The characters in the Argentinean heart-warmer "Valentín" spend so much time squabbling and yelling that after a while I began to long for a nice movie about a family of mutes.

Eight-year-old Valentín (Rodrigo Noya) lives in Buenos Aires with his grandmother (Carmen Maura). His father (played by the film's writer-director Alejandro Agresti) drops in occasionally between new girlfriends. The absence of Valentin's mother is, for most of the movie, unexplained.

For just two people in a rambling apartment, Valentín and his grandmother kick up quite a ruckus. She is always carrying on a private conversation with her husband, who died just a year before. When Valentin is present, she pesters him.

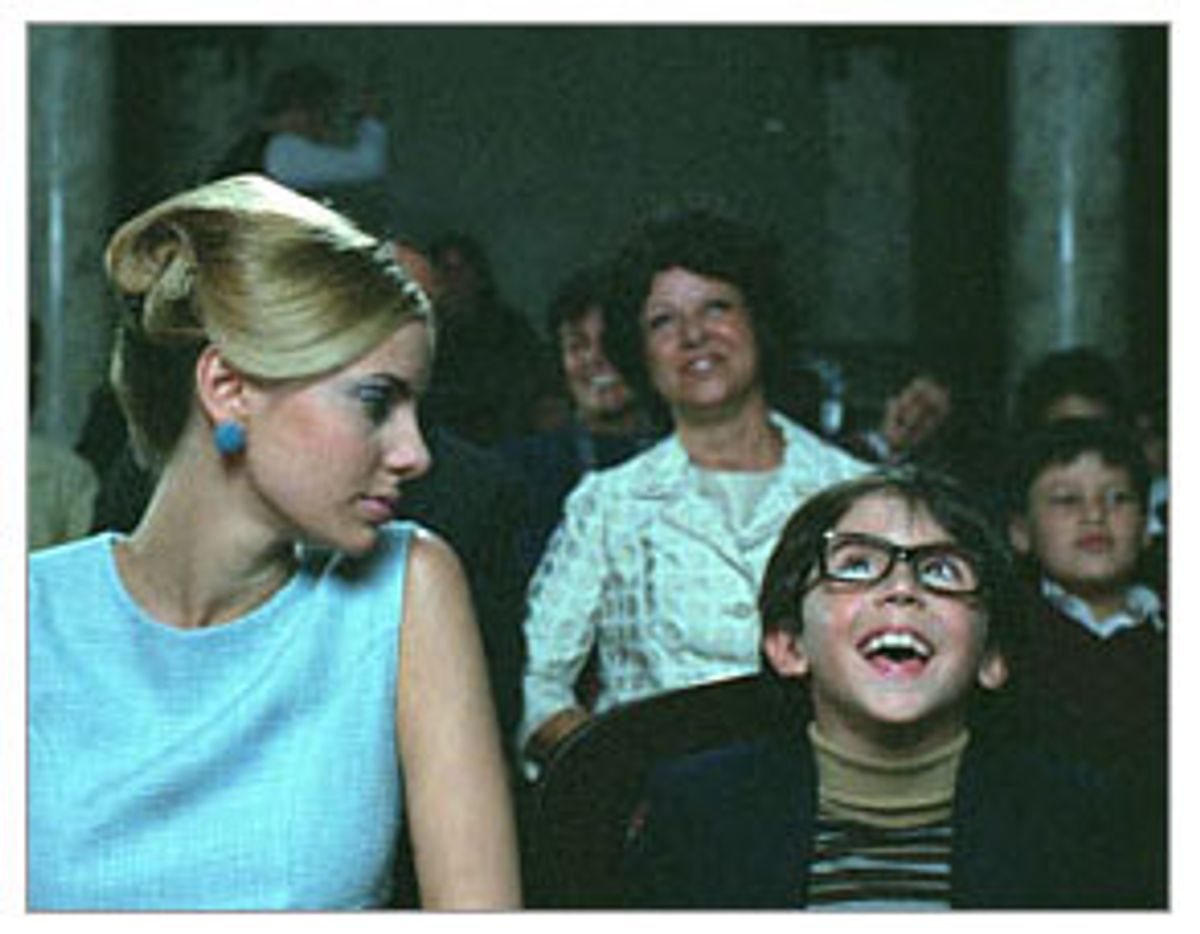

The movie is set in 1968, and except for one scene where a priest eulogizes Che Guevara as disgusted conservative parishioners walk out on him, you'd never know anything about the turmoil of the time, or that, for instance, Argentina was then a dictatorship. The thing that links the film most closely to the '60s is that, with his shag haircut and oversize black-framed glasses, Valentín looks like Mini-Me dressed up as Austin Powers.

Rodrigo Noya's performance isn't bad -- he doesn't resort to any of the typical heart-grabbing tricks that child actors sometimes do to make themselves adorable. But he doesn't have to when Agresti is so intent on making him adorable, framing him in huge close-ups looking dreamy and wide-eyed or melancholy and pensive. There's really nothing even an older, more experienced actor can do to give a performance some backbone and grit when he's working with a director who wants to make the audience melt at the sight of him.

Valentín dreams of being an astronaut, and there are some amusing moments of him clumping around in his homemade spacesuit. But his fascination with rockets and space seems a much-too obvious metaphor for the boy's wish to be free of the disappointments of his life.

And Agresti directs the scenes between Noya and Julieta Cardinali, as Valentín's dad's latest girlfriend, for icky poignance. We're never just free to watch the way Valentín charms this woman (who has been lovingly costumed by Marisa Urruti in subtly patterned shell dresses and knee-high boots that recall the glories of '60s popular fashion) because their scenes are directed so that we never forget Valentín's longing for a mother. (The revelation of the predicament of Valentín's real mother, which comes late in the movie, is subtly handled and yet its gruesomeness jars you; you can't help feeling Agresti hasn't thought through the grim repercussions of this revelation for Valentín.) The poignance keeps jabbing at us throughout the movie with Paul M. van Brugge's score swelling like a head cold in nearly every scene.

"Valentín" belongs to that class of art-house releases that are just as formulaic and manipulative as mainstream releases but that try to pass off faux sensitivity as artistry. The movie is soggy at the core, and it's no wonder Miramax is distributing it here. It perfectly fits the company's m.o. of playing to both "specialty" and mass audiences.

The one truly disgraceful thing in "Valentín" is the casting of Carmen Maura as the grandmother. In the Pedro Almodóvar films in which she made her international reputation -- pictures like "Law of Desire," "Matador" and "Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown" -- Maura was like a comic version of Anna Magnani, or a Simone Signoret who didn't play up the tawny heartache. To see this earthy, sexy actress who can't be beyond her 50s in the role of crotchety grandmother is dumbfounding. We're used to seeing it in Hollywood, but Europe has tended to allow its stars to age in the public eye without limiting them in this way (look at Catherine Deneuve or Claudia Cardinale). The treatment of Maura here is just one more example of how much "Valentín" shares with the mainstream dross it pretends to be better than.

Shares