The essence of romanticism, said the German writer E.T.A. Hoffman, is "infinite longing." With the marvelous "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban," J.K. Rowling's work has finally gotten the romantic filmmaker it deserves.

Rowling's series of books about a young orphan and wizard-in-training named Harry Potter -- "The Prisoner of Azkaban" is the third -- are nothing if not romantic works. Of their numerous intertwined themes, infinite longing rates pretty high: Harry's parents, a witch and a wizard, were killed when he was an infant, and he constantly wonders what they were like, and whether he's anything like them -- he longs to know. In the first book of the series, "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone," Harry glimpses them in a magic mirror, standing behind his reflection: "The Potters smiled and waved at Harry and he stared hungrily back at them, his hands pressed flat against the glass as though he was hoping to fall right through it and reach them. He had a powerful kind of ache inside him, half joy, half terrible sadness."

Director Alfonso Cuarón didn't get to dramatize that sequence: The movie versions of "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone" and of the second book, "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets," were both directed by Chris Columbus, who was doggedly faithful to Rowling's plots but singularly graceless in translating their syncopated lyricism to the screen. But "The Prisoner of Azkaban" is the first true Harry Potter movie -- the first to capture not only the books' sense of longing, but their understanding of the way magic underlies the mundane, instead of just prancing fancifully at a far remove from it. In the spirit of a true romantic, Cuarón knows that the secret to great fantasy is naturalism.

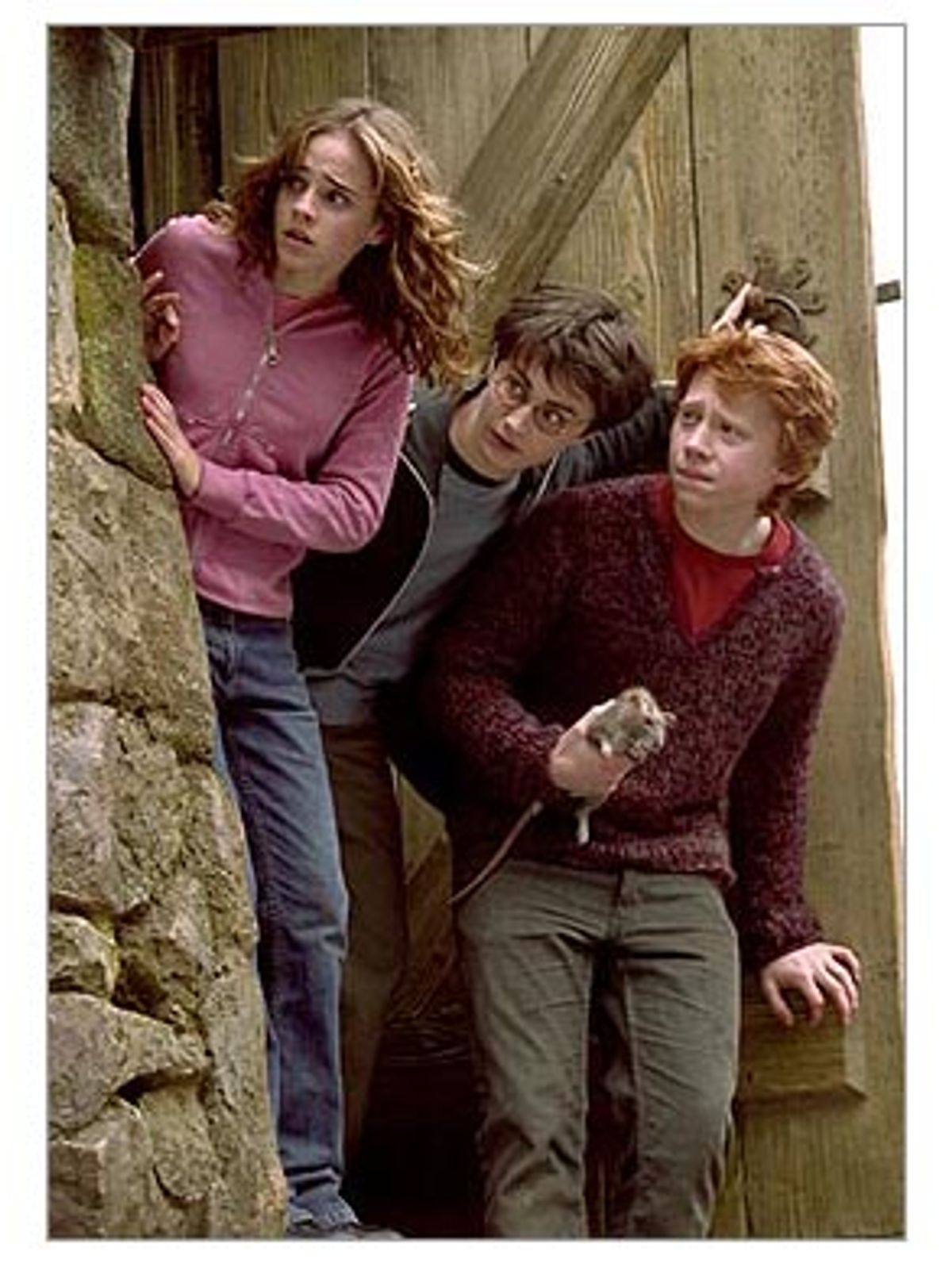

In "The Prisoner of Azkaban" 13-year-old Harry (Daniel Radcliffe), just before returning to Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry for his third year, learns that a dangerous wizard and mass murderer, Sirius Black (Gary Oldman), has broken out of Azkaban Prison, the Alcatraz of the wizard world. Black's picture appears -- moving, like a TV news clip -- in newspapers and "Wanted" posters; he has the unkempt, unhinged look of Charles Manson, his eyes gleaming maniacally. Worse yet, Harry hears that Sirius Black is responsible for the death of his parents and is now out to kill him. Harry and his fellow students at Hogwarts -- among them his best friends, Ron Weasley (Rupert Grint) and Hermione Granger (Emma Watson), as well as the trio's sworn enemy, Draco Malfoy (Tom Felton) -- are warned that until Sirius Black has been apprehended, the school will be guarded by horrifying hooded creatures known as Dementors, Azkaban guards who have the power not just to terrify their victims but to suck their very souls from them.

The Dementors seem to have a special interest in Harry: Before he even reaches the school, a Dementor confronts him, turning the air around him cold as ice -- Harry faints, causing some of his schoolmates to taunt him, and he himself questions his bravery. But the school's new Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher, professor Lupin (David Thewlis), understands why the Dementors have singled Harry out. He agrees to teach Harry how to fight them, so Harry will be freer to enjoy normal schoolboy pursuits like divination lessons and Quidditch matches. Lupin also has a link with Harry's past, which makes him particularly protective of the boy.

"The Prisoner of Azkaban" was adapted by Steven Kloves, who also wrote the screenplays for the first two Harry Potter movies. In this, as in the earlier scripts, he shows a good ear for Rowling's lively, unstuffy language. Hogwarts' headmaster professor Dumbledore, played wonderfully by Michael Gambon (stepping into the role previously played by the late, and truly great, Richard Harris), announces that the school's new Care of Magical Creatures instructor will be the beloved, gruff-and-gentle giant Hagrid (Robbie Coltrane). The former teacher, Dumbledore informs his charges, has "retired in order to enjoy more time with his remaining limbs" -- a direct quote from Rowling, and one that captures the mischievous flavor of her prose.

Kloves has also streamlined and sleekened the narrative, which Cuarón paces beautifully: It moves at a clip when it needs to, but it also flows gracefully when it should. And while Kloves and Cuarón may have lost a few crucial details (most notably an explanation of how Harry's father used to adopt the form of a certain animal), they've decanted the essence of Rowling's stories, at last allowing it to breathe on-screen.

Instead of feeling crammed with self-consciously clever details, as the early Potter pictures did, "The Prisoner of Azkaban" inspires a sense of wonder at even the smallest touches: Professor Lupin's classroom features tall, tapered candles that aren't just your typical spirals -- they're shaped like curvy human spinal columns, complete with individual vertebrae. The passing of time is denoted by a graceful pan of the countryside as Harry's white owl, Hedwig, flies across it: Its sun-tinted reds and oranges give way to the sparkling whites and grays of winter. The moving paintings that adorn the walls of Hogwarts have the dark richness of works by the old masters, even as the characters in them chatter and bicker and shuffle around. Cuarón and his cinematographer Michael Seresin even show us the texture of the paint, a surface of swirls and stippling that make these pictures look like real paintings-in-motion, and not just wowee special effects.

And all of the movie's characters, human and non-, seem finally at home in this extremely believable universe. The movie's loveliest creature is Hagrid's beloved Buckbeak, a hippogriff (that's a cross between a horse and an eagle, in case you didn't know), whose bright-eyed expressiveness is as mesmerizing as the swooping of his wings. The most terrifying figures are the Dementors, silent and virtually faceless specters that float in the sky, the tendrilly edges of their shrouds making them look like menacing, silky black squid. The Dementors rank among the most evocative horror images ever put on-screen: I wouldn't advise bringing a very young child to "The Prisoner of Azkaban," considering I'm not really sure I can keep the Dementors out of my own nightmares.

Although the previous Harry Potter movies have included some fine performances (from the likes of Harris and Kenneth Branagh, as well as from Coltrane, Alan Rickman and Maggie Smith, all three of whom reappear here), "The Prisoner of Azkaban" is the first Harry Potter movie that's really a showcase for actors. Radcliffe, Watson and Grint were appealing enough in the earlier movies, but their performances were also a bit stiff and perfunctory. Slightly older and more seasoned now -- in addition to the fact that they're working with an intuitive director who clearly knows how to guide young actors -- they've learned how to fully relax into their characters. They never mug; their faces show gradations of expression we haven't seen before. Emma Thompson is hilarious in her small role as the dotty, aged-hippie divination teacher professor Trelawny. And Oldman's Sirius Black and Thewlis' Lupin bring vast reserves of emotional gravity, balanced by the right proportions of good humor, to the picture.

Even before any critics or viewers had seen "The Prisoner of Azkaban," we all heard rumors of its "darker mood." "The Prisoner of Azkaban" is darker than any of the previous Harry Potters, in keeping with the tenor of Rowling's books. But the deeper undertones of "The Prisoner of Azkaban" feel organic -- they're not just pasted-on gloomy colors. Oldman and Thewlis, in particular, embody the picture's mood: There's shadowy complexity, as well as luminescence, in their hearts.

That's true of the overall look of the movie, as well, which I'm beginning to think is one of the most masterfully conceived and shot fantasy films of all time, precisely because it looks so un-fantastical. For one thing, despite the fact that "The Prisoner of Azkaban" shares many of the same sets as the earlier Harry Potter movies and, like them, was shot in the United Kingdom, it's the first Harry Potter movie that looks distinctively English. Columbus gave us lots of garish tones and busy bustle. But Cuarón -- who was born in Mexico City -- is highly attuned to that most quintessentially English characteristic: understatement.

Seresin clearly shares his sensibility. The colors of "The Prisoner of Azkaban" are muted and intense. Parts of the picture were shot in Scotland, and those sections set the movie's palette of smoky grays, misty browns and brilliant greens. These are the types of colors that don't reach out to us -- we need to come to them. And that's how "The Prisoner of Azkaban" works its most powerful magic: The picture is naturalistic without being aggressively pastoral. Set against such arrestingly realistic grays and browns, the sight of a hippogriff majestically flapping its giant, Pegasus-like wings looks more real than, say, a jet streaming across the sky.

Most movie audiences are familiar with Cuarón's last picture, the joyous and deservedly praised "Y Tu Mamá También." That movie's success may have led some viewers to seek out Cuarón's first American feature, the 1995 "A Little Princess," an adaptation of Frances Hodgson Burnett's Victorian children's story and, for my money, one of the most lush and emotionally resonant children's films ever made. Cuarón's 1998 adaptation of "Great Expectations" has far fewer defenders, but I adore it, and, in the context of this new Harry Potter movie, I urge people who may have dismissed it to have another look. If nothing else, the verdant romanticism of "Great Expectations" points the way to "The Prisoner of Azkaban."

Cuarón has the eye of a landscape painter and the heart of a humanist. The killer twist is that he's also an extraordinarily gifted storyteller. Rowling is reportedly a big fan of "A Little Princess." It's fitting that Cuarón is the filmmaker to at last give her writing the on-screen life it deserves. I often think of great movie adaptations not just as extracurricular versions of the books they represent but as vital accessories to those books -- compact but substantive ghosts that sit on the shelves among and between the pages, huddled up close, guardians of their elusive yet sturdy spirits. As an adaptation, "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban" is all you could wish for. It has earned its place on the bookshelf.

Shares