The idea of a high school basketball coach who benches the whole team for getting lousy grades -- as real-life coach Ken Carter, of Richmond, Calif., did in the late '90s -- sounds like a dream come true for manly-man cultural conservatives, the sort who like to grumble that the misguided youth of America just need a little discipline, dammit.

But even though schoolwork should take precedence over sports for student athletes, all that bullying pulpit-thumping is more of a turnoff for kids (and for plenty of grown-ups) than schoolwork itself. What's more, while the Ken Carters of the world really do make a difference, in their communities and beyond, once they're turned into movie subjects they usually come off as deadeningly square -- like walking public service announcements for that maddeningly vague yet undeniably important concept known as self-esteem.

And yet somehow "Coach Carter," which is based on the story of Ken Carter, avoids that trap. The movie has problems: At some two hours and 15 minutes long, it not only belabors some of its points but tacks on a few extra ones just for good measure. This isn't a ponderous movie, but its sheer length sometimes makes it feel like one -- it would pack more of a wallop if it were shorter and sharper. But "Coach Carter" is also one of those highly effective conventional pictures that remind us that conventionality isn't always a bad thing. There's a reason the "To Sir With Love"-style role-model picture has become a fixture; even when we know these movies are bad, we often feel stirred by them.

"Coach Carter" contains all the usual ingredients of such pictures (including at least one "pull yourself up by the bootstraps" speech, a requirement of the genre), but it's also intelligent and scrappy. What's more, Carter's treatment of social issues -- not least among them that eternal hot button, teen pregnancy -- is more progressive than anything I've seen at the movies in years. In that respect, "Coach Carter," a picture straight outta Hollywood, puts smug, cutesy little indies like "Saved" to shame.

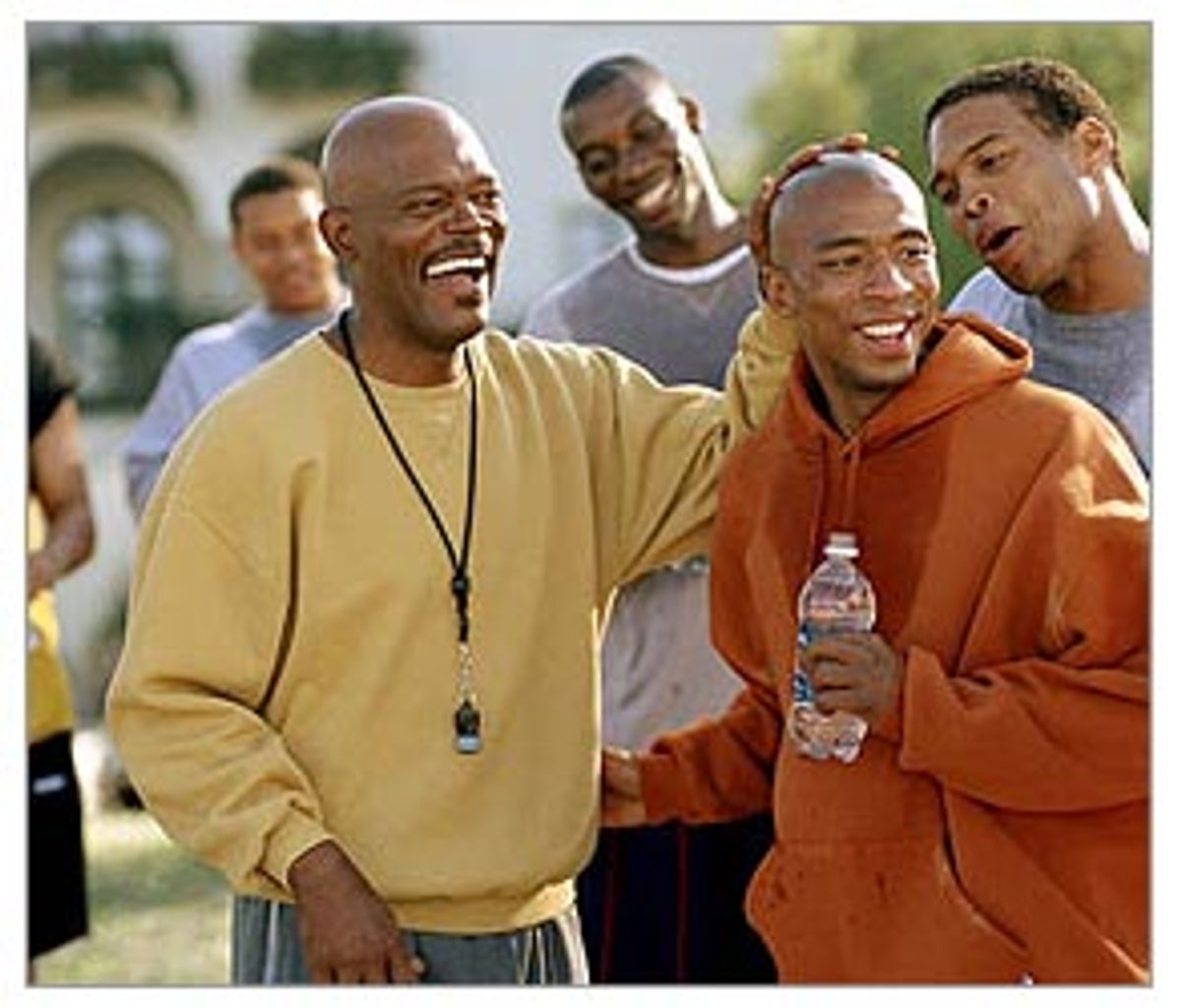

Carter is played by Samuel L. Jackson, who seems well aware of the dangers of playing a role model: Instead of trying to defy the stereotype, he plays into it for its entertainment value. Carter, a successful businessman who owns several sporting-goods stores and is never seen in anything but gorgeously tailored suits, is an alumnus of Richmond High School, a down-at-the-heels city public school with a high dropout rate. A former star basketball player for the school, he has been lured back to coach its current team, a job that requires long hours for not much pay. The first day he faces his team -- a racially mixed but largely African-American group of kids who, of course, immediately begin testing him -- he stares them down with a glare in his eyes that's almost as fierce as the gleam of his elegantly shaved pate: "If practice starts at 3, you're late at 2:55." Coach Carter's ass is clearly as hard as his head.

Even so, there's something a little mischievous about Jackson's drill sergeant bit. He takes the role of Carter seriously without taking himself seriously, which is perhaps the key to playing this kind of character without making him insufferable. And so even though you'll be able to guess ahead of time most of what happens in "Coach Carter," there's still pleasure to be had in watching the way Jackson interacts with the younger actors (among them Antwon Tanner as "Worm," an incorrigibly charming cutup who's a hit with the ladies, and Rob Brown, who played the young writer in "Finding Forrester," who gives a fine performance here). Coach Carter takes some tacks that are predictable (like lecturing the guys on why they shouldn't use the term "nigga") and others that are less so: While he expects them to address him as "sir," he also insists on addressing each of them as "sir" -- because, as he explains, "'sir' is a term of respect, and you will have my respect until you lose it."

At the start of his tenure as coach, Carter makes each kid on the team sign a contract, promising that he'll maintain at minimum a 2.3 grade-point average (and also that he'll wear a jacket and tie to school on game days). And when, predictably, several of the players dip below that average, Carter keeps his word and locks the gym, jeopardizing the team's extremely good chances at winning the state championship -- they can't win if they can't play.

Oddly enough -- or, perhaps, not oddly at all -- some of the teachers (and even the school's principal, played with scary authority by Denise Dowse) are rankled by Carter's methods, partly because they feel his high standards reflect badly on them and partly because they realize that basketball is the only thing some of these kids have in their lives. But Carter is adamant: He sees decent grades as a way of surviving life beyond high school basketball, as well as a way for his top players to earn scholarships.

If that sounds like basic common sense, it's worth highlighting the difference between this movie and last year's "Friday Night Lights," in which high school football players in a no-future West Texas town desperately hope that football will get them out. In that town, the allegedly grown-up citizens fetishize their high school football so much, they've diverted money away from the school to build a fancy stadium for the kids to play it in; they pin all their own hopes and dreams on these kids to the point of dementia, wanting them to reflect glory back on their town. And yet the director, Peter Berg, points his camera at this depressing situation with a blank gaze. His movie imparts a very valuable lesson (the one that begins, "It's not whether you win or lose" -- and I'll spare you the rest) without squarely addressing the bigger problem that in order for most kids to get anywhere, it's a good idea for them to actually go to school, whether they're wonderful athletes or not. The movie's refusal to state the obvious is a bald copout.

"Friday Night Lights" sprawls all over the place, while "Coach Carter" is direct to the point of utter predictability. Even so, its unvarnished good sense is more refreshing than it is tedious. The director, Thomas Carter (no relation to Ken), also made the supremely entertaining, and very canny, teen interracial romance "Save the Last Dance." (Carter got his start directing episodes of "The White Shadow," about a white former NBA star coaching in an inner-city public school, in the late '70s.)

Carter and the movie's screenwriters, Mark Schwahn and John Gatins, know what they're doing: Some of the kids in "Coach Carter" may be headed for trouble (one, in particular, played by Rick Gonzalez, is dealing drugs on the side), but Carter doesn't go out of his way to present them as stubborn or disengaged just so he can heighten their eventual transformation. They seem like decent, likable kids from the start, which immediately heightens our own desire to see them succeed. The picture never takes that hectoring, good white liberal tone of "Now, these young men may seem like animals, but they're really diamonds in the rough." Carter accepts their worthiness as a given at the start.

But then, "Coach Carter," its flaws aside, is as interesting for what it doesn't do as for what it does. Instead of cluck-clucking over the prevalence of inner-city teen pregnancy, the movie acknowledges it as a reality, without exactly condoning it. When Kyra (played with flirty, self-assured charm by pop singer Ashanti) meets her boyfriend, Kenyon (Brown), one of the team's star players, at the local burger joint and dangles a pair of baby booties in his face, her excitement over the impending birth of the couple's baby is clear. But Kenyon, who loves Kyra and wants to be with her, but who is also secretly hoping to play college ball and build a better life for himself than that of most of the people in his community, begins questioning the path the couple are headed on: He realizes he'll need to work to support the baby, and Kyra will too. As a young mom, will she be able to attend junior college? Does she care?

Kenyon wants Kyra to answer those questions for her sake as well as his because he's a thoughtful kid and not just a useful stereotype. ("Coach Carter" may be conventional, but it doesn't stoop to the dramatic cliché of depicting a black man's skipping out on his girlfriend and kid.) To fully explain what's most remarkable about "Coach Carter" would require revealing a few key plot details. But I don't think it's giving too much away to note that unlike "Saved," in which a white Christian teenager becomes a mom without ever asking aloud, "How will I support this baby? How will my life change?" "Coach Carter" treats the issue of teenage pregnancy with a gravity that is, in this climate of restrictiveness about the way we discuss such issues, frankly shocking. "Coach Carter" is a movie about kids made by a grown-up. Because, sometimes, somebody has to play the authority figure, if only to be the voice of reason.

Shares