Being a lover of the classics is such a humorless gig, particularly when it comes to movie adaptations of great books. Late last year, the Jane Austen Society, as well as many plain old Jane Austen fans, dipped Joe Wright's lively "Pride & Prejudice" into their home test kits and found its Austenticity lacking: The country dance was too noisy and undignified, the characters took unforgivable liberties with the book's dialogue, and too much of the story happened outdoors. The ending seen in American theaters, in which Lizzy and Darcy actually kiss, was the last straw; in Austen's world, characters never kissed, even, apparently, in private.

The terrible and beautiful thing about adaptations of great books is that they're always intruders, invading our already crowded imaginations and demanding a little space of their own. But their audaciousness is often mistaken for a kind of overwrite capability, a demonic code written expressly to erase (and not just accessorize) the joyful and intensely private experience of reading. How much power we cede to a movie adaptation of a beloved book is up to us, not it, and yet we can't help seeing a "failed" adaptation as the dangerous enemy of everything we hold dear.

As an adaptation of Laurence Sterne's 18th century comic novel "The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman," Michael Winterbottom's "Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story" is surely a failure, considering that less than a third of the movie even deals with scenes from the novel. But as an attempt to wrestle with the intricacies of adaptation -- and as a way of facing up, with good humor and humility, to the reality that no matter how much integrity you bring to the task, you're bound to mess up -- it may be the most honest kind of adaptation imaginable. "Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story" is, among other things, a movie-within-a-movie, a sly meditation on the haphazard, unpredictable nature of creativity, and an affectionate cuff on the nose for actors everywhere, exposing, in good fun, their vanity, insecurities and tendency toward jealousy. The movie's delights unfold like an intricate, exotic puzzle: Winterbottom has built a detailed, miniature universe inside a sugar egg.

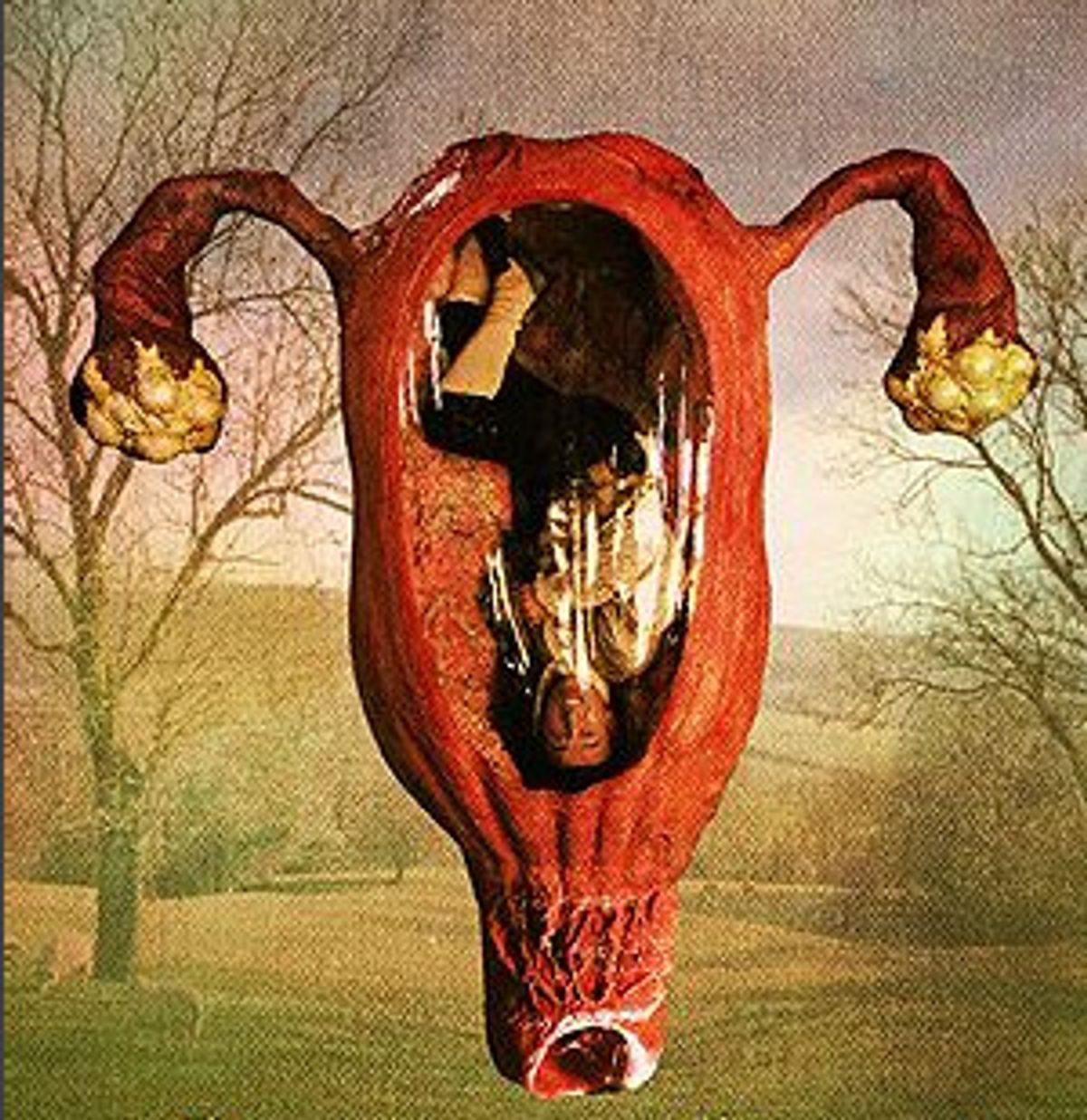

Sterne's novel is largely considered unfilmable, and by the time we see the actor who's playing the title character here (an actor named "Steve Coogan" --who's played by the actor Steve Coogan) hanging upside-down in an oversize facsimile of a womb -- complete with a realistically spongy-looking pinky-red interior -- we understand why. I confess, with a degree of shame, that I've never read "The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman," but if you haven't, either, we're not alone: One of the running gags of "A Cock and Bull Story" is that nearly no one on the set of the movie-within-a-movie has read it, either. (At one point, Coogan thumbs through a copy, desperately looking for a scene he's been told is crucial, grumbling, "Can you believe a book as thick as this doesn't have an index?") Sterne's novel is, as Coogan explains to a journalist in the movie, a groundbreaking work -- "a postmodern novel before there was any modernism to be 'post' about," he says, summing it up nicely. The book includes a whole page that's nothing but black space, as well as some intricate typography effects and illustrative squiggles. It's a story told in digressions and rambling asides, and that's exactly how Winterbottom has structured the movie, too. Although it may seem formless at first, there's really a ramshackle rigorousness to it.

Coogan plays interlocking roles: the hero, Tristram Shandy; the hero's father, the pompous, overeducated Walter Shandy; and a version of the "real" Steve Coogan who has just had a child with his longtime girlfriend, Jenny (the luminescent Scottish actress Kelly Macdonald). Jenny and the baby have come out from London to the country, where the movie is being filmed, just so this small, new family can spend an evening together. Coogan is happy enough to see her, but he's a little distracted: He's been flirting, in a somewhat innocent but potentially dangerous way, with Jennie (the sly, surefooted Naomie Harris, of "28 Days Later"), a young, vitally attractive woman who's working as a runner on the film. And he's engaged in an ongoing rivalry with another actor in the movie -- an actor named "Rob Brydon," who's played by real-life actor and comedian Rob Brydon. Brydon has been cast as Tristram's uncle, Toby, an eccentric figure who, during wartime, suffered a mysterious injury in a very private place -- "just beyond the asparagus," he explains to his love interest, the Widow Wadman (played by Gillian Anderson, in a small but perfectly shaped performance), as they stroll through the scale-model battlefield he's arduously built in the garden on the Shandy estate.

Coogan worries that Brydon's performance will overshadow his, even though he knows he's the star; he pesters the wardrobe woman for shoes with a thicker sole, so he'll appear more physically imposing than his colleague. ("It should be like I'm Gandalf and he's Frodo" is his directive.) The friction between Coogan and Brydon is the movie's chief driving force, and their conflict carries straight through the movie's credits and perhaps beyond, even after both this movie and its movie-within-a-movie have ended. They bicker and banter, needling one another with not-so-subtle jabs ("Jenny told me how it hasn't been as good after the baby"). Brydon -- who, early in the movie, delivers a marvelous soliloquy on the yellowness of his teeth -- has delusions of leading-manhood, which Coogan waves away dismissively. But whenever Brydon's back is turned, Coogan's self-doubt manifests itself in little furrows of worry across his forehead. Both Coogan and Brydon are by turns endearing and annoying, and part of what make these performances so fun is that we're not really sure how we feel about these characters from one moment to the next. We may laugh at the parade-float size of their egos, but deep down, we know just how they feel.

"A Cock and Bull Story" suggests how infuriating and obnoxious creative people can be, only to circle back and remind us, gently, how much we rely on them for entertainment and pleasure. Winterbottom pokes fun at his characters (and his actors), but his deep affection for them is always clear. (The screenplay, credited to some dude named Martin Hardy, was really written by Winterbottom's longtime collaborator Frank Cottrell Boyce. The dialogue feels bracingly improvisational, and much of it very well may be.)

Serious-minded, thoughtful moviegoers often claim they want their movies to be about ideas. But movies that are "about" ideas are often lonely places, empty, echoing churches that make you wonder, Where have all the people gone to? I think Winterbottom cares about both ideas and people, but his ideas speak through his characters, not over them. And even though "A Cock and Bull Story" has some thematic similarities to Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman's "Adaptation," it's a far more challenging, and far less self-conscious, piece of work -- in addition to being much, much funnier. Winterbottom, unlike Kaufman and Jonze, doesn't fetishize creativity; he lets it ride him like a Harley on a rough stretch of road, and if he emerges a little bruised and battered, at least he comes up laughing.

And Winterbottom, always in tune with his actors' capabilities, gives them plenty of room to roam between their lines of dialogue. He doesn't underestimate the value of slapstick (Coogan has a great bit in which he shows us what happens when a hot chestnut is dropped down one's pants), but he allows his actors their moments of tenderness, too, as when Coogan sings his distressed infant to sleep with a velvety baritone lullaby. His colleagues and Jenny, enjoying drinks in the common area of the inn where the cast and crew are staying, overhear him on the baby monitor and later tease him mercilessly, but the endearment we feel toward him can't be dissolved. "Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story" -- perhaps, like the book it's almost based on -- is a comedy embedded with secret tips for better, more enjoyable living. The best way to survive in the world is to take pleasure in its absurdity, and, of course, to maintain the ability to laugh at yourself. Extra points to you if you can do so while hanging upside-down in a giant womb.

Shares