Less violence, more poetry: For believers and nonbelievers alike, the big Catholic movie to see this season is not Mel Gibson's "The Passion of the Christ" but Guillermo del Toro's "Hellboy." "Hellboy" is based on a comic -- the Dark Horse series of the same name by Mike Mignola -- and not on the Gospels, and its hero is a butt-kicking, resolutely working-class red demon, as opposed to a peaceable prophet. But like most stories based on comic books, "Hellboy" has a deeply moral underpinning, and that's not lost on del Toro: The movie riffs on the idea that the seeds of both good and evil are within all of us, and we choose which ones to cultivate. In the picture's final scene, a character wonders aloud, What makes a man a man? The answer, he decides, is that "it's the choices he makes. Not how he starts things, but rather, how he decides to end them." "Hellboy" is like a catechism class run by the X-Men.

Which is to say that watching it is a pleasure rather than a chore: The religious undercurrents of "Hellboy" are metaphorical rather than tediously literal. Del Toro may be fully in touch with the pageantry of Catholicism; the movie's imagery includes a beautiful woman enrobed in blue flames and a rosary with supernatural powers. But "Hellboy" doesn't exist to instruct or to preach at us. If anything, del Toro ("Blade II," "The Devil's Backbone") proves that stylishness is its own kind of spirituality. "Hellboy" is one of the most poetic comic-book adaptations to come along in years, yet it never loses its sense of lightness and fun -- del Toro gives it just enough screwball nuttiness to keep it from bogging down. When good triumphs over evil in "Hellboy," as it inevitably does, we don't feel as if we've been run over by a steamroller; instead, we're buoyed up and held aloft. The gravity of this comic-book movie is virtually weightless.

In the prologue to "Hellboy," we learn that during World War II, the Nazis were holed up on a remote Scottish isle, busying themselves with a secret plan: Via a goose-step-voodoo commingling of science and black magic, they would rule the world by unleashing an unspeakable evil. The plan is foiled, for the time being at least, by the Allied forces and their guide, a brainy professor by the name of Trevor Broom. But the mastermind behind the plot, the evil Gregor Rasputin (yes, that Rasputin, who, it turns out, never really died at all but has unlocked the secret of everlasting life), manages to disappear through a supernatural portal just in the nick of time, which means he'll surely appear later -- sometime in the early 2000s, as it turns out -- to stir up more trouble.

As Broom and the Allied soldiers explore the island, they come upon a slimy red infant with a curvy, twitching tail, nascent, stumpy horns emerging from his forehead and a right forearm that looks like a small block of concrete. Broom lures the frightened creature into his arms with a Baby Ruth candy bar, and takes him home to raise him as if he were his son. Hellboy (Ron Perlman), as Broom and the soldiers come to call him, grows up to be a strapping, weight-lifting, cantankerous, scarlet-skinned, beer-guzzling hunk of a man who's not a man at all but a demon. As a baby, he was brought to earth by Rasputin as a harbinger of the Armageddon, but under Broom's care, he has instead turned into a champion and protector of all that is good, fending off every giant, hungry, moist, tentacled critter that threatens to destroy humanity.

And, as it turns out, there are a lot of them, thanks to the nefarious Rasputin (played with gleaming deviousness by Karel Roden), who reappears on earth hoping to get his previously scuttled plan back on track. Hellboy doesn't have to work alone: He's part of an extended family of misfits (not unlike those bigger comic-book legends, the X-Men) that includes his adoptive father, Broom (John Hurt, in a touching, finely calibrated performance); an elegant, telepathic fish-man named Abe Sapiens (he's played with boundless grace by Doug Jones; David Hyde-Pierce provides his voice) who can read four books at once, provided there's someone around to turn the pages for him; a forthright yet shy young woman, Liz Sherman (the demurely deadpan Selma Blair), who can start fires at will with her fingertips; and a young Secret Service type, John Myers (Rupert Evans), who has been assigned to look after Hellboy but who also finds himself attracted to Liz, oblivious of the fact that Hellboy himself is not so secretly in love with her.

There's also a svelte, sand-filled, metal-masked puppet-man who runs on windup clockworks, but let's not get ahead of ourselves: The plot of "Hellboy" (it was adapted by del Toro and Peter Briggs) may be convoluted, but it at least appears to make sense while you're watching it, which is more than you can say for most modern thrillers.

But the story line of "Hellboy" hardly matters at all. This is the kind of movie you watch for its aura, for its appealing characters, for its marvelously sustained seriocomic romantic mood. Particularly in its treatment of the relationship between Hellboy and Liz, there are times when "Hellboy" resembles Bryan Singer's "X-Men," one of the few other recent comic-book adaptations that understood that comics aren't just about action, but also about mood and language and lyricism. Even though cinematographer Guillermo Navarro makes "Hellboy" look rich and expensive -- its color palette is all smoky reds and muted, steely grays -- the movie doesn't have the extravagant, noisy flash of the X-Men pictures: It's more intimate and more organic than either "X-Men" or its clumsier sequel "X2." The production design, by Stephen Scott, is often reminiscent of that of Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet's "City of Lost Children" (in which Perlman also appeared). The movie's imagery is drawn from dreams that teeter on the edge of nightmares: There are giant silvery clock gears, a Russian cemetery draped in snow like crocheted lace, and a huge, shining moon that's both benevolent and threatening. In one of the movie's loveliest scenes, Hellboy and Liz sit in the quiet nighttime garden of a mental hospital, surrounded by small trees that have been wrapped in plastic and lit from within like translucent Chinese lanterns.

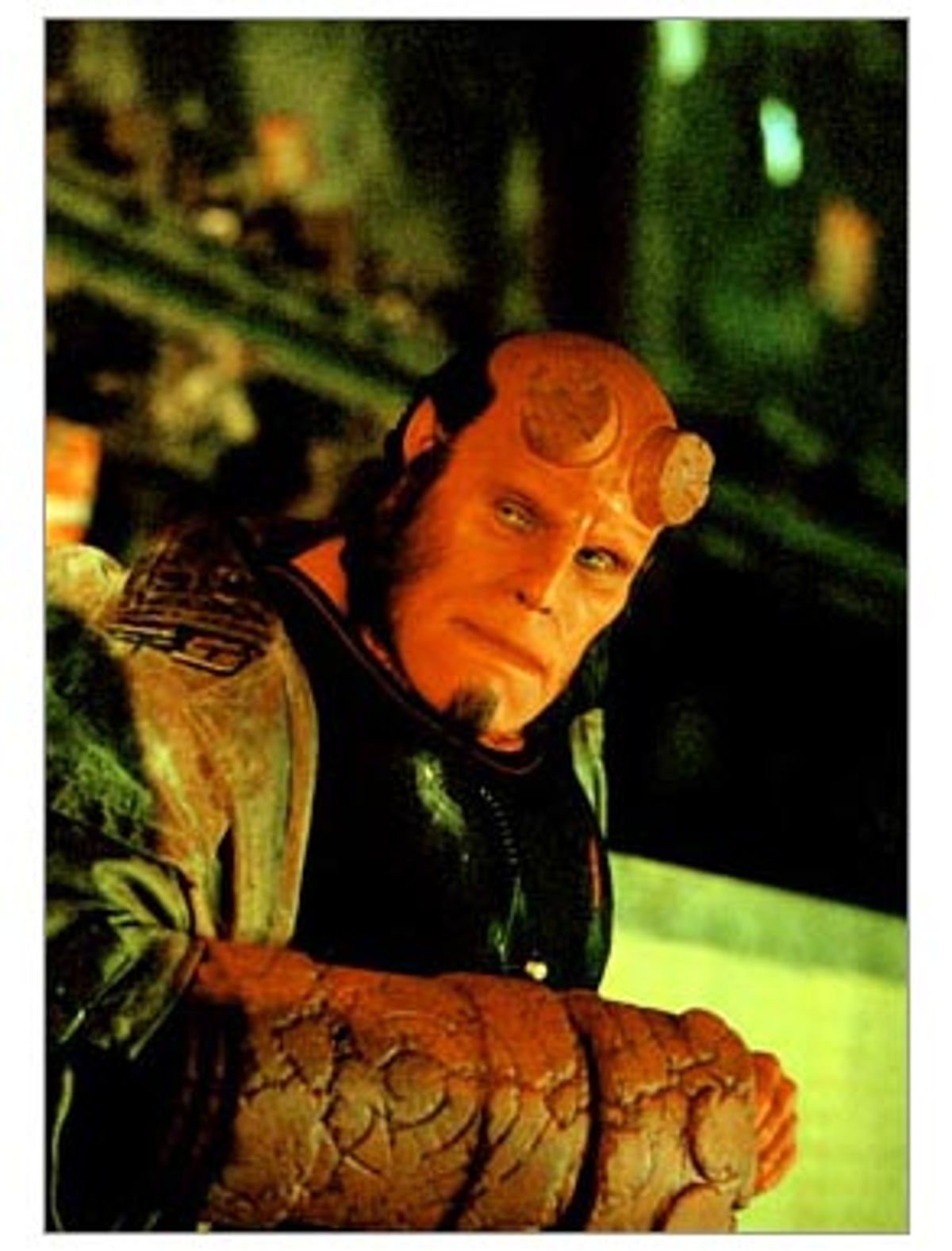

Like Tim Burton (whose "Batman" remains one of the finest comic-book adaptations of all time) before him, del Toro understands that the look of a comic-book movie can go a long way in setting its tone. But he isn't so obsessed with surfaces that he loses sight of his characters, and that's particularly important when it comes to orchestrating a movie around a lead actor who's hidden beneath pounds of makeup and prosthetics, as Perlman is here. His performance is brazenly delicate: On the surface, Hellboy is something of a hellraiser, but Perlman lets us see straight into his smoldering soul. In his downtime Hellboy lifts weights and puffs on stubby stogies (simultaneously, no less). He has no patience for foolish people and stupid questions: When poor Agent Myers notices that a sticky, gooey, bloodthirsty critter has affixed itself to Hellboy's arm, he blurts out, "What's that?" to which Hellboy replies crustily, "Lemme go ask."

But Hellboy also has a great fondness for cats (as pets and not, thank goodness, as snacks) and his living quarters are crawling with them -- they mew and clamber and twitch their tails just as restlessly as Hellboy twitches his. Del Toro treats Hellboy's tenderness as a delectable joke (at one point he rescues a crate full of kittens from a subway platform that's about to be demolished by a massive creepy-crawly), but he also knows it's the linchpin of the movie, the immovable center around which it rotates. When Hellboy attempts to confess his love to Liz, he mutters an apology about the way his face looks, passing his giant, clumsy hand dismissively across his perilous-rock-ledge brow and his barely present nose, which manages to be both hooked and flattened at the same time (although it is also mysteriously fine and noble). Left to their own devices, his horns would be giant, water-buffalo-style affairs, but he files them down to nubs that look like big slices of pepperoni -- "to fit in," as one character wryly puts it.

Next to Blair, who is fine-boned and tiny, Perlman's Hellboy is a rough, hulking thing; you can understand why he wouldn't even feel entitled to touch her. But even from beneath those layers of makeup and costuming, Perlman radiates gentleness and warmth. It's no surprise that these two misfits -- one of whom looks completely normal but who also, unfortunately, has the power to inadvertently fry entire villages with her mere touch -- find comfort in each other. Hellboy, like many (if not most) comic-book heroes, is an outcast who has turned his oddities and flaws into a brilliant advantage. But having superpowers doesn't mean you can escape pain; it may, in fact, mean that you're destined to suffer more of it. That's a Catholic idea if ever there was one, but instead of focusing on the brutality of it, del Toro helps us see its beauty. It's the kind of X-ray vision more filmmakers could use.

Shares