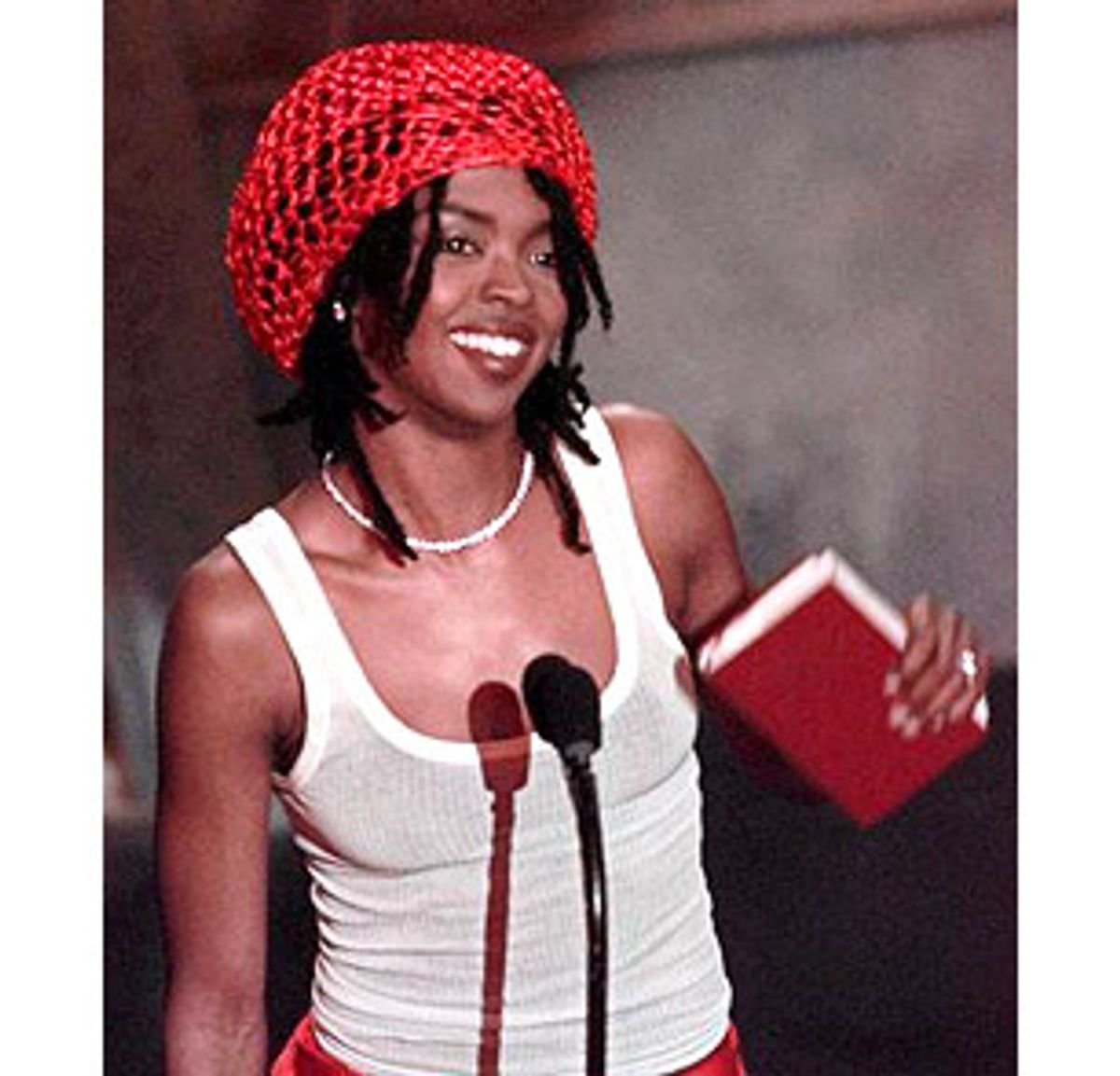

Hip-hop songstress Lauryn Hill was supposed to face the music today. Or, at the very least, face the musicians. Four beatmaker-songwriters who helped make the quintuple-platinum "The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" filed a federal suit against Hill in November 1998. They charge that she "used their songs and production skills but failed to properly credit them for the work." After months and months of delay, Hill won one final extension from U.S. Magistrate Ronald J. Hedges last week. But on June 21, she will be deposed as part of the discovery phase of their lawsuit.

She will be asked, under oath, a simple question: Who wrote those songs? But just beneath that question is a far more elusive one: What is a pop song, anyway?

The four plaintiffs -- Vada Nobles, Johari Newton, Tejumold Newton and Rasheem Pugh, who make up New-Ark Entertainment -- are credited on the record as performers, producers or contributors of "additional music or lyrics." Their suit maintains that they should have received credit as songwriters and producers, a contention denied by Hill, who says she wrote and produced the entire record. Do they have a point? Well, the answer depends on what their contributions were. But it also depends on what you think a pop song is. As rock and its offspring over the last 40 years have become steadily more dependent on technology and have moved away from clear melodies and simple moon-spoon-June lyrics, the question of authorship has often become muddled; now, amid the ongoing commercial domination of sample-heavy genres like hip-hop and electronica, the questions of what constitutes a song, and who deserves credit for songwriting, have never been more complicated.

Most artists make a distinction between the composition of a song and the recording -- the interpretation of that composition. Hit records can generate gobs of cash for recording artists. In the long term, however, even more money can be made by songwriters who -- with but one or two hit songs -- can enjoy years and years of steady royalties from record sales, radio airplay, video airplay and concert performance. For a songwriter, having your name on a hit song means you'll get more work, which leads to more royalties. No wonder, then, that everyone wants a slice of the songwriting pie.

But what are the pie's ingredients? In an age of sampled hooks and all-night studio writing sessions, the line between song and recording is almost hopelessly blurred. There's a lot of money riding on that blurry line, although money's not the only thing at stake here. One can never underestimate the lure of fame and respect. In our celebrity-obsessed and lawsuit-prone culture, musicians have become more assertive about demanding their share of it. And many recording artists resist sharing. It didn't come as much surprise when Hill's spokesman, Dan Klores, maintained that the New-Ark musicians were "appropriately credited for their contribution on the album," and chalked up their lawsuit as "an attempt to take advantage of her success."

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Before the explosion of rock 'n' roll, pop songs were largely written by professional tunesmiths. An almost-corporate division of labor was in effect: one that clearly separated the jobs of writers, arrangers, producers, session musicians and singers. Everyone had a job and every job was defined. But the rock era -- in the personas of Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly and then, more spectacularly, the Beatles and Bob Dylan -- invented the cult of the singer-songwriter. By the 1970s, with few exceptions, it was expected that a rock singer wrote his or her own songs, albeit sometimes with help from bandmates or producers. Pop music has come a long way from the days when professional writers sweated over banged-up pianos in cramped cubicles before running down to the studio with sheet music in hand.

Still, it was always clear who wrote what -- Mick Jagger (for the most part) wrote words; Keith Richards, the guitar parts. But as rock's genres have balkanized and recombined, all with complex admixtures of various species of technology, all of this has blurred. The traditional definition of a song -- a lyric set to melody over chord changes -- works fine for Jewel, Bob Dylan or Celine Dion. But it doesn't work for Metallica, Public Enemy, the Wu-Tang Clan or any other groups that build songs from riffs, beats and sound effects. Today's songs are fluid enough to embrace elements besides lyric and vocal melody. When a defining hook in a hip-hop song is its catchy bass line, or a metal song's hook is its snarling guitar riff, songwriting credit ought to be spread around. Right?

Well, sort of. The liner notes to "The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" read, "Produced, Written, Arranged and Performed by Lauryn Hill," before noting a few exceptions. For example, on "Lost Ones," a vehement song about betrayal, Vada Nobles is credited with "drum programming" and "additional production." "Lost Ones" is essentially a hip-hop song; it succeeds brilliantly on a tight beat, Hill's energetic rapping and her magnificent chorus. Nobles programmed the idiosyncratic beat that drives the song. If he came up with it, doesn't he deserve a share of songwriting credit? Is a beat part of the song? How about a bass line? Or a guitar riff?

What is a song anyway? Take "I'll Be Missing You," a smash hit for Sean "Puffy" Combs in 1997. Built on a sample from the Police's 1983 hit "Every Breath You Take," Combs credited the song to Sting, who wrote the Police tune, and the two lyricists who wrote the new words. For Police guitarist Andy Summers, this constituted a double whammy. "My job in the Police was to provide the guitar part, but I provided a rather seminal one there, which kind of made the song," says Summers, who received no writing credit, and never thought to ask for it.

Summers remembers the first time he heard his catchy little guitar riff as part of "I'll Be Missing You" on his son's radio. "My kid called me into his bedroom one night, and said, 'Look, Daddy, these people are ripping you off.'" After making a few phone calls, Summers learned that he had received some compensation for the riff -- Combs' Bad Boy Records had paid for the actual sample of the Police's album track, which Summers had, of course, performed on. However, since he never got writing credit for "Every Breath You Take," he also got no writing credit for "I'll Be Missing You." Both songs rely heavily on his riff, as Summers points out with typically English understatement: "I wonder what that song would've been like without it?"

If you go to any high school in America, play about two seconds of Summers' riff and ask the kids what song it is, they'll say "I'll Be Missing You." At this point, the song is commercially over, yet the guitar riff is essentially timeless. And at this point, it belongs to Sting.

The idea that a familiar and beloved guitar riff isn't really part of the song it made famous sounds crazy to anyone under 30. After all, when Beavis and Butt-head hurl their fists in the air and sing their old favorites, they don't shout the lyrics -- they scream the riffs. That's because a riff is an essential element of a song. Right?

Wrong, says Al Kooper, an accomplished session man, record producer and songwriter who has been on all sides of this issue. Kooper played organ on Bob Dylan's "Highway 61 Revisited" -- most memorably on "Like a Rolling Stone" -- among other records, and he believes passionately in the traditional distinction between the song and the arrangement. "If I can sit down and play the chords and sing the lyrics and melody, that's my song," says Kooper, 55. "Anything else is arrangement. That's why those words were coined."

Kooper is right, in theory; Sting might argue that all Summers was really doing was playing his chords in an interesting way. But even back in the '60s, songwriting credit wasn't doled out according to pure creativity. Many artist managers, who never wrote a note of music in their lives, stole songwriting credit by putting their names down on authorship forms. In this injustice lies a precedent for an expanded notion of songwriting. Another example of this is when white artists -- most notably Led Zeppelin and Eric Clapton -- appropriated old blues songs, changed a few lines and pronounced the songs their own.

In the case of Dylan's "Like a Rolling Stone," the song was written before Kooper ever got to the studio. Producer Daniel Lanois, who's worked with Dylan, Emmylou Harris and U2, notes, "Bob wrote the song. Bob can play it on guitar, he can play it on piano, he can play it any tempo he wants and any time signature he wants. The people in the studio are part of the construction crew invited to build the record, but not necessarily the song." Thus, Kooper's distinctive organ trill, an important element of the record, doesn't entitle him to a writing credit. "I wrote the organ part," he says, "but I would never go to Bob Dylan and say, 'I should get a piece of this.' I wrote the organ part. That's my job."

By this way of thinking, no session musician who comes up with a bass line, drumbeat or guitar riff is entitled to songwriting credit for simply doing his job, no matter how much those parts may define the record or song itself. To determine who deserves songwriting credit, Kooper suggests distilling a song down to its very essence, and ignoring the music on the record. "You can bang on a table and recite a rap lyric, and that's your rap song. Stripped down, that's the song."

The problem with distilling a song to its essence is that it's such slippery business. Kooper distills Public Enemy's "Welcome to the Terrordome" and comes up with Chuck D's lyrics and "banging on a table." To other ears, the thunderous squawks provided by Hank Shocklee and Eric Sadler -- two members of the group's Bomb Squad production team -- are as important to the song as the lyrics. Kooper has tradition on his side, but Public Enemy's Chuck D credited Shocklee and Sadler on "Terrordome" and most of the group's seminal songs.

Producer Jermaine Dupri, who at 27 is as accomplished in hip-hop as Kooper at 27 was in rock 'n' roll, also sees it differently from Kooper. A bass line does deserve a songwriting credit, he says, "if it's a very big part of the record. Five percent don't matter, but if you use it all through the record, it becomes a general part of the song."

Hip-hop songs, like many rock songs over the last 35 years, are often written on the spot in the studio. "If you asked somebody to come work, and you step out of the studio and they start playing something on their own, you might come back and say, 'Yeah, I like that. Let's use it.' Then you gotta give them credit." Dupri notes that drum programmers on hip-hop songs generally receive production rather than songwriting credit. This way, they get a share of royalties for their work without getting authorship of the song.

Another reason for sharing in hip-hop may be African-American cultural norms. "There's this Western European idea of one guy who sits down and comes up with the important thing -- the melody and the words," notes guitarist Peter Buck of R.E.M. "Whereas the African conception is that everyone plays together. Bo Diddley should be a millionaire for the Bo Diddley beat, but that isn't the way it works."

That is the way it works inside R.E.M. "We've always gone for a four-way split," says Buck. "The way I look at it, you're getting songwriting credit for riding around in the van for five years, not having a house or a girlfriend or any money. We go so far as to cut in people who aren't in the band, like [attorney] Bertis Downes. He's getting paid for all those years he did legal work for free, including getting us our own publishing company before we even had a record deal." According to this mind-set, a song is the product of the band almost as a family, and that family shares credit for the song. Well-paid session musicians who aren't long-standing members of the family, however, do not get a share.

One thing that Lanois, Dupri and Kooper all agree on is that session musicians who feel their contributions merit songwriting credit should open their mouths sometime before the record goes platinum, or else they come off as gold diggers. That's certainly how Lauryn Hill's camp regard the New-Ark plaintiffs. Another is that an artist or producer can avoid being sued by simply telling session musicians what to play. What's difficult to find agreement on is the definition of the song itself. Lyrics, melody, chords? Definitely. Beats, riffs, bass lines, sound effects? Maybe. Every song is different. There's no one formula that works every time.

Shares