Sometimes the resurfacing of a lost movie is more than just a chance to get acquainted with a forgotten gem of filmmaking. Sometimes it feels more like the discovery of a lost world, as if a celluloid Atlantis were rising before our eyes. That's the feeling you get watching Alberto Lattuada's buoyantly melancholy dark comedy "Mafioso," which was released in 1962 but has been rarely seen in the United States: It's now being rereleased by Rialto Pictures (whose role as excavators of the lost and forgotten seems more and more important in a world of too many throwaway contemporary movies), opening this week in New York and next in Los Angeles, with other cities to follow.

In the United States, Lattuada's name doesn't have the same currency as those of his compatriots Fellini, De Sica and Antonioni. In fact, he gave Fellini his first break as a filmmaker, sharing a directing credit with him on "Variety Lights" (1950). But "Mafioso" makes you want to see more of what Lattuada, who died in 2005, had to offer. Calling "Mafioso" a black comedy feels slightly incorrect: It's too subtle, its tone shifts too deft and prismatic, to be called anything so starkly definitive as "black" -- "charcoal" is more like it. And even though "Mafioso" is terrifically funny in places, it's likely to leave you feeling disquieted and unsettled. It's as if Lattuada had snuck in, while we were busy chuckling at both the broad jokes (involving female facial hair) and the sly ones (about the ridiculousness of macho posturing), and brushed the thing with a quiet glow of despair.

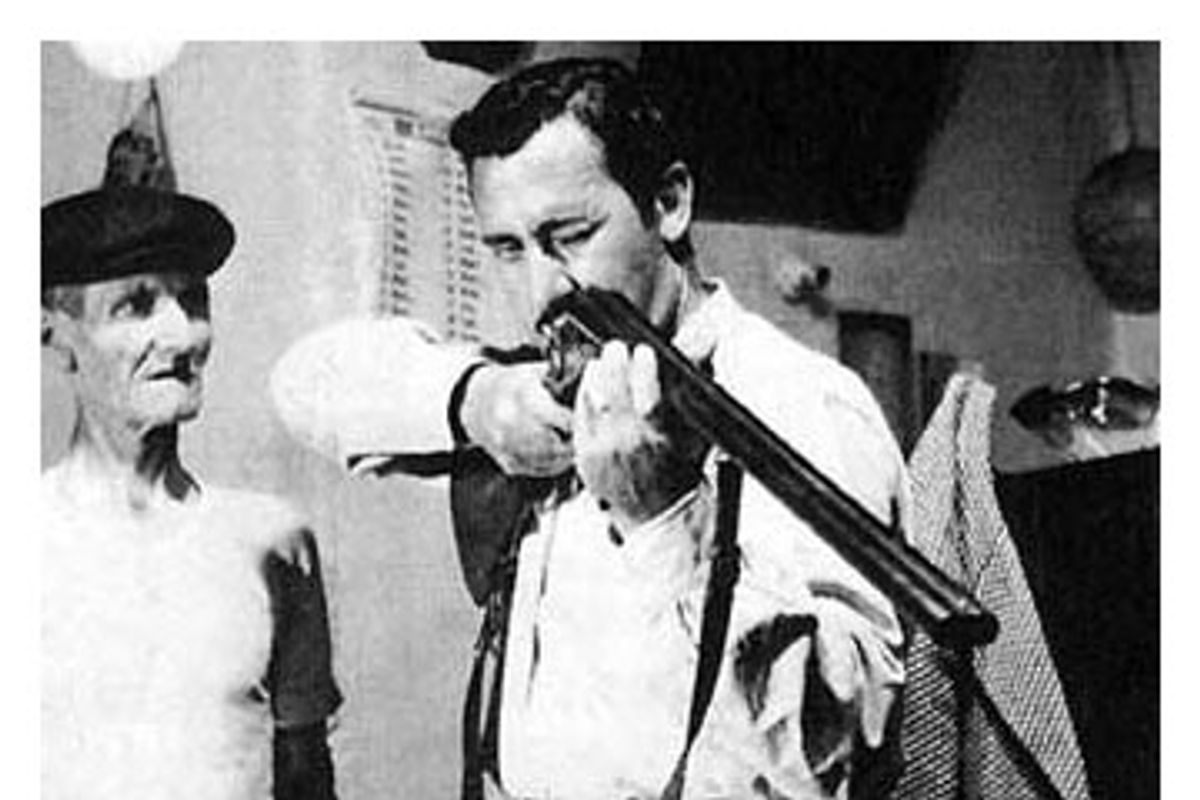

There's also, as the title implies, crime in "Mafioso." But to tell you too much about that would diminish some of the film's numerous pleasures. For now you just need to know that Alberto Sordi -- the much-loved comic actor who appeared in Fellini's "The White Sheik" and "I Vitelloni" -- plays Antonio, a successful auto-plant manager who's about to leave Milan for a two-week holiday with his wife, Marta (the pouty-sexy Norma Bengell), and their two adorable blond daughters. He's bringing his family back to his Sicilian hometown for the first time; he himself has not been there for years, and he can't wait to see his parents and his old friends, and to reacquaint himself with the glories -- power lines and all -- of the countryside.

There is, of course, a dark cloud hovering over Antonio's sentimentality for his home, and we catch glimpses of it early on: Just before he leaves on vacation, his boss, not a native Italian but an Italian from Trenton, N.J., praises Antonio's sturdy work ethic -- and then gives him a small package to deliver to Don Vicenzo (Ugo Attanasio), who reigns as godfather in Antonio's small hometown.

But not even Don Vicenzo, with that ominous paternalistic gleam in his eye, is as scary as Antonio's mother, a dour creature dressed in black who tearfully clings to her returning son while greeting her blond, urbane (but unfailingly kind and polite) daughter-in-law with a stony glare. The script here is by Marco Ferreri (who went on to become one of Italy's most provocative directors), Rafael Azcona, and the acclaimed screenwriting team Age Scarpelli (Agenore Incrocci and Furio Scarpelli, who also wrote Pietro Germi's marvelously swaggering comedy "Divorce Italian Style," as well as Sergio Leone's "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly"). The gags here manage to seem understated even when they're obvious: Finally arriving at the homestead (in a sequence that's beautifully, wickedly extended, shot in one long take), Antonio catches sight of his mustachioed sister's bouffant do for the first time in years. "Some new hair!" he exclaims without missing a beat, an improvised, dada compliment, although the way the poor girl blushes in response is even funnier.

Lattuada freely pokes fun at provinciality: One of the movie's great jokes revolves around the way the local men boast of their great success with women, even as they lounge around the local beach building a highly unrealistic nudie-cutie out of sand. But city folk aren't beyond reproach, either, and Lattuada and Sordi conspire to find ways of turning our own snobbery back on us. Sordi is wonderful here, and watching him, you immediately understand how much he must have meant to Italian audiences throughout the last half of the last century. (When he died, in 2003, some 60,000 fans lined up in Rome to pay their respects; one 19-year-old mourner, quoted on CNN, said, "I cannot bear to see him dead; it's as if my grandfather had died.")

Sordi is an elegant comic actor in the vein of America's William Powell; the world may confound him, but it can never rumple him. In an early scene, he steps into his boss's office, having removed the pristine white coat he wears on the shop floor to reveal a scrupulously tailored summer suit, complete with silk pocket square. I found myself transfixed first by his face -- an expressive, pliant, not-quite-handsome face, whose eyes have the mischievous promise of question marks -- and then by the fine hand-stitching on the lapel of his jacket. I caught myself, ashamed: I should be looking at this wonderful actor's face, and not at the stitching on his jacket. But then I realized that for Sordi, the stitching is part of the seduction. The way he wears those lapels is key to his command of the screen. His Antonio is a fine man, a proud man, worthy of respect: Sordi might think that if you haven't noticed the stitching on the jacket, he hasn't done his job.

Sordi's greatness -- his easy physical grace -- is particularly resplendent in a scene that takes place in his family's compact but nicely furnished city apartment, just as they're getting ready to leave for their holiday. The place is a bit chaotic, as Marta and the girls scramble to gather their things, but Antonio is untouched by their disorder. He strides into the bathroom -- all the while speaking authoritatively to his wife, detailing the family's travel plans with the assuredness of a born auto-plant foreman -- and picks up an electric shaver, buzzing it around the contours of his face. With the other hand, he takes up an electric shoe polisher (he hasn't stopped talking for even a fraction of a second) and proceeds to buff his understated-yet-perfect oxfords to a high shine. This is multitasking at its finest, efficiency as comic symphony.

But in "Mafioso," modernity clashes with the old ways: The urban world saunters into the provincial one, hoping to shove it aside with the bravado of its shoulder pads. And yet nothing, as Sordi's performance and Lattuada's film tell us, is that simple. The miracle of science can smooth your whiskers away and make your shoes gleam. But it can't make you forget where you come from.

Shares