Early in Steven Spielberg's "The Terminal" an immigration officer at JFK Airport in New York announces, "America is closed." How can an American movie with that line at this time provoke ... nothing? Not self-righteous applause, not hissing or booing. Nothing. The answer is when it's as blandly inoffensive as this picture.

"The Terminal," written by Sacha Gervasi and Jeff Nathanson from a story by Gervasi and Andrew Niccol (the writer of "The Truman Show"), recalls nothing so much as the artifacts of counterculture absurdist whimsy that were all over movie screens in the '60s and '70s. That perennial double-bill "King of Hearts" and "Harold and Maude" were two of the most popular. These were movies where the officials in charge were boobs and incompetents with a fetish for regulation and procedure. Their opposites were either rebellious free spirits or, more frequently, holy innocents who inadvertently roused the ire of the powerful. These movies offered the counterculture the fairy tale that their pure hearts would eventually defeat the forces of conformity and war and capitalism lined up against them. In other words, in the guise of making a political statement, they substituted kookiness and treacle for politics.

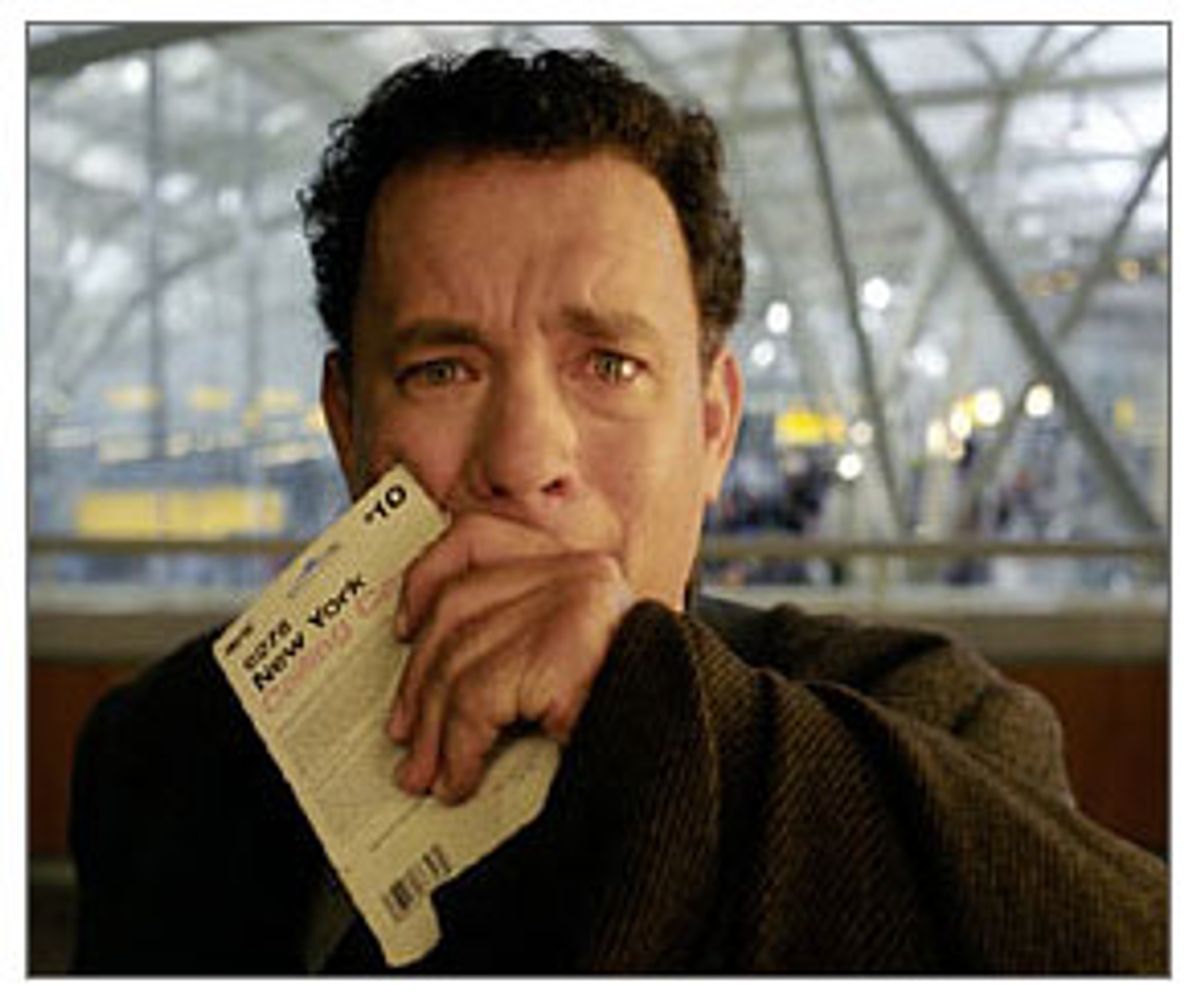

There is a difference between movies that avoid politics because they recognize that the divisions of politics -- or at least the way those divisions are employed -- usually end up diminishing art, and movies that soft-pedal the politics they raise for fear of alienating somebody. "The Terminal" belongs to the latter group. This story of a man (Tom Hanks) who gets stuck for months in the international lounge at JFK because of a bureaucratic Catch-22 must have struck Spielberg as a way to say that America's current suspicion toward foreigners is contrary to the American way without venturing into any of the messy questions the new restrictions on entering the country raise. (When Floyd Abrams, the country's most noted First Amendment lawyer, speaks in favor of racial profiling at airports, things are not breaking down along traditional left-right lines.)

Hanks plays Viktor Navorski. While he's en route to New York, the government of his Eastern European country is toppled in a coup. By the time he lands at JFK, his country is controlled by rebels not recognized by the U.S. government. Denied entry to America, he is unable to return home, and unable to go through the terminal doors and hail a cab for Manhattan. So Viktor becomes a resident of the international terminal, shuttling to the men's room in his bathrobe, returning luggage carts for spare change in order to eat, picking up bits of English from guide books he browses at the airport Borders or from looking at CNN, forming friendships with the airport workers he sees every day, and beginning a flirtatious dance with Amelia (Catherine Zeta-Jones), the flight attendant he keeps running into.

Here's what you have to believe if that premise is going to work. In the international lounge of one of the world's busiest airports, Viktor wouldn't encounter any travelers who speak his language (unlikely, since the movie shows him making himself understood to a man from a neighboring country). You have to believe no one would hear Viktor's story and help him contact someone who could come to his aid. You'd have to believe that the press wouldn't get wind of Viktor's predicament sooner or later and turn it into an embarrassing piece of publicity for the U.S. government.

Here's how "The Terminal" wants you to believe it: the perfidy of the U.S. government. In the movie's scheme, Dixon, the head of airport security (Stanley Tucci) is in line for a promotion and fears calling attention to any problem that might jeopardize it. A single moment of rationality should have told Spielberg and his screenwriters that Viktor is much more of a threat to Dixon's promotion while he's wandering around loose. If he's the security risk Dixon sometimes suspects he is (Dixon is obsessed with finding out what's in the can of Planter's nuts Viktor guards with his life -- it's a lot less interesting that Dixon imagines), then Dixon can only hurt his career by not interrogating him. If Viktor is just a poor sap stuck in a bureaucratic no man's land, Dixon's failure to provide him with a translator or food or traveler's aid means the story could easily get out for someone else to spin. From there Dixon could kiss his promotion goodbye.

But if the American government's hostility toward foreigners is an article of faith for you, then it doesn't matter how implausible "The Terminal" is. And the recent deluge of depressing news -- not just the horrors at Abu Ghraib but the stories of people picked up and held on the flimsiest of suspicions -- are, for some, going to make the movie a "relevant" experience. As a liberal, I'd like to believe that liberals aren't going to be gullible enough to swallow a movie so blatantly tailored to their prejudices. But I've seen worse movies than "The Terminal" acclaimed for their courage and daring.

Stanley Tucci's performance is designed to flatter those prejudices. He's playing an ambitious, rigid, tightly held-in man, a man who can't think of any other way to do things than by the book. But he doesn't show us the fear that might have humanized this putz. Throughout the movie, walking around the airport or even just sitting at his desk, Tucci leads with his balding head. Are we to intuit from the emphasis Tucci puts on his gleaming pate that he's playing a walking hard-on? The situations devised to show what a meanie Dixon is are shameless: He denies a man medicine to take back to his dying father; he threatens to deport foreign airport workers. Tucci doesn't have the sense of restraint to underplay these situations (or, rather, his underplaying is a form of overplaying). If Spielberg had given Tucci a chance to kick a dog to show what a bastard Dixon is, he'd have seized it.

In Spielberg's view, Dixon represents the un-American American, and the people who come to befriend Viktor -- the airport workers -- are the melting pot that prove him wrong. Spielberg doesn't find a way to make that melting pot funny, the way Paul Mazursky did in "Moscow on the Hudson." Worse, you can't make a movie about the way foreign people are made invisible in America when you're using the foreign actors in your movie as little more than ads for brotherhood, the way they were used in that old Coke commercial. (Next to the way Alfonso Cuarón unshowily includes so many nonwhite faces in "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban," Spielberg's method is embarrassingly obvious.)

I was happy to see big Chi McBride (who always makes me laugh) as a baggage handler. And Kumar Pallana, as an Indian janitor, gets the movie's biggest laughs, juggling rings and spinning plates in the back of one shot (for a moment, it's as if a rerun of "The Ed Sullivan Show" has taken over the movie). But they merely pass through the movie, and so do Diego Luna, as a food-service worker, and Zoe Saldana, as the immigration officer he worships from afar. Saldana is a slim beauty who always looks as if she's two steps ahead of everyone else (I retain a happy memory of her in "Center Stage," using the point of her ballet toeshoe to grind out a cigarette), and Luna wears a dashing mustache that's very touching because his face is too young to pull it off (you can imagine the character keeping that mustache for 50 years and growing into it). Luna asks Hanks' Viktor to find out information about what Saldana likes so he can woo her. But in their very first scene together, he offers her an engagement ring and in the next scene they're hitched. How lazy does a movie have to be to spend scene after scene setting up a romance and then deny us the pleasure of watching the couple court? Even being utterly charming doesn't get Luna and Saldana any more screen time.

But then, apart from the scenes between Roy Scheider and Laraine Gray in "Jaws," I've never been convinced that Steven Spielberg understands anything about male-female relationships. His last movie, "Catch Me If You Can," featured an odd, ugly sequence where Leonardo DiCaprio cheated Jennifer Garner, as a call girl, out of her fee. It felt like Spielberg threw in the con to take our minds off the possibility that his hero might have enjoyed going to bed with a prostitute. And the fact that she was a prostitute was supposed to make it OK that he robs her. The scene felt like the product of a particularly inhibited 13-year-old male mind.

The scenes in "The Terminal" between Hanks and Catherine Zeta-Jones are meant to twinkle with romantic possibilities. They're forever trying to find a way to get a meal together -- and that's about what they suggest, a pair of people destined to share a very pleasant lunch. There's no chemistry between them, unless sexlessness is Spielberg's idea of romance. And it might just be. CZJ's Amelia is having an unsatisfying affair with a married pilot (Michael Nouri). Viktor is the man she's able to pour out her heart to. Doesn't Spielberg know that when a woman puts a man in that position, she's implicitly or explicitly telling him she isn't interested in him romantically? Zeta-Jones is, as usual, easy on the eyes, and she's light and appealing. But the role is incoherent. When was the last time you saw a contemporary woman deliver a "Stay away from me -- I'm bad news" speech? Did Steven Spielberg get his ideas about women from Susan Hayward movies? And there is no consistent thread through her character. One minute she's defending Viktor to Dixon and in the very next scene berating Viktor for not telling her the whole truth of his situation. Zeta-Jones is too sexy, too beautiful and too sharp to get stuck playing a pixified ditz.

In Tom Hanks' last movie, the remake of "The Ladykillers," he played a role spun off of Alec Guinness' in the original. Here he's in a role that only Alec Guinness could have played (or maybe Peter Sellers). Guinness had a way of finding a flinty, obsessive edge inside his dreamy, gentle eccentrics, a way of making them seem more exotic bird than cuddly pet. Some of what Hanks does -- the silly stuff -- is fine, particularly one moment when his accent makes it appear he's cursing out Luna. But Hanks and Spielberg have conceived of the role as a dear, harmless little foreigner, the Esperanto Everyman. Even Chaplin's Little Tramp, in the early two-reelers, had some dirt and salaciousness in him. Viktor, however, is the simple villager unsullied by American reality and still enough of an innocent to believe in American ideals. Before anyone believes in "The Terminal" as a take on American xenophobia, they should think about its emasculated mascot of a hero.

"The Terminal" might have worked if it had been conceived of as the equivalent of an Ealing comedy, or if the Scottish director Bill Forsyth had had a crack at it. It would have meant cutting all the politics out and just making it about a man making do in an absurd position. (It would have been possible to make this movie and show the airport officials acting decently toward him). But that approach wouldn't allow Spielberg the lumpy e pluribus unum message he's waving around here. And as a filmmaker he seems to have lost the simplicity necessary for such an approach.

"The Terminal" is probably the worst-directed film Spielberg has ever made. A peculiarly rhythmless piece of work, it seems to go on forever, though nearly every one of the scenes is cut off before it has been dramatically developed. Or else it's shot and edited in a jumpy style that makes you feel as if you can't settle down to pay attention to what's going on. I'd like to give cinematographer Janusz Kaminski the benefit of the doubt and assume that the movie looks so blah because he's trying to capture the fluorescent, washed-out lighting of an airport terminal. Even if that's what Kaminski intends, it means we're stuck looking at these drab visuals for two hours.

Is "The Terminal" Steven Spielberg's idea of taking a break from the prestige message pictures his career has come to consist of? If it is, then he hasn't taken enough of a break. He's got an idea here for a quirky, small-scale comedy. But giving it the modest scale it needs wouldn't make it important enough to suit him. Cutting out all the rather brainless political content would make it a mere entertainment. So he has proceeded in a style and tone utterly inappropriate to the material. Is every script Spielberg attempts from now on going to have to be worked up to be worthy of him? His hero isn't the only guy stuck in no man's land.

Shares