Toward the end of "Kill Bill, Vol. 2" David Carradine delivers a speech that, like most seemingly aimless Quentin Tarantino monologues, meanders its way to its absurdist point. The subject is superheroes. Carradine's Bill is the mack daddy of a squad of (now-decimated) female assassins; the Bride (Uma Thurman) is hot on his trail -- he's the ultimate object of her quest for vengeance. In his speech, the coiled-snake son of a bitch says that his fave-rave superhero is Superman. Why? Because unlike Batman or Spider-Man, Superman's true identity is Superman -- it's nerdy Clark Kent that's the alter ego.

It's not hard to hear that speech as the closest we'll ever get to naked confession from Quentin Tarantino. When Tarantino goes into his hyperactive routine on late-night TV or on DVD extras -- playing the fanboy who revels in sleaze and who can pull more forgotten references out of the air than every issue of Cashbox and Psychotronic combined, the director who combs the streets of L.A. like a bloodhound to track down that character actor he loved in that forgotten TV show or grindhouse movie years back -- we're seeing a carefully constructed persona, the creation on which Tarantino has expended the most energy and time.

It's not that his enthusiasms aren't genuine. But there are two problems: Even at Tarantino's most entertaining, you're always aware of how much work has gone into putting together the genres and pop-culture references that dot his movies. They never have the feeling of something that just popped out of his brain; it's as if they've been planted with the sort of deliberateness that kills spontaneity. (At times, Tarantino seems as deliberate a filmmaker as Clint Eastwood, if nowhere near as plodding.)

But the bigger problem in sustaining our belief in the Tarantino persona is that -- once -- he let us see what was beneath the alter ego. In "Jackie Brown," to which I stupidly gave a middling review when I wrote about it for Salon in 1997, Tarantino winnowed his omnivorous pop-culture obsessions down to a manageable quartet -- Pam Grier, '70s soul, Robert Forster and Elmore Leonard novels. I should have realized that what he came up with was not only one of the great popular entertainments but also one of the most moving American pictures about the compromises of middle age.

On the "Jackie Brown" DVD, Tarantino calls it his Howard Hawks movie, and he's right. The film operates in the same spirit as Hawks' late masterpieces "Rio Bravo" and "Hatari!" Like those movies, "Jackie Brown" is nearly all talk, a series of beautifully written and played dialogue scenes that serve as subtle revelations of character. And the exquisite performances of Pam Grier and Robert Forster achieve the ease and conviction that, to borrow a phrase from the critic James Harvey about "Rio Bravo," seems less acting than pure behaving.

Perhaps because "Jackie Brown" was a critical and commercial disappointment, Tarantino chose to return to the role of trash connoisseur with a vengeance. It was obvious from just the first part of "Kill Bill" that Tarantino was cramming in as many genres and pop-culture references as he could. This was less a movie than a convention, a place to stroll down aisles and be reminded of junk artifacts you didn't know you knew.

Martial-arts movies and Hong Kong action movies were the hallmarks of "Vol. 1." In "Vol. 2" westerns have taken over, particularly the work of Sergio Leone. Selections by Leone's composer Ennio Morricone are all over the soundtrack. And "Vol. 2," set largely in Texas, California and Mexico, basks in wide landscapes and spare exchanges. Robert Richardson's cinematography mimics Leone's use of enormous close-ups, where the iconography of a face overpowers the iconography of the landscape.

The film is paced like a western, slow and deliberate. Maybe because it's not one action scene after another, it doesn't fall into the tedium that "Vol. 1" did (even though it's a half-hour longer). Some of the studied laconicism works, particularly in the two encounters between Bill and the Bride that bookend the movie. The first is a flashback to the wedding-chapel massacre where Bill and his hit squad left the pregnant Bride for dead and murdered her groom and wedding party. The second is their final encounter when the Bride has finally tracked Bill down.

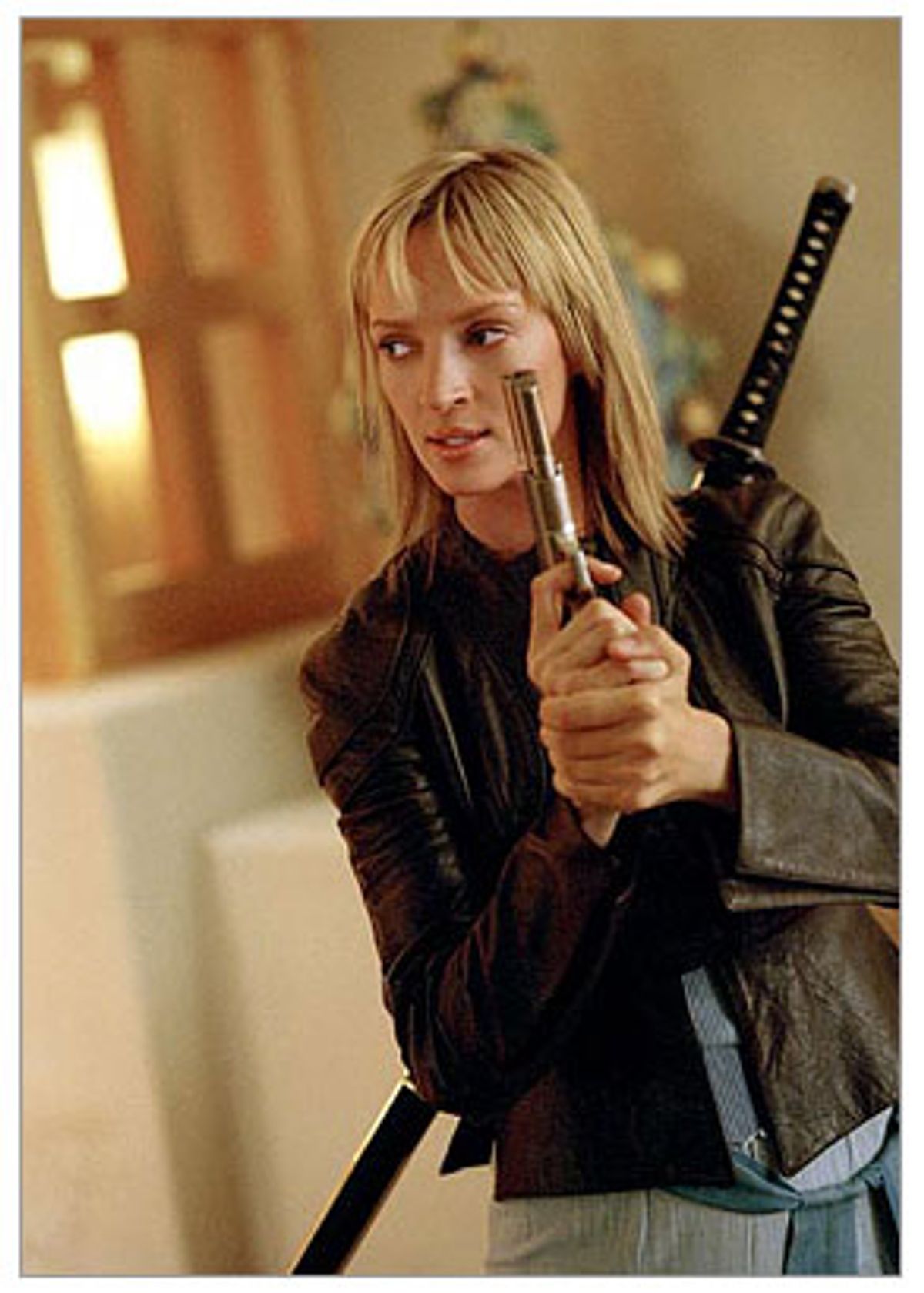

Thurman and Carradine are awfully good together. They capture the connection that exists between deadly foes, the knowledge that neither can hide from the other. There's wit and a spacy yet exact sense of timing in Carradine's aging stoner delivery, and he's one of those performers who looks better with the lines of age on his face. Uma Thurman is used more as Tarantino's muse and as a (terrific) camera object. But she knows the expression a performer can bring to a modeling job. She has a leonine quality here, and there's a febrile sense of controlled rage in the slowness of her limbs before she executes some martial-arts move. And when you see Carradine and Thurman facing each other in profile, you know exactly why Tarantino wanted to put them together. They both have the same lanky, American frame, the same sense of sly underplaying.

How well these two match up is at the heart of what I think is the one genuinely subversive twist in the movie. Tarantino knows that we're expecting a huge confrontation when Bill and the Bride finally meet again (the picture is called "Kill Bill," after all). And he gives it to us -- but in words rather than in physical action. We recognize the climax on the rebound; it happened while we were waiting for the ultimate fight sequence. The way Tarantino throws away what could have been a predictable finish by choosing to emphasize character and performance over spectacle is a sly rebuke to what passes for craftsmanship in mainstream movies where final confrontations are simply excuses for elaborate special effects and multiple endings.

It might surprise some people that the violence in "Vol. 2" is relatively discreet. When assassins charge into the church to kill the Bride and her wedding party, the camera stays outside. But there are scenes with Tarantino's unfortunate taste for sadism, particularly the confrontation between the Bride and Daryl Hannah's one-eyed Elle Driver. (It's hard to get people who don't like action movies to understand that what audiences are responding to in most of them is not physical violence but the kinetic thrill of speed and movement. In Tarantino, though, the emphasis has always been on physical pain.)

Still, for all the craft that's gone into "Kill Bill, Vol. 2," despite the chance Tarantino has taken in departing from the wham-bam movement of the first half, my final reaction to the movie is, so what?

There's no shame in having a taste for trash, particularly if you're an American director. Our national film heritage is largely based on genre films -- screwball comedies, film noir, westerns, melodrama, gangster movies, musicals. And you don't even have to aim as high as the best of any of those genres to see the attraction of the trashy exploitation and martial-arts movies Tarantino is drawn to.

But Tarantino doesn't poeticize his fixation on American pulp (as the French nouvelle vague directors did). He doesn't use the hokiest conventions and make them seem free of calculation, imbued only with the desire to please an audience, as the best Hong Kong filmmakers have done. He doesn't give the emotional or mythic weight to the faces that appear before his camera in the way that Sergio Leone did. The faces in Leone's "Once Upon a Time in the West" are familiar to any moviegoer -- Henry Fonda, Charles Bronson, Claudia Cardinale, Jason Robards, Woody Strode, Jack Elam. And yet Leone makes you feel as if they have welled up out of the collective unconsciousness of our (real and imagined) past -- or at least as if they'd just descended from Mt. Rushmore.

Tarantino is very good at replicating the surface of the movies he loves. The opening black-and-white shots of Uma Thurman driving and addressing the camera have the phony rear projection and silvery luster of '40s noir. The outdoor shots in the scenes set in America have the crystal-clear views of vast vistas familiar from Leone and John Ford. The flashback where the Bride trains with a Chinese kung fu master (Gordon Liu) have the abrupt camera movements of Chinese martial-arts films and the graininess of prints that have been playing endlessly in dubbed versions on UHF TV stations for years.

It was during this section that the gap between what Tarantino intends and how his audience takes him became apparent. Clearly, for Tarantino, the movies he is aping here are objects of reverence (that he seems to revere nearly everything he's ever seen is another problem). But because he imitates his influences more than transforms them, they look, to his largely young audience, like some sort of knowing parody. The audience I saw "Kill Bill, Vol. 2" with laughed during the martial-arts training sequence because what they were looking at seemed indistinguishable to them from the junky movies they saw on Saturday-afternoon TV as kids.

Tarantino's movies don't raise any questions about our relation to our movie past. You can't imagine him asking himself, as directors like Coppola and Altman did in "The Godfather" films or "McCabe and Mrs. Miller," how we preserve what we love from our movie past while making them seem an expression of our own time. The message of Tarantino's movie is indiscriminate enthusiasm, where the junkiest B-movie exists on a par with a John Ford or a Leone western, where some slapped-together kung fu outing is the same as the best of King Hu or Tsui Hark.

When "Reservoir Dogs" and "Pulp Fiction" came out, I was struck by the number of people who told me that they couldn't usually sit through violent movies but that they liked Tarantino. And of course it makes sense because, unlike Arthur Penn in "Bonnie and Clyde," unlike De Palma or Peckinpah, Scorsese in "Mean Streets" and "Taxi Driver," Coppola with "The Godfather" films, there are no moral ambiguities, no simultaneous sense of repulsion and rapture in Tarantino's violence. (I'd argue there isn't even the presence of movie-simplified notions of honor and duty that you find in John Woo's Hong Kong movies.) It's just a kick -- and if Tarantino has become a director of our time, part of it is because (with the exception of "Jackie Brown") he makes movies that are easy to slough off, in which all culture is ultimately disposable.

We know what it means, in "Breathless," when Belmondo pauses in front of a movie-lobby glossy of Humphrey Bogart. What does it mean in "Kill Bill, Vol. 2" that part of the story figures around the grave of a woman called Paula Schultz? Nothing, except that it's a reference to "The Wicked Dreams of Paula Schultz," a 1968 Cold War comedy starring the cast of "Hogan's Heroes." What does it mean that Bill names the truth serum he has devised the Undisputed Truth? Noting, except that it's a reference to the '70s soul band who had a hit with "Smiling Faces Sometimes." What does it mean that, as in "Vol. 1," the Bride's name is bleeped out on the soundtrack whenever anyone speaks it? Less than nothing, since the revelation of her real name doesn't spring some plot twist that had been kept hidden from us. It appears to be in there solely so that Tarantino can make a nod to the same device in Godard's "Made in USA."

After a while, "Kill Bill, Vol. 2" is like being on a tour bus. There's blaxploitation mainstay Sid Haig as a bartender. And there's Bo Svenson, whom Tarantino no doubt loved in "Part 2 Walking Tall," as a Texas preacher. Oh, and there's a poster for the Charles Bronson movie "Mr. Majestyk," which was based on an Elmore Leonard novel. The split screen is an homage to Brian De Palma. And the bit where Uma Thurman walks into the diner covered in dirt and blood? Yeah, that's a nod to "Freeway."

What does any of this finally add up to except that Quentin Tarantino has seen a lot of movies? And what does "Kill Bill" finally add up to? The final plot twist suggests that "Kill Bill" has enough of a premise for a 90-minute revenge movie. As the denouement of a nearly four-hour movie, it's not nearly enough. Perhaps it could have been if Tarantino had found some way to unify it all into a sweeping celebration (elegy?) for action cinema, the way, in "Once Upon a Time in the West," Leone makes you feel you're seeing the passing of a historical epoch and an entire movie genre. There's no doubt that "Kill Bill" is an epic, and no doubt of the skill that's often apparent. But what it leaves us with is awesomely trivial.

Shares