I was in England during the Christmas season of 1987 when Kylie Minogue's first hit, a cutesy-poo version of Little Eva's "The Loco-Motion," became inescapable. I grumbled so predictably whenever it came over the radio or on "Top of the Pops" that the first few notes were enough to get my British then-girlfriend laughing at how much it irritated me.

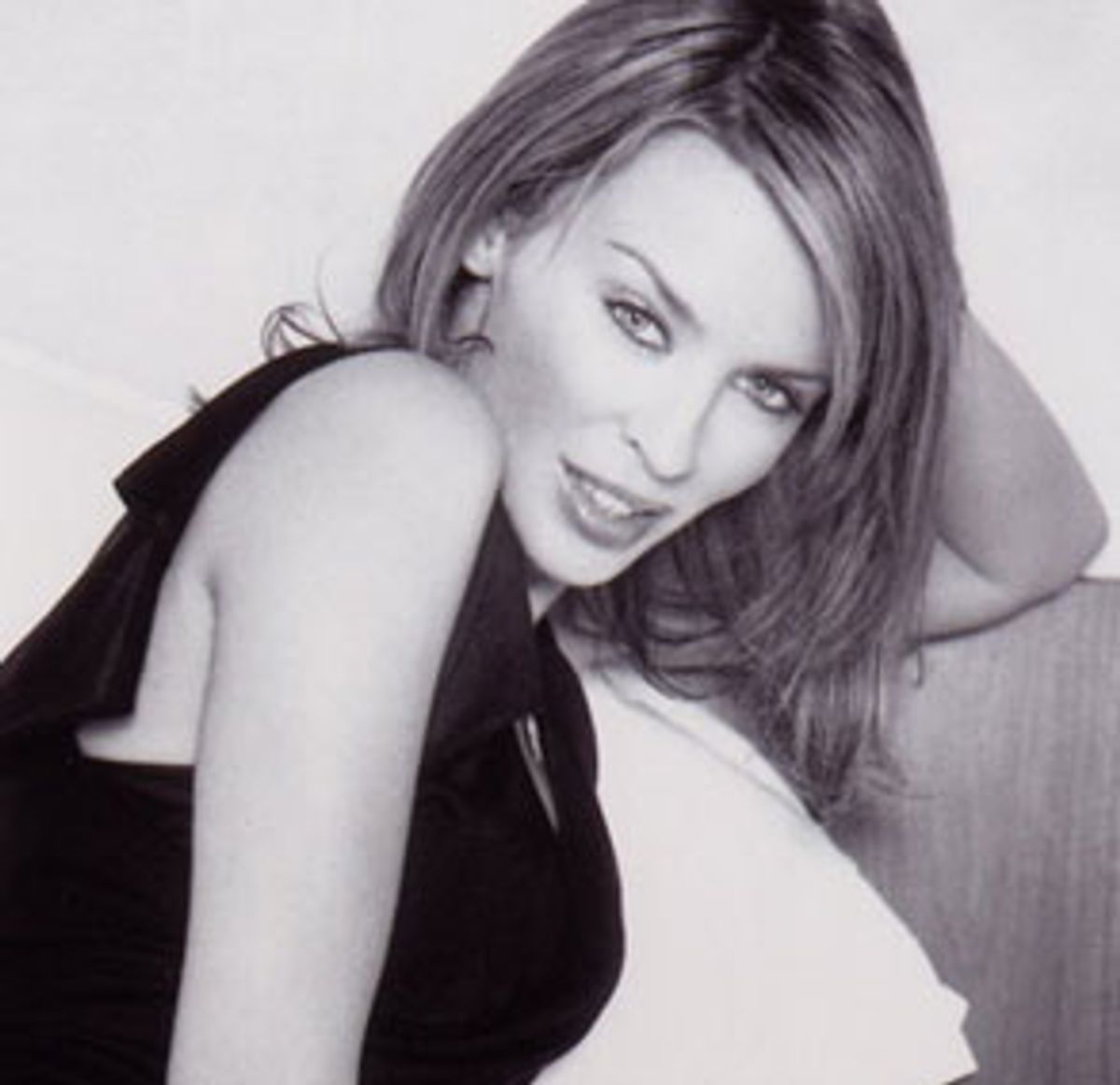

So how, 15 years later, did I wind up standing in line at the Times Square Virgin Megastore, possibly the only straight man in the crowd, waiting for Minogue to autograph "Fever," her new CD? Although Kylie fizzled out in the U.S. after "The Loco-Motion" became a hit here, she went on to a huge career in Europe (30 million-plus records sold), first under the tutelage of Brit-pop schlockmeisters Stock, Aitken, Waterman and then, briefly, in a commercially disappointing fling with alternative rock. But apart from the occasional gossip column appearance, or a photo layout in some Euro lad-mag, in which she didn't look much like the perky teenager in cutoff sweats I remembered grinning her way through "The Loco-Motion," I had barely thought about her.

That is, until early last year, when a Welsh friend returned to New York from a Christmas visit home. My buddy, whose musical tastes overlap with mine, told me that several U.K. critics had listed the Minogue album "Light Years" on their year-end best-of lists. Since British music critics tend to be less embarrassed about the transitory pleasures of pop than their American counterparts (who seem more concerned about writing for the ages), I considered the possibility they might be onto something. But I didn't actually pick up "Light Years" until a couple of months later, after seeing Kylie as the Absinthe Fairy in "Moulin Rouge," a saucier version of that earlier movie sex fantasy, Walt Disney's Playboy Bunny-esque Tinker Bell.

Maybe this is too quirky and personal a reaction to have a lot of resonance. Maybe it's just a result of my own complicated feelings toward music right now. But I don't know if I can convey the sense of relief that swept over me listening to "Light Years." It was the overwhelming pleasure of being able to respond to a piece of pop music immediately, to feel as I were inside its beats even as I was hearing it for the first time, to be ready to hear it again right away as soon as it finished. A big, shiny, friendly piece of retro disco, "Light Years" brings back the utopianism of disco's heyday like nothing in years.

Something about disco has always put me in mind of the most lavish auto show imaginable, the type where scantily clad girls dance around new cars and trucks, showing them off, enticing buyers into the pleasure of material goodies. "Light Years" shares with Daft Punk's "Discovery" a sense of a being a perpetual-motion machine, the beats working like the axles of an 18-wheeler to keep you moving smoothly down the road. Kylie has a small voice -- a sort of nasal sinuousness she puts to good effect -- but "Light Years" was created by people who understand that the pleasure of disco has to do with size, with the hugeness of the thumpa-thumpa-thumpa beats. That's what contributes to the communal ecstasy of disco, the feeling of everyone joined in a party that's just getting happier as it gets bigger. "Light Years" is a travel brochure of a record, devoted to exotic good times.

Minogue's new album, "Fever," just released in the U.S. after premiering in Europe last fall, is a more streamlined version, not so expansive or cheery. A reviewer in Time Out New York noted that "Light Years" was "so gay that it didn't stand a chance in the U.S. pop marketplace." There's something to that. (The crowd gathered at the Times Square Virgin Megastore a few weeks back made it clear that Kylie has a huge gay following. Four male dancers, stripped to the waist, gyrated on platforms as she signed autographs. The two guys in line behind me pronounced these six-pack go-go dolls "scary.") At the risk of indulging a cultural stereotype, saying that a dance record has a gay sensibility is something like saying your watch was made in Switzerland or your shoes in Italy. It means it was put together by people who have perfected the form and know what they're doing.

Powered by the perfectly named single "Can't Get You Out of My Head" (a fate experienced by anyone who hears it more than twice), "Fever" is a little chillier than "Light Years." You might say it's the night lights seen from the back of a passing limo rather than from the crush on the dance floor. What's remarkable about it is how fresh it sounds. The album entices rather than commands your attention. You can put it on and listen with one ear and still find the spirit and rhythm of it carrying you forward, making you want to hear it again. Whether the music is retro-disco or house, there's still a dedication to fun that, for me, makes Kylie stand out. Especially now.

If you're still listening to pop music after you hit 30 (I'm 10 years past that, and still listening), you accept that you go through periods where your attention seems to tune out. Maybe there's too much going in your life to pay close attention, maybe the sheer amount of product is overwhelming, maybe the music -- for whatever reason -- just doesn't speak to you at that moment. Even allowing for all that, this seems to me a weird time for pop.

It's not that there isn't music that still speaks to me. I have rarely been as moved by any music as I was by "The Langley Schools Music Project: Innocence & Despair." Recorded in a school gymnasium in rural Western Canada in the mid-'70s, it's 60 kids with two mikes and rudimentary arrangements, singing their hearts out to a selection of '60s and '70s pop. In other words, it's the very audience these songs were directed to, taking possession of them, pouring their energy and enthusiasm and hopes into every off-key note. And the upcoming self-titled album by the Reputation, an Illinois band fronted by Elizabeth Elmore, late of Sarge, communicates directly. If Elmore's generation (she's in her mid-20s) doesn't feel she's capturing something of their essence in songs like "The Stars of Amateur Hour," it may only be because she cuts too close to the bone to leave anyone feeling comfortable. (The emotional bluntness of the music makes me, at 40, wince.)

And there are battles in pop music right now that I feel like I've already witnessed. Long before the Strokes won me over to their debut album "This Is It," the backlash the band generated pissed me off. It was a variation of the old punk-indie snobbery that decreed that a band receiving major label bucks and media hype just had to be sellouts. I'd heard it in the '80s, when X and then the Replacements signed to major labels and, then as now, the argument has nothing to do with the quality of the music.

And then there's the distance that older pop music fans may feel from the two types of music ruling the charts -- teen pop and hip-hop. (Rap-metal and nu-metal, in fact any kind of metal, might be included, too, but -- with the exception of Metallica -- I can't pretend I have any interest in it.)

In the case of the former, whenever I've tried to listen to Britney, Mandy, Jessica, N'Sync, et al., I can't hear a voice, not even the voice of a producer turning the vocalists into just one more element in the mix. There's an anonymity and -- for all the belly-baring and rump-shaking, all the impossibly low-cut jeans and visible underwear -- a sexlessness to the music that makes me feel as if my ears were sliding off each polished hook. (The exception was a 1999 single that didn't make it to these shores, "Honey to the Bee" by the Brit teen popster Billie Piper, that had a catchiness and salaciousness that Britney can only dream about.)

My feelings about hip-hop are more complicated. For older listeners, hip-hop may feel something like information overload. Trying to work our way into the rhythmic, sonic, and verbal density of the music may make us feel like watching younger kids whiz through computer programs and video games. There seems too much to process for the immediate access pop has always promised. And for me, hip-hop presents another problem: the question of how much, if any, irony is involved. The only answer I've been able to come up with based on my intermittent listening, and it's an unsatisfactory one, is that hip-hop is both a reflection of social realities and a celebration of the worst bling-bling sensibility. There have been albums and artists (Outkast, Q-Tip's "Amplified," the all-but-forgotten Basehead, the first album from Timbaland and Magoo) and singles (the Geto Boys' "Mind Playin' Tricks on Me," a slew of songs by Jay-Z) that I've taken to heart.

But there's a coldness to much hip-hop, a negation of the heart and soul that is the essence of the greatest black pop, that I can't get past. Ja Rule sounds great coming out of the radio or, in my Brooklyn neighborhood, blasting from cars driving by in the summer (last summer, you couldn't get through a day without hearing Jay-Z's "The Blueprint" drifting into the windows at some point). When I slip it onto the stereo, though, I find the deadness of his affect numbing. In the chilling opening of George P. Pelecanos' new novel "Hell to Pay," a dogfight takes place to the sound of "Dr. Dre 2001" playing as the animals rip each other to pieces. Pelecanos is clear in the book that the blame laid on hip-hop for urban violence is a canard, the panicked reaction of nervous people. But in that opening scene you can't escape the implication that the emotionlessness of the young men watching carnage as entertainment has found a fitting soundtrack. Especially in contrast to the '70s soul that plays constantly on the car stereo of the novel's middle-aged black hero.

Kylie Minogue belongs to diva pop, a category that encompasses many styles and performers. And it's a type of music that, in its own way, has had much of the pleasure bled out of it in the last few years. Its ruling eminence remains Madonna. But I have to confess that despite the occasional great single, like "Ray of Light," Madonna has struck me as a great bore ever since, around the beginning of the '90s, she gave up being a trash provocateur and began thinking of herself as an artiste. The change seemed to come in around the time she went on "Nightline" to defend her "Justify My Love" video, a parody of '60s European arthouse cinema (think Michelangelo Antonioni and Alain Resnais redone by a clever exploitation filmmaker), and, without a trace of humor, talked about it as if it were a serious exploration of the limits of sexuality. The "Sex" book followed, as cold as its stamped metal binding. The surprise and delight she once showed in pushing people's buttons had vanished, replaced by a lot of pretentious talk about her "vision."

The diva school has had to weather the effects of Whitney and Mariah and all their progeny, that group of singers who have negated emotional content in favor of vocal gymnastics. Writing in the New York Times Magazine, Rob Hoerburger, one of the most sensitive of the current crop of pop critics (in thrall to the music, he writes to recreate it), refers to them as singers who have abandoned the power of suggestion in order to flog a song within an inch of its life. There have been a crop of singers -- Macy Gray, Alicia Keys (who may have to wage a battle with her own tendencies towards grandiosity), and especially Angie Stone -- who are working to restore the nuance and tenderness of mid-'70s soul.

But the defining quality of diva pop has been the tendency for the singers (and the music press) to treat every new record as if it were a chapter in the psychobiography of the artist. It's a notion that wipes out the very idea of the interpretive singer, and envisions the song less as a vessel for emotional power than a roman à clef to which the celebrity provides the decoder ring. New releases are routinely accompanied by fawning profiles about how the singer overcame great obstacles (the blue thong or the pink one?) to deliver a brave personal statement.

Sometimes there is something to talk about in these records. Janet Jackson (who has turned into a more interesting figure than Madonna, and a maker of better music) did deliver something strong with "The Velvet Rope." It wasn't just the teasing is-she-or-isn't-she lesbian references or S/M stuff, it was in the scarifying "What About," which starts out as a syrupy ballad (replete with the sound of seagulls) before veering into harsh, zigzagging accusations: "What about the times you kept on when I said no more please ... / What about the times you shamed me/ What about the times you said you didn't fuck her/ She only gave you head." But even "The Velvet Rope" didn't go so far into psychodrama that it neglected the velvety pop typified by numbers like "Got 'Til It's Gone" and "Go Deep," songs that kept sounding good on the radio weeks after they debuted. By contrast, Jackson's latest album, "All for You," despite the presence of a few catchy numbers, works largely off of the publicized end of a secret marriage and is an I'm-OK-I'm-just-working-on-myself bore.

The truest sign of maturity and substance I see anywhere in recent diva pop was on Aaliyah's eponymous final album. It was a musical maturity, proof that she had settled comfortably and confidently into the new sound she had been creating with her producer Timbaland on great singles like "Try Again" and the flabbergasting "Are You That Somebody?" Aaliyah's music, as well as her image, was a study in contingencies, sexual without being blatant, insinuating without being demanding, emotional without being melodramatic.

While Aaliyah's death was given the full-blown celebrity news coverage, barely anything was written about her music. (The lone, superb exception was Kelefa Sanneh, an editor at the black cultural journal Transition, in a piece written for the New York Times.) The mainstream press has never been adept at dealing with the significance of rock deaths. Still, the inability to consider Aaliyah as a musical figure (as opposed to just another dead celebrity) shocked me. Part of it was, I'm sure, an age thing on the part of editors and producers, a (not altogether unfounded) belief that she didn't make the type of music their audience would care about. But I can't help feeling that race played a part, that for all the ways in which black music and black-influenced music dominates the pop world right now, the press cognoscenti still don't believe that a black pop artist can be musically significant.

Significance should never be determined by the numbers, by record sales or box office grosses. Yet here was a young woman who had been selling millions of records since she was 15, and more important, had been changing, developing and refining one of the most sophisticated styles in current pop music, who simply didn't exist for the white press. That condescending phrase used to describe the appeal of pop music -- "the little girls understand" -- was, in Aaliyah's case, entirely right. Certainly, the pop audience understood what they lost better than their elders. That's how, even though she sold millions of records, the most sophisticated pop diva to emerge in the last few years still feels like a secret others have yet to catch on to.

It may be significant that Sade, who largely shuns interviews and has, with unshakable confidence, stuck to the same style since her 1985 debut, still makes records that, maybe because they retain some mystery or maybe because she's smart enough to hold something in reserve, are durable and pleasurable months after their release. Instead of overpowering you with diva drama, Sade makes some space for the listener to enter into the music, to uncover it slowly.

As successful as Sade is, she's an anomaly next to the likes of Mary J. Blige. Blige has made some good, showy pieces of emotionally pushy diva soul. It was hard, though, not to watch her recent Grammy performance of "No More Drama" and think: What is she talking about? Mary J. Blige proclaiming "No More Drama" is like Soupy Sales proclaiming "No More Pies." Drama is her raison d'être, and not the fat, juicy theatrics of singers like Teddy Pendergrass or Thelma Houston, who aimed to live up to the melodrama of their numbers. The tension in their performances derived from the question of whether they'd be able to stand up to the florid emotionalism they created around them; the excitement of their performances was that they did.

The great examples of diva drama in the last few years have gone largely unheard: a Vegas performer named Kristine W.'s first album -- another retro-disco special -- called "Land of the Living," which had one of the hugest sounds dance music has produced since the '70s, with a voice to match; and especially Billie Ray Martin's "Deadline for My Memories," a Gothic cathedral of dance music, brooding, paranoid, slightly forbidding and thrilling. Both Kristine W. and Martin know how to build a song, know enough not to give everything away from the first note. So that by the time the singer reaches full throttle, there's an overwhelming sense of release. These records (can you even get them anymore?) are melodrama as performance, not as self-analysis and self-display.

Neither "Light Years" nor "Fever" offers a single clue to Kylie Minogue's psyche, personal life or current romantic status. While she looks poised to finally extend her stardom to America, there are some who think that what they see as her impersonality will stand in the way. Writing about her in the New York Times, J.D. Considine said, "American audiences prefer self-defining divas on the order of Mariah Carey and Madonna. After all, both Madonna and Ms. Carey write or co-write their own material and have created some of their biggest hits by drawing from their own inner struggles." Uh-huh. Does anyone doubt that the next Mariah Carey record, coming after her much publicized nervous breakdown, the flop of her movie "Glitter" and the commercial disappointment of her last two albums -- which led to a buyout from her enormous recording contract -- will be its own Vanity Fair profile, a chronicle of her brave comeback after the sort of "inner struggles" Considine writes about?

It's not that there's no reason to look for the personal content in diva albums. For too long, mostly white rock critics ignored the personal content of soul music (especially Philly-influenced '70s soul) while parsing everything that flowed from the pen of St. Joni (or, God forbid, Janis Ian) for driblets of wisdom. But in diva pop, self-promotion has too long passed for personal statements. In that atmosphere, it's no wonder that singles like Nikka Costa's "Like a Feather," with its borrowed '70s funk-isms, or the bad-girl brattiness of Pink's "Get the Party Started" (and its terrific video) with its "get da fuck out my way" confidence, sound so great.

And it's why Kylie Minogue offers so much uncomplicated pleasure. What some people hear as impersonality, I hear as professionalism, a dedication to the spirit of fun and community and release that has always been at the heart of dance music. "Fever" kicks off with "More More More" (not the Andrea True Connection hit of the '70s) and the title gives the game away. For all the cool control of her voice (and of the sound of the record in general) there's an appetite at work here, a generous appetite.

"Fever" is about a determination to give the listener a good time, to make sleek, catchy dance pop in which nothing -- neither the vocals nor the sexuality projected by the singer -- overwhelms the sound as a whole. "Fever" allows you to relax, in the way you can when you know your enjoyment is in the hands of people who aren't going to screw it up. The hooks arrive on schedule; the beat and, more important, the swirl of the music keep returning to stir you into the mix. It's strange to speak about an album that is a bid for U.S. stardom as self-effacing. But in terms of what her contemporaries are doing, Minogue, who's now 33, hasn't let her ego get in the way of the music.

A Time Out profile quotes alt-rock legend Nick Cave, a fan who performed a duet with Kylie on his album "Murder Ballads," saying that her music takes place in "that space between innocence and sensuality that is the playground of all great pop music." I don't know if I'd go so far as to say that Minogue has made great pop music. It may be that "Light Years" and "Fever" are just passing pleasures, although that's nothing to sneer at. But Cave's image of the music as taking place on a playground feels absolutely right, a playground that magically expands to encompass whoever listens and wants to join the game.

Shares