There are no gods in Wolfgang Petersen’s “Troy,” only generals, and lots of them. The gods of Greek mythology are, after all, so 3,000 years ago. What modern audience would buy the notion of Zeus meddling, U.N.-style, in warfare between humans? “Troy” is a serious picture, “inspired,” as we’re told when the end credits start rolling, by Homer’s epic poem “The Iliad.”

Being “inspired by” one of the great works of literature can mean many things, up to and including outfitting Brad Pitt in a pleated leather miniskirt. But where does inspiration end and buffoonery begin? No one expects “Troy” to be a faithful adaptation of Homer’s magnificent whopper. But a deadweight epic like this one raises more questions than it answers, most notably, how do movies like these get made in the first place? It’s all well and good if the idea is to liven up the classics for a modern audience. But what’s the point of taking great material and making a desiccated, lumbering picture out of it? If the movie gods were paying attention instead of just counting their residuals, they’d be shooting thunderbolts from the tips of their fingers right now.

“Troy” isn’t so much a simplified retelling of “The Iliad” as a re-imagined version of it, told wholly without imagination. (Its screenwriter is David Benioff, who wrote the script for “25th Hour,” which he adapted from his own novel.) The handsome, featherheaded Paris (Orlando Bloom), Prince of Troy, makes moo-moo eyes at the looker Helen (Diane Kruger) across a crowded room, which happens to be filled with revelers celebrating the recently brokered peace between Troy and Sparta. But Helen is the wife of Menelaus (Brendan Gleeson), the king of Sparta. So when Paris makes off with her in a boat — he sheepishly reveals her presence to his older and much wiser brother, Prince Hector (Eric Bana), as if she were a kitten he’d smuggled aboard — Menelaus figures it’s as good a time as any to declare war. He enlists the aid of his greedy pig of a brother Agamemnon (Brian Cox), the king of the Mycenaeans, who’s eager to go to war not over any particular dame but simply so he can seize control of the Aegean.

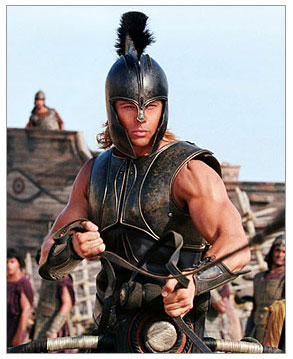

The tribes of Greece unite against Troy in one massive army; their greatest warrior is the sullen, brave Achilles (Brad Pitt), who seemingly can’t wait to die just so he’ll be written down in the history books that haven’t yet even been invented. “In 100 years, the dust from our bones will be gone,” his archenemy, the brave but sensible Hector, tells him. “Yes, Prince. But our names will remain,” Achilles recites back numbly, a theme he will repeat again and again during the course of the movie, using slight variations in language and tone, and once or twice, with a great deal of effort, talking and blinking at the same time, just to show he can do it.

“Troy”‘s theme, struck repeatedly like an out-of-tune gong, is that men must do great deeds so their names will be remembered. The complexities of honor, and even the horrors of war, are just little squiggles in the margins. Petersen has set up this “Troy” as a showcase for fabulous-looking people and for supposedly rousing battle and combat sequences. Yet almost every note “Troy” hits is wrong, from the casting to the shaping of the material to the picture’s flat, grubby-metallic look (its cinematographer is Roger Pratt, who shot Neil Jordan’s “End of the Affair,” as well as “Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets”).

Petersen wants to make sure we’re entertained every minute, and so “Troy” is packed with battle scenes, to the point where one is barely distinguishable from another. Zillions of extras march around purposefully, streaming off ships, out of wooden horses and over city walls. Arrows pling, swoosh and clank against armor, piercing a meaty thigh here, a sinewy shoulder there: One of the benefits of telling a story set in ancient Greece is the preponderance of scantily clad, musclebound warriors, but “Troy” doesn’t even work as erotic kitsch — despite all that tastily exposed flesh, the movie is too hamstrung by its own conventional notions of masculinity to have anything beyond a meathead’s understanding of sensuality.

I hear a chorus, and not just a Greek one, of voices out there saying, “Who cares? Brad Pitt is hunky!” That depends, I think, on how one defines “hunky.” Pitt isn’t much of an actor, but he’s sometimes serviceable as a swinging presence in pictures like Steven Soderbergh’s “Ocean’s 11.” In “Troy,” with his Coppertoned haunches, his sandy blond tresses and his leonine pout, he’s like a beach bum who’s been ordered by his parents to get a job — Jan-Michael Vincent with a bad attitude.

When we first meet Achilles, he’s sound asleep on a furry animal skin, his limbs entwined with those of not one but two sleeping beauties: This here red-blooded male isn’t to be mistaken for one of those “funny” Greeks, leather miniskirt or no. Later, we see him happily crossing swords with his cousin and bosom buddy Patroclus (who, despite his resemblance to one of the now-grown-up kids from Hanson, is really Garrett Hedlund). Later still, Achilles lounges on yet another animal skin, slugging wine from a cup, a disgruntled homo-neurotic advising Patroclus, who is dreamily devoted to him, to follow orders from no man. And even later, we see him rolling in bed with the sassy Apollonian priestess Briseus (Rose Byrne): After a bit of careful tussling in a brief competition to see who has the prettier hair, Achilles asserts his masculinity in the usual manner. We’re given to understand that he rams it in, but tenderly — Ancient Greece was a civilization, remember.

The battle scenes stink, the sex is bad, the beefcake is boring: At this point you may be wondering, does “Troy” at least give us a believable Helen — a woman whose face might, conceivably, have launched 1,000 ships? The answer is, unfortunately, no. With her sun-kissed, bland sweetness, Kruger is pretty enough in a Darien, Connecticut, kind of way — not exactly Helen of Troy, but maybe Helen of Abercrombie & Fitch. (Think of her as the face that launched 1,000 golf carts.) She’s a limp presence, given to whimpering about all the trouble she’s caused as men die around her left and right. “All those widows! I still hear them screaming,” she intones feebly, without ever so much as dropping her nail file. (Contrast that with what Pauline Kael wrote of Irene Papas’ Helen in Michael Cacoyannis’ little-seen film “The Trojan Women”: “She is not merely a beauty but the strongest woman one has ever seen, and the more seductive because of her strength … She is not merely the cause of war, she is the spirit of war.”)

The other performers in “Troy” march around pompously, taking their roles very, very seriously. Banas’ Hector is dull and worthy, a lousy match for Pitt’s stiff, arrogant Achilles — you just wish they’d get on with it and kill each other, which is exactly the opposite of what Homer intended. Julie Christie appears very briefly as Achilles’ mother, the nymph Thetis, and her radiance warms up the movie for just a few minutes (although it stretches credulity that the point-and-grunt Achilles could have sprung from the flesh of anyone so luminously expressive). Elsewhere, Cox’s Agamemnon swans around in the kind of crazy-colored vestments favored by overweight middle-aged fiber artists, leaving half-chewed crumbs of scenery in his wake. At one point a character scolds, “You can’t have the whole world, Agamemnon. It’s too big — even for you.” But Cox gnaws so relentlessly at everything around him, you’re sure he could nibble it down to size in no time.

Sean Bean (who played Boromir in “The Fellowship of the Ring”) makes a serviceable Odysseus, and Saffron Burrows, as Hector’s wife, Andromache, captures at least some of the character’s innate sorrowfulness. But the only actor who is both certain of the baloney around him and stands resolutely above it is Peter O’Toole as King Priam, the father of Hector and Paris. (If you’re not familiar with the story, skip the next three paragraphs, which contain a spoiler — though since it is 3,000 years old, what, exactly, have you been spending your time on?)

After Achilles has killed Hector and dragged his body through the dust — retaliation for Hector’s earlier killing of Patroclus — he retreats to his tent to sulk and scowl. Priam strides into Achilles’ quarters, not caring that the disgruntled warrior is likely to kill him, too. He sinks to his knees before Achilles and kisses each of his hands. Then he looks up, his eyes so blue and clear they seem like portals to another world, and begs Achilles to give Hector’s body to him, so he can give his son a proper funeral.

Once you get past the notion of one of the great actors of the last half of the 20th century kneeling before someone as unworthy as Pitt, the scene is a revelation: O’Toole knows as well as anyone that good roles for an actor his age are few and far between. So in playing this one, he approaches it as if he were part of a prestigious stage production, and his line readings carve out an oasis of sanity in Petersen’s stultifying desert. “I loved my boy from the moment he opened his eyes to the moment you closed them,” Priam tells Achilles, the words soaked with so much raw feeling that Achilles barely knows how to respond to them. (Pitt, in return, adopts an air of simian confusion — he looks like Roddy McDowell in “Planet of the Apes,” although McDowell conveyed much more feeling, and channeled it through a lot more makeup.) O’Toole plays the moment as if “Troy” were a real Greek tragedy, and just briefly, the movie’s ridiculousness melts around him. His small but intense speech is the closest thing to a heart this movie has.

You could — and I’m sure people will — write reams on the ways in which “Troy” differs from its source material. I confess freely that my own experience with “The Iliad” is limited to the portions I read years ago in school and to the vivid explication of it found in Edith Hamilton’s “Mythology.” But revisiting excerpts of “The Iliad” recently, I was struck not just by how beautiful it is, but how readable. As Hamilton wrote of “The Iliad,” “it is written in a rich and subtle and beautiful language which must have had behind it centuries when men were striving to express themselves with clarity and beauty, an indisputable proof of civilization.” She goes on to remind us that we’re the descendants of the Greeks intellectually, artistically and politically. “The tales of Greek mythology … throw an abundance of light on what early Greeks were like … Nothing we learn about them is alien to ourselves.”

So what does Petersen’s retelling of “The Iliad” say about us as storytellers of the early 21st century — particularly at a time when we’re struggling with our own ideas of nobility in warfare, and perhaps questioning, as many have done before us, if there’s any nobility in it at all? I think we could forgive “Troy” for straying far from Homer if it at least told a story that moved or engaged us, if it didn’t seem so hell-bent on wowing us with its effects at the expense of its emotion, if its director, its writers and its actors had some sense of the tone of the original material, if not a line-by-line understanding of it. I’d be reasonably content if it even looked decent.

But “Troy” is just a booming extravagance with no lasting value. What will it look like to a civilization 3,000 years from now? It will tell them that American movies went through a dark period when all that mattered was to pack ’em in — when expressing oneself with clarity and beauty mattered far, far less than filling seats. How long this dark period lasts depends on what we demand from our filmmakers. Maybe it’s time to change the course of civilization as we know it.