"I, Robot" is set in Chicago circa 2035, a land of silver-and-granite skyscrapers that stare coldly at the world through monster-size safety-glass eyes. The movie itself is a cold, blank stare, and it's skyscraperish itself, always aware of its massive size and its state-of-the-art sleekness -- it has an edifice complex. Part whodunit, part action film, part chilly cautionary tale (don't think you're going to escape from its clutches without the obligatory "We must save humanity from itself" scene), "I, Robot" strives to be so many things that it ultimately falls away to nothing, a heap of expensive metal parts.

Through occasional sections of the movie, those parts hang together well enough to make you think they actually serve a useful, entertaining purpose: In places I found myself drawn in by "I, Robot," but usually with the sharp clang of magnet to metal. If I responded to the picture in any remotely organic way, that had to do mostly, I think, with Will Smith.

Smith plays Detective Del Spooner with his usual affable touch, and we're eased into this dry, metallic movie with an early scene, set in his laid-back, '90s-style apartment, in which he awakens, rises seminude from his bed like a magnificent dolphin god, and steps into the shower, where the water flows off his torso in a rushing S-curve. For human beings of all genders and persuasions who are inclined to enjoy looking at the human body, this vision is both potently erotic and lyrically earthbound -- it's everything in the movie that's really worth looking at, and after the first 10 minutes of the picture, it's over.

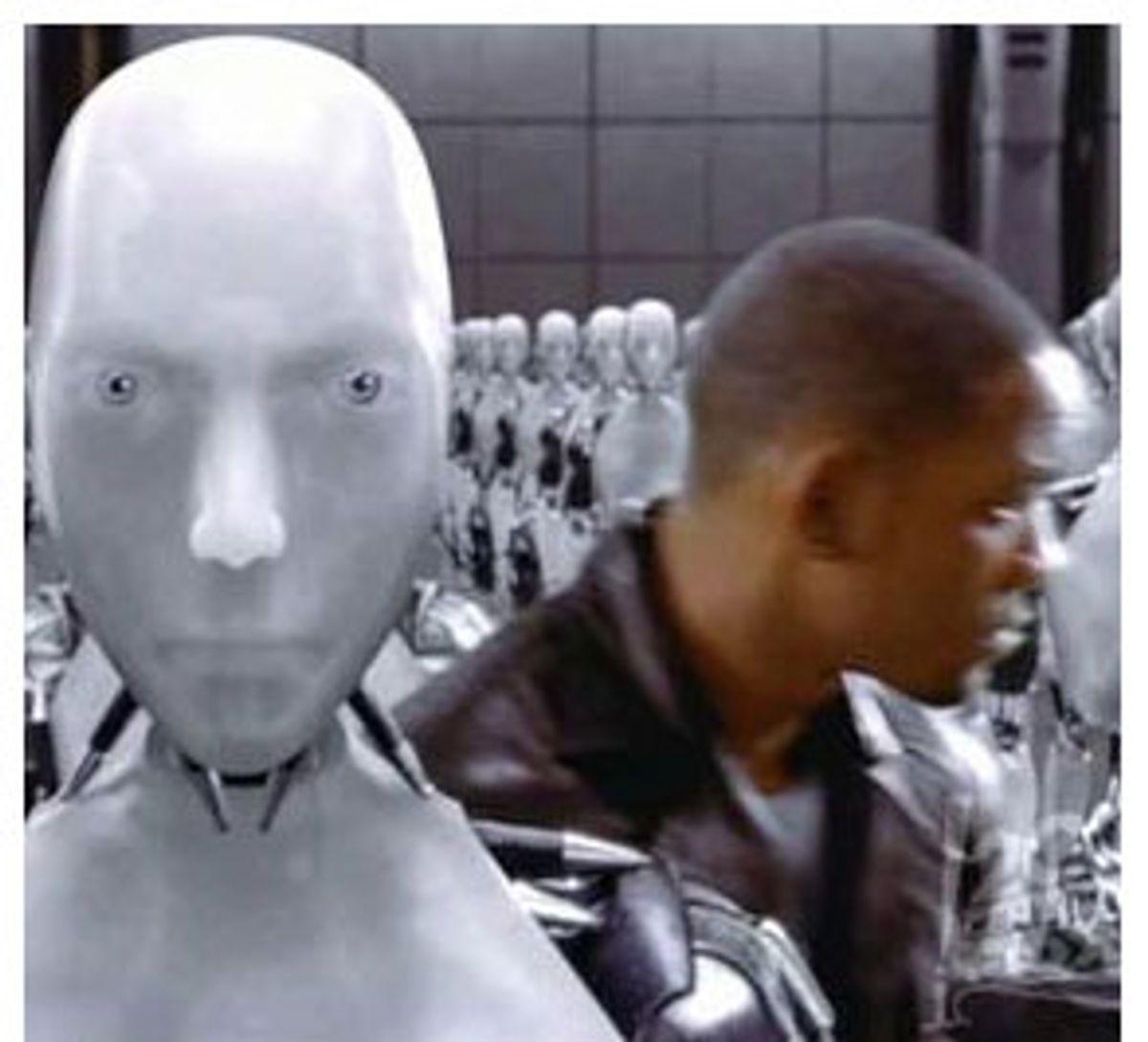

Spooner lives in a world of robots -- they walk among humans, mechanical servants built only to serve and never to harm -- but he deeply distrusts them, in part because of a guilty secret he harbors. And we grasp early on that Spooner, whose body looks like a Michelangelo sketch conceived in muscular inverted triangles, bears a notable resemblance to the robots around him: They, too, sport slender hips and chests that flare out like pilsner glasses -- although unlike Spooner, who has a loose, easy gait, they strut elegantly, if stiffly, on their pegged-together legs.

But those are the old-fangled, pre-2035 robots we're talking about. The fellow who got the whole robot biz started in the first place, Dr. Alfred Lanning (James Cromwell), is about to introduce a far more advanced and somewhat more human type of robot, the NS-5 (and in vast, armylike quantities to boot). On the eve of the big robot launch, he mysteriously commits suicide; Spooner is assigned to the case, and immediately smells something fishy in robotland. The sylphlike Dr. Susan Calvin (Bridget Moynahan), a specialist in robot pyschology, reassures him that the new, improved robots, as the old ones were, are programmed to strictly follow orders and would never harm a human. But one NS-5 in particular, the very special Sonny (a computer-generated character whose movements and mannerisms were adapted from those of actor Alan Tudyk, Gollum-style), suggests to both Dr. Calvin and Spooner that these new mechanical creatures may be more dangerous than anyone realizes.

You can hear the gears groan mightily as director Alex Proyas ("The Crow," "Dark City") manipulates the man-vs.-machine theme with giant mechanical fingers. In between, there's the requisite amount of action, including a car-chase scene (it's actually more of a car-vs.-robot scene) that takes place in a tunnel, with loads of clanging bangs and crashes and lots of metal-against-metal sparks.

And so what? Even with its grand "Oh, the humanity!" themes ringing so loudly throughout, "I, Robot" feels cavernously empty. Its production values are high, if height is what you're after, and the eerie expressiveness of the NS-5s is weirdly riveting, at least at first. (The "flesh" that covers their faces and parts of their smoothly mechanized bodies has a pearly, rubbery glow, like the protective pliable cases made for iPods.)

But once you've been wowed by the production values and computer imagery of "I, Robot," there's not much to gawk at. And the hint of romance that's stirred up between Spooner and Dr. Calvin never amounts to anything (apparently, that weary old "fear of interracial romance" thing once again rears its tired head). The script, by Jeff Vintar and Avika Goldsman, borrows daintily here and there from the classic Isaac Asimov stories from which the movie takes its title. It just doesn't feel like Asimov -- not even like an incredible simulation of Asimov. It is, like the NS-5 itself, remarkably lifelike. But aside from Smith, there's just too little life to like.

Shares