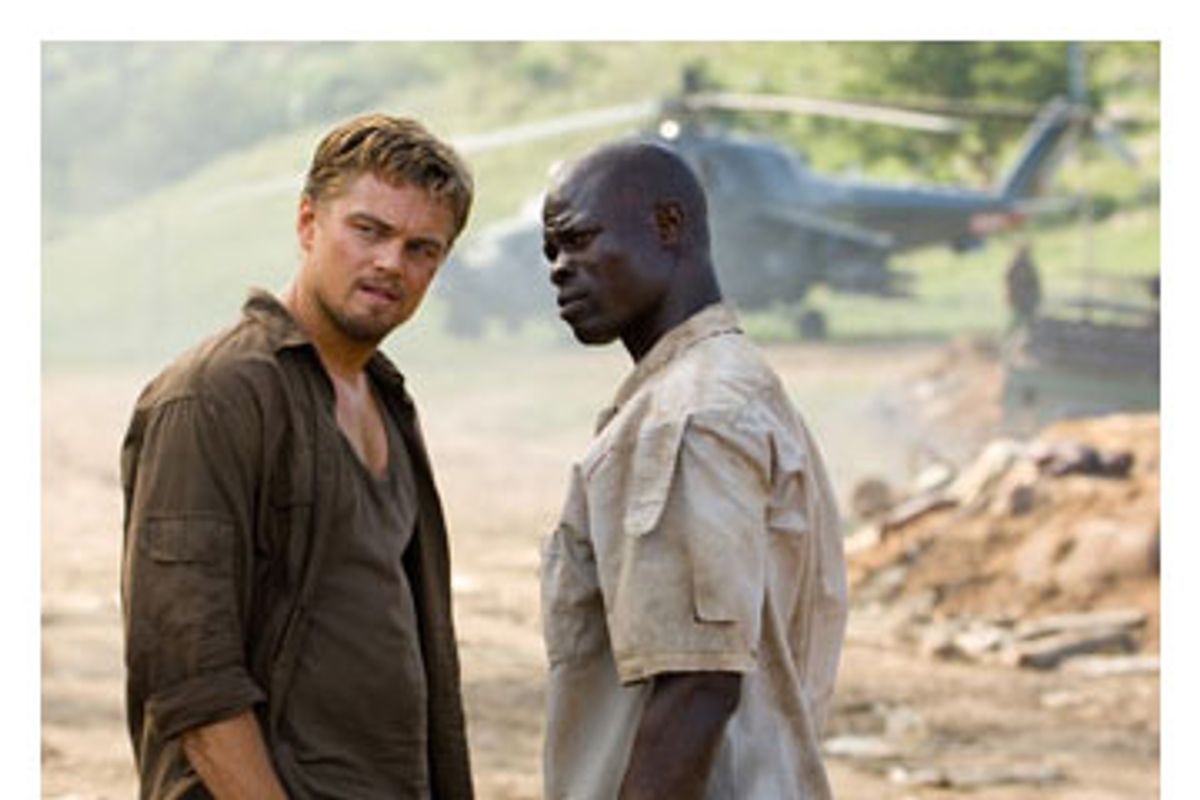

"Blood Diamond," set in late-1990s Sierra Leone, before the end of that country's civil war, is a public-service announcement masquerading as an adventure story, a picture made with a great deal of enthusiasm and conviction -- just not enough to make it any good. Leonardo DiCaprio plays South African smuggler and all-around wheeler-dealer Danny Archer; Djimon Hounsou is Solomon Vandy, a Sierra Leone fisherman whose family has been carried off by rebel fighters. (The rebel raid on Solomon's village, which occurs early in the picture, is a sharp snapshot of violence and terror that both sets the movie's somber tone and renders its later action scenes superfluous to the point of tastelessness.) Solomon, his family gone, is forced by his rebel captors to work in the diamond fields, where he discovers a giant pink gem that he risks his life to hide. Archer, who makes his living trading diamonds for arms, learns of the stone's existence and becomes driven to find it, but he needs Solomon's help to do so. Solomon, knowing the diamond is his only hope of getting his family back, reluctantly agrees to cooperate, and the two form an uneasy union as they troop through forests and grassland, courting death at the hands of machine-gun-happy rebels.

"Blood Diamond," which was directed by Edward Zwick (whose last picture was the numbingly noble "The Last Samurai") and written by Charles Leavitt (from a story by Leavitt and C. Gaby Mitchell), is a fictional concoction with recent history as its backdrop: From 1991 to 2002, Sierra Leone was riven by an internal conflict in which warring factions fought for control of the country's diamond resources. Diamonds were traded for arms; those stones, known as "conflict diamonds," eventually made their way into the marketplace, which meant that those who purchased them were, wittingly or otherwise, complicit in funding atrocities, some of which (including attacks on small villages, in which citizens, including women and children, were gunned down, the fearful survivors forced into refugee camps) are depicted here.

It's a story Zwick tells eagerly and enthusiastically -- just not very effectively. It is possible to build affecting, responsible dramas around horrific real-life events, as Terry George and Michael Winterbottom have with, respectively, "Hotel Rwanda" and "Welcome to Sarajevo." Both of those movies used storytelling (and carefully wrought performances) to open our eyes to real-world issues of human suffering; the difference between them and "Blood Diamond" is that, in Zwick's movie, the drama and even, to an extent, the depicted suffering feel like an afterthought. He toggles back and forth between exposing us to genuine horror (there are several deeply disturbing sequences of children being brainwashed and trained to use weapons) and providing the usual action-movie quota of explosions and gunfire (at the hands of bad white guys -- in other words, people we don't have to care about). That violence feels generic and rote. "Blood Diamond" is preachy infotainment that wants to offer thrills, too -- an uneasy hybrid.

On some vague level, it's certainly possible that "Blood Diamond" could "raise awareness" -- a term that always makes me think of a groundhog emerging, blinking lazily, from his hole, only to retreat knowing that he at least made the effort to see his own shadow -- about the importance of knowing where all of our consumer goods come from. The diamond industry has not been happy about "Blood Diamond," and launched a public-relations campaign last fall to assure consumers that conflict diamonds are no longer on the market (partly because of a 2003 agreement known as the Kimberly Process, which requires rigorous screening of all diamonds entering the marketplace).

But where does raising awareness end and browbeating begin? Zwick shows us a few shots of shallow-looking blond women cooing over giant stones as their fiancés look on, getting ready to open up their wallets. (The movie addresses hip-hop stars' penchant for bling far more obliquely, by giving us just the merest glimpse of a hip-hop video -- although it's important to note that in real life, a considerable number of hip-hop stars, including Kanye West and members of Wu-Tang Clan, have urged consumers to be aware of the origin of the diamonds they're purchasing.) On the one hand, no one with a conscience should buy a diamond unless he or she knows where it came from. On the other hand, should Zwick really be using a glorified action movie to scold us?

There's no doubt the actors here feel passionately about the material; it's too bad it isn't worthy of them. Jennifer Connelly plays a principled journalist (she's also, of course, DiCaprio's love interest) who listens intently as Solomon tells her about the violence in his country. He suggests to her that if she writes a story about the situation, Americans will read it and offer help. "Probably not," she says in clipped tones, a clear-eyed assessment that's one of the sharpest, smartest things in the movie.

DiCaprio and, especially, Hounsou are both terrific. There's still enough of the boyish squirt in DiCaprio to make him believable as a charming, if slimy, rapscallion. But Hounsou is the soul of the picture. Toward the end he has a speech that a lesser actor might have ground into sentimental mush. But Hounsou steers the moment steady and true, and the look in his eyes reminds us that the things few of us give a thought to from day to day -- home and family, security and food -- should never be taken for granted. Hounsou, single-handedly, does what the movie around him fails to do: He opens our eyes to the rest of the world.

Shares