Carroll Ballard's "Duma," the story of (among other things) a friendship between a 12-year-old boy and an orphaned cheetah, could stand tall on the beauty of its images alone: Ballard and his cinematographer, Werner Maritz, show us vast green-gold South African plains, deep sapphire nighttime skies with the inky-matte texture of crepe and, most stunning of all, a cheetah moving so fast he appears ready to take flight. These are the sorts of images that draw us to the movies in the first place, and "Duma," in particular, demands to be seen on the big screen.

But unless Warner Bros. has a change of heart (or, more accurately, a change of business strategy), audiences won't get that chance. "Duma," and the sort of intelligent, visually rich filmmaking it represents, are endangered species.

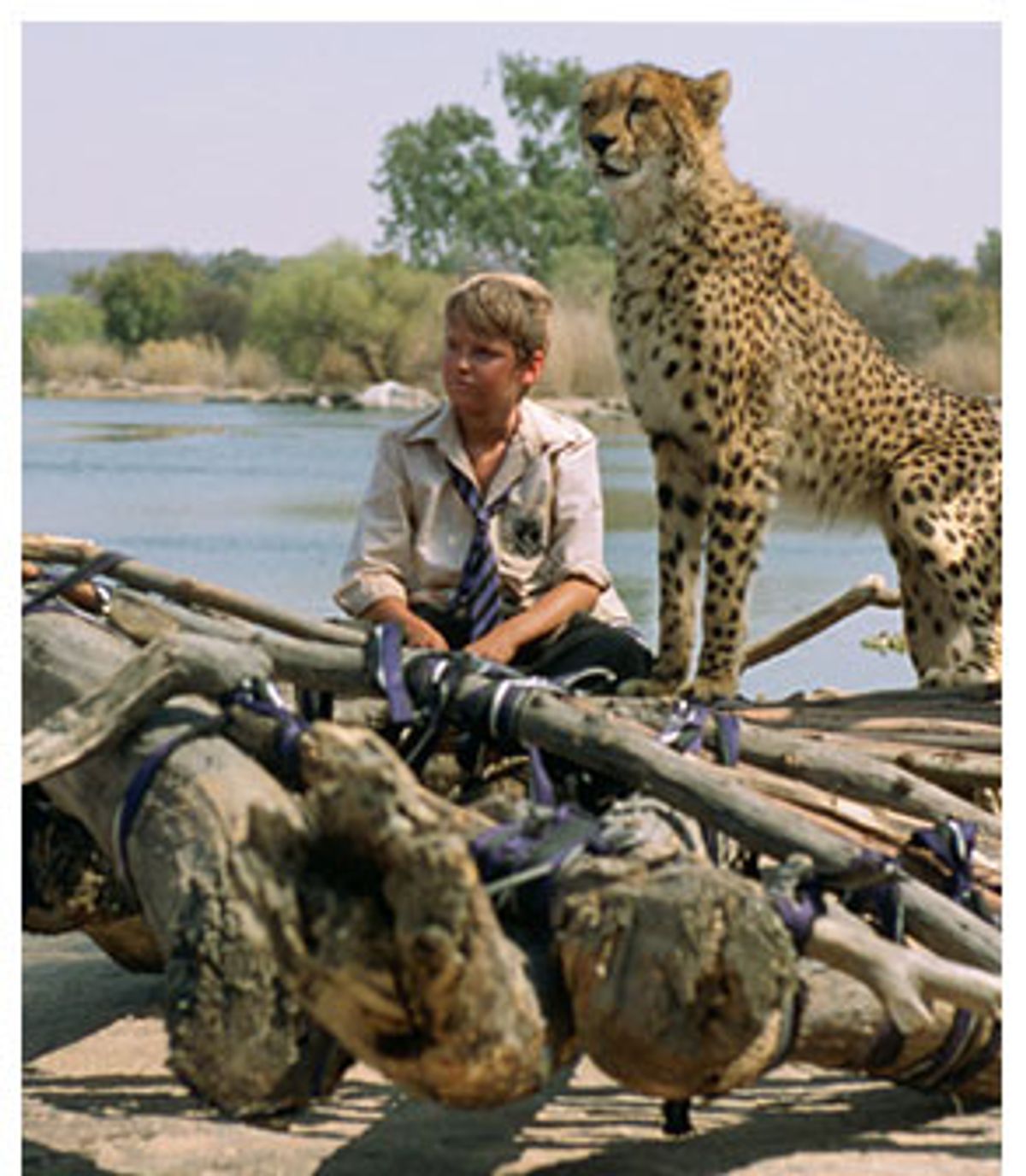

The story told in "Duma" is simple only on the surface: One night a young white South African boy named Xan (Alex Michaletos) is driving down a dark ribbon of road with his dad (Campbell Scott) when he spots an orphaned cheetah cub wobbling toward the danger of oncoming traffic. They scoop the cub into a net and look around for the mother, who's nowhere to be found. So they bring the cub home to their farm, and to Xan's mom (Hope Davis), where he quickly finds a place among the scrabbling chickens and lowing livestock; he spends his nights in purring luxury under the covers of Xan's bed.

But Xan's dad recognizes that as this big cat gets bigger -- he has been named Duma, the Swahili word for "cheetah" -- Xan will have to start thinking about returning him to the wild, where he belongs. "Duma's got to live the life he was born to," the dad explains. "His wildness is something he knows without even knowing it. It's in his bones, in his blood. Like a memory."

Those words are the beginning of a serious adventure for Xan and Duma, one involving loss and grief, but also one that proves to Xan he has the resources to deal with whatever comes his way -- they're in his bones, in his blood. "Duma" is the sort of story that's sometimes unthinkingly called formulaic, but the better word for it is "archetypal" -- it speaks to some of the deepest feelings, and fears, in all of us. (Karen Janszen and Mark St. Germain wrote the script, from a story by Janszen and Carol Flint; the story was adapted from a picture book by Carol Cawthra Hopcraft and Xan Hopcraft.)

Even so, it's what Ballard does with this story that makes it sing. Ballard's movies include the lovely "Fly Away Home," a picture about a girl's experience with a flock of baby geese that itself feels airborne, and "The Black Stallion," one of the most beautifully filmed adventure stories ever made (for kids or adults). He's the master of a rare kind of movie storytelling; there is no other filmmaker quite like him. Timeless without ever seeming old-fashioned or hokey, his movies feel like ballads that have been passed down from the generations before us, blends of words and images that constitute a kind of cross-cultural visual music.

And while Ballard's movies always have potent undercurrents, his ideas emerge so subtly that you never feel beaten down by them. Xan and Duma's adventure takes them -- together, but without parental supervision -- out into the South African wilderness, where they meet a drifter named Ripkuna (the wonderful Eamonn Walker). Ripkuna has left his village and his family; he set out to build a better life, but somehow (we're not told exactly how), he has failed. Ripkuna and Xan eye each other suspiciously at first, and it takes a long time for them to bridge their differences. (When Ripkuna hands Xan his water bottle, Xan wipes the mouth of it, warily and with great obviousness, before drinking.) The friendship between Xan and Ripkuna emerges slowly but deepens quickly. And Ripkuna, indifferent to Duma at first (at one point, early on, he eyes him as possible food, a notion Xan stomps out immediately), eventually realizes that this grand creature has something to teach him, too.

"Duma" is a movie about many things -- about loyalty, about the majesty and danger of nature, about self-sufficiency in the face of the uncertainty and, sometimes, the hardship of childhood. It's also about parenthood, and the things we pass on to our children even when we're not overtly "teaching" them (or maybe especially when we're not teaching them). This is also an adventure tale with lots of danger and suspense, made in a way that doesn't abuse children's emotions or underestimate their intelligence. (Needless to say, adults are likely to enjoy it just as much, if not more.) And it's put together so fluidly that it approaches perfection.

But before we start rejoicing that a movie like "Duma" can still get made, let's cut to the bad news: Its studio, Warner Bros., doesn't know what to do with it. And unless the company changes its mind, you're not likely to see "Duma" on the big screen, unless you happen to live near Chicago, where it opens this Friday for one week -- possibly longer if it does well.

"Duma" had a test run last spring in three markets, San Antonio, Phoenix and Sacramento, Calif. (It has also had a limited release in the U.K.) The picture had two showings in New York, at the Tribeca Film Festival last April, where I was lucky enough to see it. The cost of marketing a picture like "Duma" nationwide is about $25 million, and the studio, unsure of the movie's earning potential, isn't sure it wants to make that commitment. ("Duma" cost around $12 million to make.) But after Roger Ebert spoke favorably about the picture, Warner did agree to give it a Chicago release. How "Duma" does in that market will help determine its future.

And after seeing the success that Warner Independent Pictures has had with the documentary "March of the Penguins," which has been in the top 10 for several weeks and whose release has been gradually widened to build audience awareness, it's hard to understand why Warner Bros. can't do the same thing with "Duma" -- especially since the audiences for the two movies are likely the same. After I saw "Duma" at Tribeca last spring, a couple sitting next to me, who had come with their little boy, said they couldn't wait to see it again when it opened. When I told them that Warner Bros. was not planning to open it, their faces fell. This, they explained, was the type of movie they looked for to see with their kid. What, they asked me, was the studio thinking?

In an interview with Time Out Chicago this week, Ballard says that "Duma" may mark the end of directing for him; he no longer has the heart to do it. Ballard hasn't made a lot of movies, and although his pictures are often revered by critics and beloved by the moviegoers who get to see them, they're not the kind of blockbuster moneymakers that the studios are looking for, perhaps now more than ever. The harsh reality is that studios are -- often to the detriment of audiences -- in the business to make money.

But in the case of "Duma," Warner Bros. is missing gold by seeing only green. The movie features an astonishing shot of Duma, crouched with Xan and Ripkuna before the nighttime fire they've built to warm themselves. His posture is a comically awkward composition of paws and limbs -- somehow, cheetahs look most "right" when they're running, not sitting. But then the camera gives us a close-up of his face, alert but pensive, his eyes the size and shape of giant ancient coins. Duma, luminous and wide-eyed in the firelight, may not be the color of money. But he sure looks like gold to me.

Shares