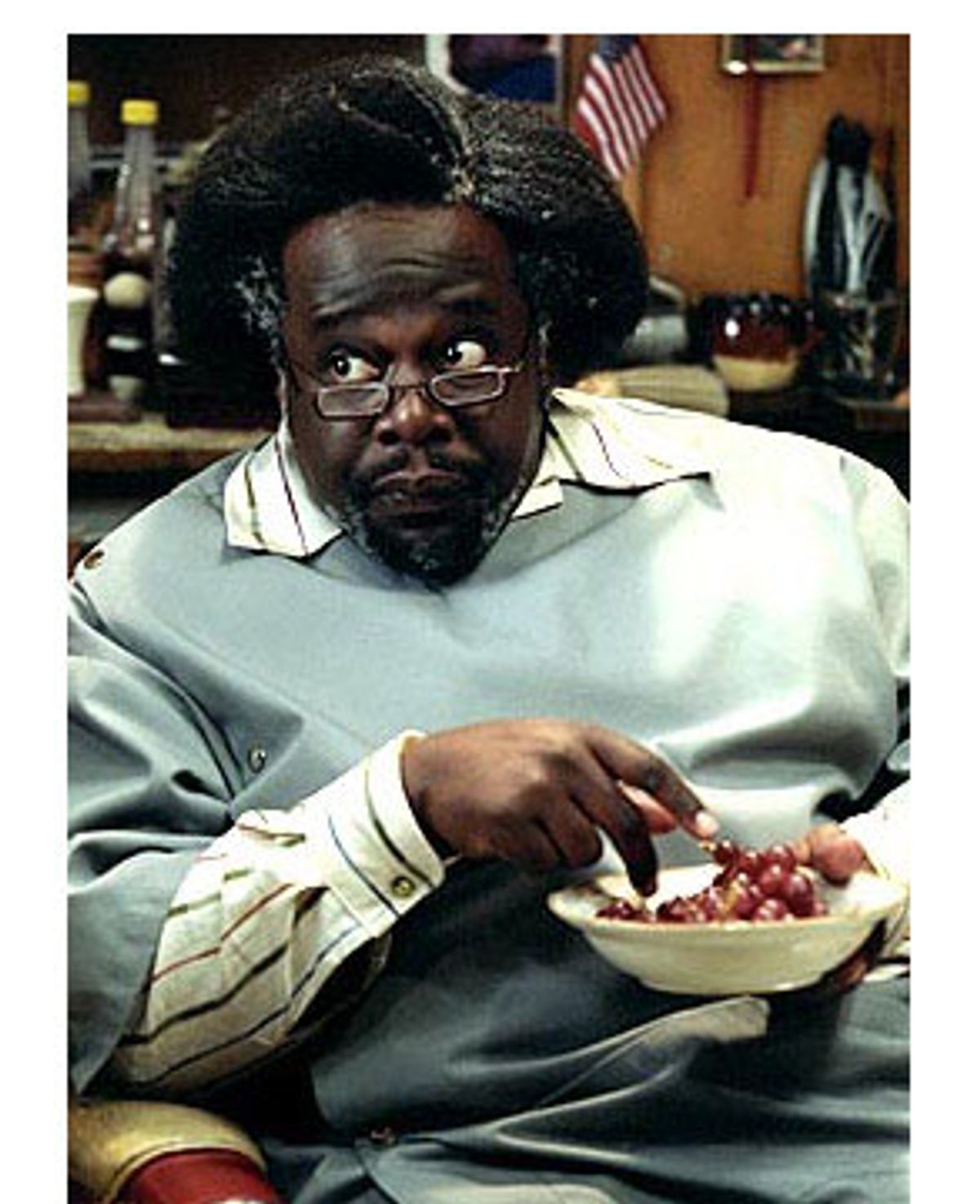

Talk about going over the top. The Rev. Al Sharpton demanded an apology for, and Jesse Jackson was piqued over, two minutes of irreverent humor in the film. They actually took seriously the deliberately silly and inane crack by Cedric the Entertainer that the towering contributions of Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. to the civil rights struggle had no value.

Certainly none of the characters in "Barbershop" believed it. They immediately jumped all over him.

In fact, it's due in large part to the magnificent contributions of Parks, King and other legendary civil rights heroes that entertainers such as Cedric the Entertainer and the writers, director and producers of "Barbershop" -- all of whom are black -- could even get a major Hollywood studio to bankroll their film. The civil rights struggle also opened doors to blacks in education, business and other professions. The crumbling of those barriers has given blacks the awesome economic muscle to help make "Barbershop" a smash box office success.

But Cedric's enormously off-base wisecrack about black leaders is nevertheless complex. Underneath it flows a current of disenchantment and resentment that many blacks feel toward those who designate themselves -- or more likely are designated by whites -- as "black leaders."

Many of these leaders are middle-class businesspeople and professionals. Their agendas and top-down style of leadership are remote, distant, and often wildly out of step with the needs of poor and working-class blacks. They often approach tough public policy issues -- such as the astronomical black imprisonment rates, the dreary plight of poor black women, black homelessness, black-on-black crime and violence, the drug crisis, gang warfare, and school vouchers -- with a strange blend of caution, uncertainty and wariness. They keep counsel only with those black ministers, politicians, professionals and business leaders whom they consider respectable and legitimate and who will blindly march in lockstep with their program.

Worst of all, they horribly disfigure black leadership by turning it into a corporate-style competitive business in which success is measured by piling up political favors and corporate dollars. The sad thing is that it wasn't always this way. For decades, mainstream black organizations such as the NAACP relied on the nickels and dimes of poor and working-class blacks for their support. This gave them complete independence and a solid constituency to mount powerful campaigns for jobs, better housing and higher-quality schools, and against police violence and lynching.

The profound shift in the method and style of black leadership began in the 1970s. After the murders of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, the collapse of the traditional civil rights organizations, and the destruction and co-optation of militant activist groups, mainstream black leaders, politicians and ministers did a sharp about-face. They quickly redefined the black agenda as gaining admission into more country clubs, buying bigger and more expensive homes, taking more luxury vacations, starting more and better businesses, electing more Democrats, and grabbing more spots in corporations, universities and the professions.

The biggest gripe many blacks have about some black leaders is that they give to themselves the sole right to speak exclusively on behalf of all blacks. That is much evident in Sharpton's demand that MGM excise Cedric's politically incorrect quip from a film that has already been seen by thousands -- as if the demand to slice is made on behalf of all blacks.

Black leaders get away with this arrogant presumption because many whites regard blacks as so far outside the political and social pale that they see them as monolithic. Whites are profoundly conditioned to believe that all blacks think, act and sway to the same racial beat. They freely use the words and deeds of the chosen black leader as the standard for African American behavior.

Then, when the beleaguered chosen one makes a real or contrived misstep, he or she becomes the whipping boy for many whites. Blacks are then blamed for being rash, foolhardy, irresponsible and prone to shuffle the race cards on every social ill that befalls them.

"Barbershop" is more than a comedic, slice-of-black-life film. It spotlights the historic role that barbershops in black and probably other ethnic neighborhoods have traditionally played in allowing working people to vent, swap gossip and information, keep abreast of social and political issues, and express their own special brand of ethnic in-group humor. There is no need to cut out or apologize for that.

Shares