What's really surprising about Sarah Polley's directing debut, "Away From Her," is not that a 28-year-old actress made a film about older people confronting Alzheimer's disease. It's true that not many young people, or old people either, want to think about this subject, but anybody who's seen Polley tackle wrenching topics in her acting roles certainly won't be shocked. She's played a woman dying of cancer ("My Life Without Me"), a survivor of Balkan-war atrocities ("The Secret Life of Words"), a woman who forges a friendship with a mythical Icelandic monster ("No Such Thing") and, oh yeah, a woman trapped in a shopping mall by flesh-eating zombies ("Dawn of the Dead").

No, what's startling about "Away From Her," which Polley adapted herself from Alice Munro's short story "The Bear Went Over the Mountain," is how clear and precise and composed it is. This isn't a neophyte's film; it's a film made by somebody with an innate understanding of cinematic language and a striking personal vision. As Polley said when I interviewed her in New York recently, every frame of the film is suffused with brilliant winter sunlight, and that cold light is illuminating unexpected corners of the 40-year marriage between Fiona (Julie Christie) and Grant (Gordon Pinsent). A wry, dry, elegant woman, proud and vain and intelligent, Fiona can feel her mind and her memory slipping away. She doesn't want to inflict her disease on Gordon, but her decision to move into a nursing home becomes an unexpected new beginning for both of them.

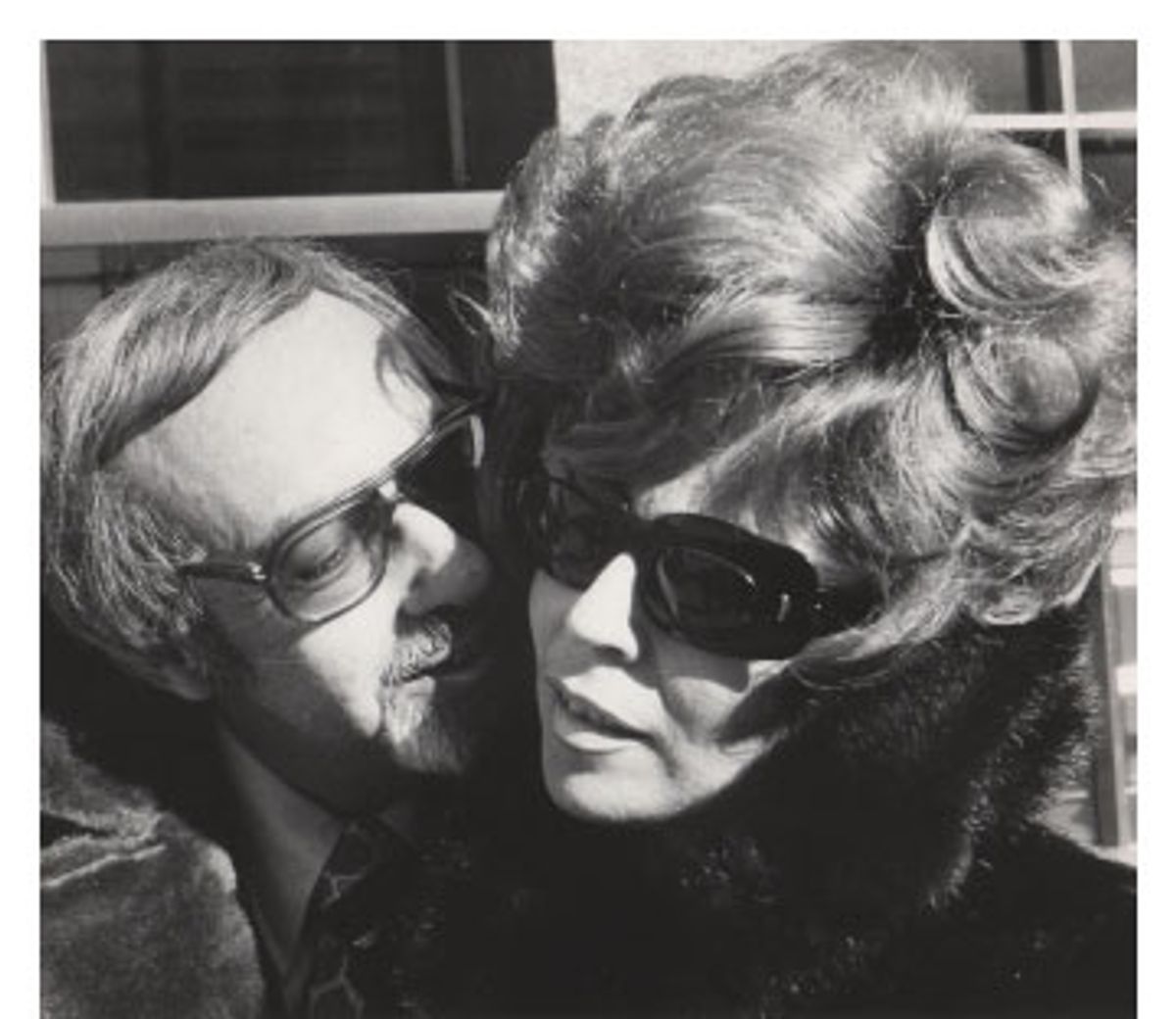

Inevitably, Christie is the focus of the film, both visually and thematically. She's nearly as beautiful as she was 40 years ago in "Doctor Zhivago" or "Far From the Madding Crowd," but the effect is totally different. Her hair has gone white and as Fiona she dresses largely in white clothing, sailing across the white snow and white light of Polley's Ontario backdrop like the carved figurehead of a great ship. At first, Fiona and Grant seem like a tender, affectionate couple, both still physically vigorous but facing the difficult closing chapter of a loving life together.

To listen to a podcast of the interview, click here.

To subscribe: Click here to add Conversations to iTunes or cut and paste the URL into your podcasting software:

As anybody who knows Munro's work will suspect, the path of this narrative is twistier and thornier than that. All the unresolved issues below the surface of Fiona and Grant's marriage don't disappear just because Fiona is ill; if anything they resurface with a vengeance. Of course Fiona can't ultimately control the progress of her disease, but she's fully able to exploit the strange new opportunities it offers her. For all its gentle Canadian luminosity, "Away From Her" becomes much funnier, and much darker, than you expect. As Polley puts it, this film recognizes that people near the end of their lives are still adults, not angels or kindergartners; they're just as capable of betraying each other and keeping secrets, just as driven by sexual desire or jealousy, as the rest of us.

In person, Polley herself is a pretty, unaffected woman who looks younger than 28 and speaks (unlike most of her movie characters) with a pronounced Toronto accent. She could definitely still play sorority-girl roles if she cared to. She's friendly and laughs easily, but she also emanates drive and direction. Most movie directors ramble on and on in interviews, pursuing their own thoughts through lengthy discussions of influence and theory and technique. Polley's been reading lines for a living since she was 6 years old; she answers a question crisply and stops, waiting politely for you to ask the next one. Only when we began discussing the possible nursing homes of the future did I feel her go off-message and improvise a little. (Click here to listen to a podcast of the interview.)

Polley fully intends to keep acting as she pursues other directing projects; she'll appear in HBO's forthcoming miniseries "John Adams" and will star opposite Jared Leto in a new film from Belgian director Jaco van Dormael. Much as I'd hate to lose her intense, unsettling screen presence, "Away From Her" is something special. If it ever becomes a choice between Polley the actor and Polley the filmmaker, I'd tell the zombies to wait.

When this film premiered at Sundance, it got a lot of attention just for the subject matter, even before people had seen it. I guess we don't believe that a film about older people, about Alzheimer's disease, is going to be box-office magic.

Wouldn't it be interesting, though, if it was? If it outdid "Spider-Man" by like $100 million? It would be the upset of the year.

Is that your prediction?

That is definitely not my prediction.

Talk about the Alice Munro story, and how you decided to make it into a film.

I read the story when it first came out, five or six years ago. It was originally called "The Bear Came Over the Mountain." I thought it was the most interesting portrait of a marriage, of memory and guilt, that I'd ever seen. First and foremost, I thought it was a love story. Maybe because I was at the beginning of a relationship, it was really interesting to me to look at what a marriage looks like after 44 years, what you do with everything you've done with each other, and to each other.

Well, and it's not a sentimental portrait of old age, or a long marriage. We're not talking about "On Golden Pond" here.

We're not. In a strange way, we really do people a disservice when we show anybody over 45 or 50 as somehow having lost all sense of their sexuality, as if they suddenly have no darkness and no edges and no sexuality. I thought what was so amazing about the story was the portrait of these two incredibly vibrant people with a lot of chemistry and a lot of undealt-with threads, a lot of things that have become tangled up.

I don't know how much you want to explain what happens. Julie Christie's character decides to go into this facility, and surprising things happen.

I'm comfortable saying that she falls in love with another man in the retirement home, and her husband is forced to witness this abandonment and betrayal of him, in the same way that she was forced to live through that in their younger years, when he was sleeping with younger women.

Talk about the look of the film, the visual sensibility. It's very distinctive.

For me the overriding visual palette that we were working with was the idea of this very strong, sometimes blinding winter sunlight that should infuse every frame. I didn't want the visual style to draw too much focus to itself. I felt like this needed to be an elegant and simple film, and that it had to have a certain grace.

Did you learn anything specific from the directors you've worked with that helped you make this film?

You absorb a lot from people you work with. Certainly people like Atom Egoyan or Wim Wenders, people whom I've really looked up to, have greatly informed the way I approached this film. At the same time, what I've learned from being an actor is that every director has to reinvent the wheel a bit, invent their own process and make that a reflection of who they are and how they communicate. So I was also very conscious of the idea that I had to figure out who I was as a filmmaker, and not be too imitative.

A Canadian friend of mine asked me if "Away From Her" seemed like a Canadian film. My answer was yes, but I wasn't really sure what I meant. What's your answer to that?

Yeah, I think it is a very Canadian film, and very identifiable as such. I don't think I went out of my way to make a statement about that, but I think that in Canada we're so used to hiding the fact that our films are Canadian that simply not hiding it seems like a political statement. But yes, absolutely. It very much has that sense of place in it.

David Cronenberg once told me that he thinks part of the reason his films seem strange to Americans is the Canadian setting. It seems very familiar to us, yet subtly different.

That's really interesting. But you know what -- his films are pretty strange anyway. Let's face it! I mean, come on! People don't turn into flies just because they're Canadian.

For a long time, when people talked about important Canadian directors, there was him and Atom Egoyan. This is such an impressive film, I don't know -- are you ready to be the third one on the list?

I'm not sure about that. I'm not quite in that realm yet. Let's see how I'm doing in 10 years or so.

Certainly casting Julie Christie in your first film was a way of getting noticed. She doesn't act much these days, and has said that the part of her that used to be a movie star seems like a different person. How did you convince her to take the role?

I had worked with her as an actor [in "No Such Thing" and "The Secret Life of Words"] and she was a good friend by the time I had finished this script. And I did write it for her; I immediately saw her face in my mind when I read this character. But I also knew that I would get a few nos before I got a yes. She's a reluctant actor. It was a long process; it took about six or eight months. We had a lot of phone calls and meetings and e-mails. Thank God she agreed to do it, because she was a huge factor in my wanting to make it in the first place.

Was it hard for you to say to Julie Christie, "Listen, that take wasn't right. We've got to do it again?"

She was so into the process of making the film, and was so supportive of me, that I didn't feel daunted by the idea of directing her. I mean, I did at first, but she was so welcoming.

How easy or difficult was it to get this made? You are obviously well known in the business, but it was a first film, your own script and not the sexiest subject matter in the world.

Well, this was all funded by Telefilm Canada, so it was all public money. Which is a great way to make a first film, because you have creative control. Actually, I thought this would be hard to get people behind, but so many people are dealing with aging parents or grandparents, or Alzheimer's disease, or something in the realm of this story. There were a lot of people who felt a certain urgency to get it made. It was a lot easier than I thought it would be.

In the film, Julie Christie's character is actually pretty young for Alzheimer's, right? She's certainly vigorous.

Right. She's in her early 60s. That was important; that was part of what I wanted to convey in the film. Nobody thinks their parents are old enough, or their spouse is old enough, for this disease. When people we love succumb to this disease it is always unimaginable, because they seem young and full of life. That was important to me with Julie and Gordon. I cast these people where it would seem almost inconceivable that they'd be going through this.

My wife's grandmother is in a nursing facility not unlike the one in the film. I mean, so many of us go through this. And I have to say, you completely nailed it. The completely friendly, professional surface of life in those places, and the slightly sinister or creepy undercurrents below that. It was almost tough to sit through, it felt so real.

I spent tons of time in a retirement home with my grandmother. So this was personal to me, to some degree. I knew that environment and I wanted to capture it. I started working on this while I was visiting my grandmother, so I just became a sponge for everything that was going on, all the strange dynamics of the place.

Ultimately, it's like we haven't figured this stuff out yet, as a society. We can't go around saying, "These places are terrible. People shouldn't go into them." That's not realistic. There has to be a place for people who are suffering from these kinds of illnesses. Women, by and large, no longer stay home full time, so there's no longer someone to take full responsibility for their well-being. These places are necessary, and I don't think they're terrible. There are really great people that work in these facilities. They do sometimes veer into the realm of condescension, of being a kindergarten and not a place for full-grown adults. There are things I find incredible about them, and there are also other moments that are truly offensive. There can be a very institutional, administrative feeling to the way these people's lives are managed.

You have this character, the director of the facility, who's just perfect. She's brisk, professional, nice enough in her way. But she's basically a bureaucrat, pushing paper and moving the product.

Yeah, and in fact, I don't think she's a bad person. I just think she's dealing with hundreds of people every day, and with a lot of serious concerns. You can't stay emotionally engaged with all of them. You do get these people who've been to too many corporate retreats or something. I remember one tour of a retirement facility I once went to, when I was looking for a place for my grandmother. I was asking about the age range, because my grandmother was in her 90s at the time. So I asked, "Most of the people here seem to be in their 70s. Do you have any older people living here?" And the answer was: "Oh, we've got a few people in their 80s and quite a few in their 90s. We've got quite a crop." So I thought -- hmm, interesting way to refer to people older than you. A crop! There's a certain language that comes with this territory that's pretty off-putting.

I've started wondering about what those facilities will be like when we reach that age.

Oh, I've been thinking about that too. You know what I always thought about? When I would visit my grandmother we'd sit there and eat the Salisbury steak, the mashed potatoes and the green beans. And I'd think, oh my God, we are going to be such a difficult generation. By the time we get there, we're going to be like, "Where's the sushi? Where's the Indian food? Where's the organic stuff?" It's not going to be so easy to accommodate us.

Right. What night is pad Thai night? They're going to have to have high-speed Internet, or however that will work in 30 or 40 years.

They'd better.

Are they going to have cover bands that come in and do "London Calling" or whatever?

[Laughter.] It would also be interesting if those places stayed the same, if they stayed totally static, no matter what. So we all wound up eating Salisbury steak and listening to Frank Sinatra, and they just wouldn't adjust.

"Away From Her" opens May 4 in New York, Los Angeles and other major cities, with a wider release to follow.

More from Tribeca: Jia Zhangke's breathtaking "Still Life"; a serial killer in Beirut; a tender look back at '80s England (and its racist skinheads)

Most of the attention devoted to the Tribeca Film Festival, mine included, tends to focus on its air of Manhattanite insiderism and its array of quasi-glitzy premieres. This makes for lots of celeb sightings and moderately juicy copy, but also for evenings spent sitting through some profoundly mediocre motion pictures. But Tribeca also programs a passel of outstanding foreign films from all over the globe, and for some of them it'll be the one and only chance for paying American customers to see them on the big screen. I mean, I certainly hope that "The Optimists," the newest film from the great Serbian director Goran Paskaljevic, finds American distribution. But I'm not planning to go on a hunger strike while we're waiting.

I haven't seen "The Optimists" yet, or "Two in One," the film-within-a-film by the supremely mean Russian filmmaker Kira Muratova, or "Born and Bred" by Pablo Trapero, one of the hottest young Argentine directors. They're on my list as Tribeca winds down, and God knows if or when they'll ever be seen again after that (yes, even on Netflix or GreenCine). With the market for non-European films as weak as it is right now, I can't even be sure we'll get to see "Still Life," the stark and beautiful new drama from China's Jia Zhangke, one of the world's most celebrated directors. (It premiered at Tribeca on Wednesday night.)

Jia has always been interested in the dislocation of contemporary Chinese existence (his last film was "The World," set at a theme park outside Beijing), but as his movies have gradually broadened in scope they've also developed a current of wry comedy and even tenderness. "Still Life" is set in the extraordinary landscape around Fengjie, a small city on the Yangtze River that's being demolished and moved to make way for the rising waters of the Three Gorges dam, the largest such project in the world. In this end-of-the-world setting, life goes on after its fashion; in two parallel narratives Jia follows a working-class man and middle-class woman who have come to Fengjie to find their respective missing spouses.

One critic friend of mine has suggested that "Still Life" is a comedy of sorts, and he may be right. The missing husband and wife are found, after much effort, but their presence doesn't really resolve anything. Instead, the story moves forward as a series of remarkable images and tiny human encounters, almost meaningless in themselves. A man and woman dance on a riverfront promenade that will soon be submerged; another man does bad impressions of Chow Yun-Fat movie dialogue. In between workdays spent destroying their own city, demolition crews drink, stage fights with each other, wax rhapsodic about the beautiful Chinese scenery (as seen on banknotes).

It would be too easy to describe Jia's tone as ironic; it can be wistful or whimsical or deliberately obscure (I'm not sure what the spaceships are doing in this otherwise naturalistic film, frankly). One thing I'm confident about is that one viewing is not enough to absorb "Still Life." It strikes me as Jia's finest film yet, both a docudrama with obvious social and historical relevance and a subtle, slow, quietly powerful chronicle of human loss. It never seems inaccessible or willfully arty, but it won't yield all its secrets on the first date.

My favorite film of the whole festival so far, Ghassan Salhab's "The Last Man," is also composed of a myriad of small and enigmatic moments, but undoubtedly would strike some viewers as unbearably pretentious. If I tell you it's a serial-killer movie set in Beirut, that's accurate but conveys entirely the wrong impression. It's not a thriller but rather a slow, intimate psychological-nightmare film, both allegorical and symbolic.

Khalil, an upper-middle-class Lebanese doctor (played by the great Arab actor Carlos Chahine), feels some strange, unexplained connection to the serial murders; in fact his personality seems to be melting down. He has blackouts, seizures, spells of temporary deafness. He sees troubling things while scuba diving in the brilliant blue sea. His lovely city seems to be inhabited by ghosts and shadows, and Khalil himself may be among them. It's definitely not coincidental that Beirut is being bombed daily by Israeli planes and boats (during the recent war between Israel and Hezbollah), and life in the elegant Mediterranean metropolis feels once again on the brink of chaos.

If you have the patience to feel completely haunted and bewildered -- but haunted and bewildered in the hands of a master filmmaker, albeit one almost unknown in the West -- then "The Last Man" is an exhilarating cinematic experience. Much cozier, but nearly as potent a portrait of a society in decay, is Shane Meadows' "This Is England," an intimate memory film about a lonely, undersized boy who finds a home amid an ominous group of skinheads in the grimy, underemployed north of England, circa 1983.

Meadows ("Once Upon a Time in the Midlands") is a self-taught filmmaker in the working-class mode that produced Mike Leigh and Ken Loach, but with his own late-Thatcher worldview and an intimate, insider's understanding of post-punk British culture. Even the scariest, most thuggish of these skins, the racist ex-convict named Combo (marvelously played by Stephen Graham), is not a caricature. He's a wounded man on the edge of middle age who feels abandoned by his country and his family, with a tender side he opens only to 12-year-old Shaun (Thomas Turgoose). Combo's surrogate-dad love for Shaun is genuine, even if his expressions of it -- like joint outings to terrorize Pakistani shopkeepers -- leave something to be desired.

Shares