In “Hotel Rwanda” it’s a few days into the 1994 genocide in which the majority Hutu tribe would eventually slaughter nearly a million of their Tutsi countrymen with no interference from the West. Refugees have holed up at the Mille Collines luxury hotel in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, waiting for the international intervention forces they expect to protect them from the marauding Hutus. Colonel Oliver (Nick Nolte), who’s in charge of the U.N. peacekeeping forces, greets the arriving international troops with relief that, in just a few seconds, turns to disgust.

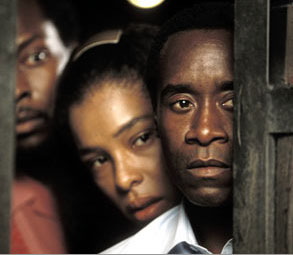

Following Oliver into the hotel bar, the manager of the Mille Collines, Paul Rusesabagina (Don Cheadle), congratulates the colonel on how well he has protected the refugees while awaiting the international forces. What Paul doesn’t know, and what Colonel Oliver has to break to him, is that the forces are there only to provide safe passage out of Rwanda for Europeans. They will do nothing to stop the slaughter or aid the Tutsis. The scene that follows between Cheadle and Nolte is so emotionally violent that it takes you a few seconds to register that you’re hearing what you’re hearing.

“You should spit in my face,” says Colonel Oliver to Paul. “You’re dirt. We think you’re dirt, Paul … The West, all the superpowers … They think you’re dirt. They think you’re dung … You’re not even a nigger. You’re African.”

It’s a shocking moment (did Nolte just tell Cheadle he’s “not even a nigger”?), one that punches out its meaning in the bold typeface style of a tabloid headline. There’s nothing artful about it, and yet it contains the heart of this shattering movie.

A startlingly effective and upsetting political melodrama, “Hotel Rwanda” — which is based on a true story and was directed by a Westerner, Irish filmmaker Terry George, who cowrote the film with Keir Pearson — is out to rub the West’s nose in its refusal to intercede in stopping the genocide. And George and Pearson want to deprive us of the subsequent easy out of conceding that we sure did act terribly toward the Tutsis. Every time we see a Hutu bringing a machete down on the body of a Tutsi (and it should be said here that the film, rated PG-13, depicts the slaughter by suggestion), the movie wants us to think, “We allowed this to happen.”

If that makes “Hotel Rwanda” sound like a bullying or self-righteous movie, it isn’t. In spirit and technique, it’s close to the muckraking films that Warner Bros. turned out in the early ’30s, hard-edged pictures like “I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang” that aimed to shake up audiences’ sense of justice and moral outrage.

It’s not a pure film. George, who directed the terrific “Some Mother’s Son,” about the group of IRA hunger strikers that included Bobby Sands, uses the techniques of suspense movies here to work you over. (I was shaking when I left the theater.) At moments, particularly in a sequence involving a confrontation between Hutu killers and U.N. soldiers conveying a group of refugees to safety, “Hotel Rwanda” comes close to the tension of the sequence in the first “Godfather” film in which Al Pacino’s Michael first commits murder. You watch it with your heart slamming against your rib cage.

Cheadle’s Paul, a Hutu who has three children with his smart, gutsy Tutsi wife, Tatiana (Sophie Okonedo, who makes you feel as if each horror she witnesses etches a line on her face), has learned the key to being a success in his job managing the Mille Collines. Through a combination of glad-handing and bribes, he flatters the military and political big shots who frequent the hotel, and makes sure the place has the food and booze it needs to keep its upscale customers happy.

There’s nothing phony about Paul. The pride he takes in doing his job well is really pride in fulfilling his obligation to care for his family. In the course of “Hotel Rwanda,” Paul’s conception of family expands considerably. The real Paul Rusesabagina managed to shelter and keep alive more than 1,200 people in the Mille Collines during the 100 or so days of the genocide. “Hotel Rwanda” shows how Paul uses the skills of his job to save the lives of his family and neighbors and others, like the children a Red Cross worker (Cara Seymour) drops off at the hotel. At one point, Paul worries that all the refugees he is allowing to stay in the hotel will cost him his job. It’s not his bravest moment, or his finest, but it’s his most human. Paul cannot make the terrifying leap of realizing that everyday life as he knew it is over. “Hotel Rwanda” is about how he makes that leap without renouncing his decency. It’s about how you remain a human being while the life around you is drowning in derangement.

The film is, unbelievably, Cheadle’s first starring role, and it’s his triumph. Cheadle plays a good man without turning him into a saint or making his bravery falsely noble, perhaps because he never divorces that bravery from an edge of desperate cunning. Cheadle is one of the few actors capable of making you believe that you are seeing him thinking. There is a way, when the solution to a problem appears to him, that he lifts his head and moves his eyes from side to side that makes you feel he has been following a slender thread through a nest of tangles and seen his way clear. That’s why the moment when he loses his composure, a wordless panic in which this meticulous man cannot tie his tie, is so unnerving. Cheadle gives an intensely charismatic performance and one of the quietest, most modest portrayals of heroism in memory.

Terry George’s refusal to show us the details of the slaughter is not squeamishness. It’s the simple realization that there are some events so immense they can be depicted only in discrete pieces. The killings are suggested to us in quick cuts, often in long shots, and by images like a Hutu killer throwing down the empty helmet of a U.N. soldier (the Hutus killed 10 Belgian U.N. soldiers); Paul frantically cleaning blood off his young son and realizing, to his relief and horror, that it is not the boy’s blood; a fleeting, surreal shot, glimpsed from a passing car, of the bodies of a murdered Tutsi family lying on their manicured suburban lawn.

What the movie is saying is not suggested but bluntly, forcefully stated. Deeply humane, “Hotel Rwanda” is nonetheless not a humanist movie. In an early scene, a Rwandan tries to explain to a visiting journalist (Joaquin Phoenix, who’s so fresh he makes you feel that no one has ever played the part of a cynical reporter shocked into humanity by the events unfolding around him) the origins of the hatred the Hutus feel for the Tutsis. He explains that when the Belgians ran the country, they praised the Tutsis as more elegant, but perversely put the Hutus in charge when they left. It’s an attempt to sketch in a bit of history, and it feels as if we’re meant to reject it in the same way we reject the psychiatrist’s explanation at the end of “Psycho.”

In “Terror and Liberalism” Paul Berman points out that the left, steeped in the Rousseauist principles of enlightenment, has had trouble crediting the irrational, even when the irrational is embodied in the fascist movements the left has traditionally opposed. George and Pearson understand that no explanation can ever fully account for an outbreak of the irrational on as massive a level as the Rwandan genocide. In essence, they are saying that evil took over in Rwanda.

You feel that evil in the movie’s opening. We stare at a black screen while we hear the sound of one of the radio broadcasts that stirred the Hutus to murder. As seductive and repellent as a serpent in the garden, the Hutu announcer tells his listeners that their Tutsi neighbors are traitors and instructs them to “stay alert.” By the time Paul is driving home in the dark and ominous, unintelligible murmurs are weaving in and out of the static on the radio, it’s as if the country is in thrall to a force that is whispering poison directly into its brain.

This is not a subtle or nuanced view. But to want something subtle or nuanced in a film made to show the shame of a genocide that could have been prevented is to say that aesthetics should trump moral urgency. It’s to invoke “culture” — a quality the West did not embody in its abandonment of the Tutsis — as one more way to insulate ourselves from our culpability in the Rwandan genocide.

Which is why that speech of Nolte’s contains so much of the essence of “Hotel Rwanda.” It makes perfect dramatic sense that the colonel, a soldier frustrated by the idiot orders that designated U.N. soldiers “peacekeepers” but prevented them from doing anything that might actually bring about an end to the killing (this is not a pacifist film), would speak in exactly those disgusted tones. (It’s the disgust you find in “Shake Hands With the Devil,” the memoir by the man who is the basis for Nolte’s character, Lt. Gen. Roméo Dallaire, who was the commander of the U.N. forces in Rwanda.)

The lines make even more sense when you compare them with the words being said at the time by American officials in response to the genocide, words you can find in the excoriating section on Rwanda in Samantha Power’s “‘A Problem From Hell’: America and the Age of Genocide.” Prudence Bushnell, then deputy assistant secretary of state in the Clinton administration, remembers being told, “Look, Pru, these people do this from time to time.” After the evacuation of foreign nationals, Sen. Bob Dole said, “I don’t think we have any national interest there. The Americans are out, and as far as I’m concerned, in Rwanda, that ought to be it.” The Clinton administration consistently opposed use of the word “genocide,” and a position paper from the secretary of defense’s office warned, “Be careful … Genocide finding could commit [the U.S. government] to actually ‘do something.'” “Hotel Rwanda” lets us hear the actual exchange between State Department shill Christine Shelly and Reuters reporter Alan Elsner when Shelly said that “acts of genocide” were taking place in Rwanda but, despite Elsner’s attempts to pin her down, insisted that she could not claim those acts constituted “genocide.”

George and Pearson have taken the full moral measure of those weaselly public utterances and dozens of others and stripped away the euphemism and self-justification the West employed in its refusal to stop the Rwandan genocide. Instead of the politesse of “these people,” we get “niggers.” Instead of the couched bureaucratic platitude “I don’t think we have any national interest there,” we get “They think you’re dirt.” If Nolte’s character responded any less fiercely, “Hotel Rwanda” would have slid into the very squeamishness it’s exposing, and the result would have been as aesthetically and morally grotesque as if, in “Bonnie and Clyde,” Arthur Penn had decided to cut away from the violence.

“Hotel Rwanda” is a terrific example of what movies can do when they seize real events as raw material and are made by people who are passionate and canny, who know just how far they can squeeze us without turning crass or exploitative. It’s as good a political melodrama as anyone has made since “Z.” The movies offer us so little connection to real life (even to the point of denying the recognizable human emotion that has always been present in the greatest entertainments) that “Hotel Rwanda” feels meaty in a way we’re no longer used to. It’s also the kind of movie that, because it does not advance “the art of the film” (God help us), may be ignored by some critics who prize aestheticism above all else. It may be a terribly extreme thing to say, but I don’t think I could ever look at anyone who didn’t feel something at this movie — who dismissed it because of aesthetic flaws or the awkwardness of some of the dialogue — and believe he or she was fully human. We know how little attention the West paid to the Rwandan genocide as it was occurring. The question now is, How much attention will be paid to this movie?