“Super Size Me” is the latest example of a specific type of instructional nonfiction filmmaking in which the director also appears as the lead character — the approach taken by Michael Moore in pictures like “Roger & Me.” In this case, director Morgan Spurlock, dismayed by American obesity statistics (particularly among children), decided to eat nothing but McDonald’s fast food for a month and film the experience.

You have to be at least marginally self-centered to put yourself at the core of your own movie. And even if your aim is to reveal the sleazy irresponsibility of corporate America, the risk you run — one that Moore seems completely clueless about — is that you might come off as nothing more than the spoiled, foot-stomping superstar of your own cause. That is to say, in championing the cause of the “little” people, it’s easy to fall in love with how smart you think you are.

Who knows how he pulls it off, but Spurlock generally avoids those traps in “Super Size Me.” Spurlock is certainly a presence in the movie: We follow him as he treks to McDonald’s restaurants across the country, from New York to Los Angeles to points in between, including Houston (which, at the time he made the film, was statistically the “fattest” city in the nation) and Detroit (which had stolen that dubiously honorable No. 1 slot by the time the film was completed). And the whole enterprise obviously stems from his questioning vision: It’s a good example of an individual’s recognizing that the political is also personal, particularly when it comes to the food we eat.

But “Super Size Me” is exploratory, as opposed to being just numbingly didactic, and that’s what makes it so engaging. Spurlock was inspired to examine the possibility that Americans are “eating ourselves to death” when he read about the two teenagers who sued McDonald’s last year, claiming the company had caused their obesity. But Spurlock doesn’t automatically assume the “big corporation bad, little guy good” stance — in other words, he doesn’t seem to have a lot of patience for lazy righteousness. (It’s worth noting that Spurlock’s career as a filmmaker has included music videos and corporate work. His bio notes that he won an award for a corporate image piece he did for the Sony Corp. — which suggests not that Spurlock is necessarily sympathetic to big business, but that he has some sense of how it works, and of how it wants the public to perceive it.) At one point Spurlock just comes out and asks the question, “Where does personal responsibility stop and corporate responsibility begin?” The key is that he asks it without smugness — in other words, it’s a question to which he doesn’t already know the answer.

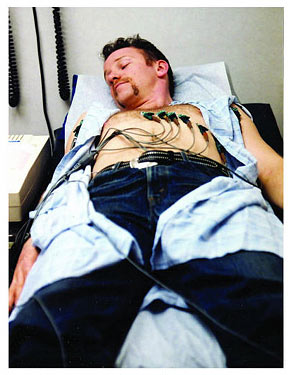

“Super Size Me” shows Spurlock eating (and, in one scene, regurgitating) masses of fast food, day after day. His plan requires that he eat only from the McDonald’s menu (water is included), he has to eat everything on the menu at least once, and he can’t exercise. (A New Yorker, he doesn’t even do the normal day’s worth of walking most Manhattanites do, opting to take cabs everywhere.) Along the way, Spurlock is supervised by various doctors and health professionals, one of whom warns him that he may be pickling his liver with this diet high in fat, sodium, refined sugars and Lord knows what else.

Spurlock is a likable presence, thank goodness. He doesn’t come off as whiny or self-serving or even particularly damning of the concept of fast food in the first place. In fact, he admits to liking it. At the beginning of his 30-day ordeal, he holds up a Big Mac he bought in New York’s Chinatown and marvels at how beautiful it is, noting that it’s the first one he’s seen in real life that looks “just like the picture.”

But by the end of his stint, Spurlock isn’t quite the same man: Filmmaking is both an art and a craft, and grimy lighting and woozy camera angles can be used to make anyone look bad. But toward the end of his enforced march, Spurlock complains of chest tightness and fatigue. He gets winded climbing just one flight of stairs. And he looks, to say the least, lousy: Puffy, pale and depleted, he’s hardly the vigorous, cheerful guy we met at the beginning. By the end of his ordeal, this fit, healthy fellow had gained some 25 pounds (we’re told it took him more than a year to lose all of it) and had subjected his vital organs to high levels of stress.

Spurlock’s personal trial may be the main gimmick of the movie. But ultimately, as interesting (and often amusing) as it is, it feels almost interstitial. Spurlock really does want to know exactly how damaging fast food is to the nation (and to the world), and to that end, he interviews a host of experts, from nutritionists, to school phys-ed instructors and lunchroom workers, to David Satcher, the former U.S. surgeon general, who rang the fast-food warning bells early. He interviews a surprisingly trim-looking Big Mac enthusiast (he eats at least one of the things every day), and talks to a smooth-talking rep from one of the big food-industry lobbies, who starts out blathering about how consumers need to be “educated” about nutrition and eventually gets tangled in his own doublespeak, blurting out, bizarrely, “We’re part of the problem, and part of the solution.” (At the end of the movie, we learn that the man is no longer in the lobby’s employ.)

We also see Spurlock placing phone call after phone call (at least 15 of them) to the McDonald’s corporate offices in an effort to reach its director of corporate communications for comment. Spurlock is persistent but polite, and still he gets nowhere. (Contrast this with Moore’s shambling into the lobby of GM’s corporate headquarters, cameraman in tow, and then professing shock and dismay that he isn’t graciously ushered straight into the bigwig’s office.)

Spurlock knows how big companies work, but his patience with them has its limits. “Super Size Me” comes across, for the most part, as well reasoned. Still, there’s plenty in “Super Size Me” that’s more heavy-handed than it needs to be: When Spurlock loses his Super Size-lunch, the camera shows us the chunky mess on the ground outside his car window. (It’s the kind of cheesy art-house exploitation tactic that deserves a William Castle-style disclaimer: “No one will be admitted during the terrifying cookie-tossing scene!”) Spurlock films a team of doctors performing gastric-bypass surgery on an obese patient, showing a tangle of glossy flip-floppity organs and slimy interior whatchamacallits, all set to the “Blue Danube” waltz. It’s a whimsical and flimsy approach — Spurlock doesn’t need to be this cute to get his point across.

Then again, I did laugh when, after having explored the addictive qualities of fast food, Spurlock flashed multiple-screen images of Ronald McDonald with Curtis Mayfield’s “Pusher Man” playing in the background. (Incidentally, as Spurlock notes, in its corporate literature, McDonald’s does refer to its most loyal customers as “Heavy Users” and “Super Heavy Users.”) And Spurlock isn’t at all amused by the way McDonald’s markets to children, effectively brainwashing them into brand loyalty from a very young age — even though he understands, and doesn’t preach against, the fact that kids do enjoy going to McDonald’s. It’s part of American life.

Going to McDonald’s is — or perhaps that should be “was” — part of Spurlock’s life, too. His examination of our fascination with, and the dangers of, fast food is all the more believable precisely because, before he OD’d on the stuff, he enjoyed the occasional Big Mac as much as anyone else. Spurlock’s girlfriend, a vegan chef, also appears in the movie. We see her urging him, with zero success, to consider giving up meat altogether after his experiment is over. He lets her cajole him, but in the end, he just laughs at her. The point, it seems, is that life is too short to give up “bad” food forever. It’s also too short to eat it all the time.