Scandal in American public life follows a script as predictable as pornography. First come the initial scanty press reports. Then the "He/she/they said/did what?" reaction from the disbelieving public. After that the backlash, both condemnation and defense. And ultimately, in a carefully selected media forum, the public mea culpa.

This final act is what was supposed to have played out last week on ABC's "Primetime Thursday" during Diane Sawyer's hour-long interview with the Dixie Chicks. Except for one thing: The Chicks weren't following anybody's script but their own. Over the course of the interview, filmed in band member Martie Maguire's Austin, Texas, home, Maguire, her sister Emily Robison and Natalie Maines, whose March 10 comment from the stage of London's Shepherd's Bush Empire -- "Just so you know, we're ashamed that the president of the United States is from Texas" -- started the controversy that continues to engulf the trio, the three refused to back down.

Forget the apology Maines issued to Bush a few days after the Associated Press first reported her words, or the stories that her comments had brought the band to the point of dissolution. Offered the chance to take it all back and make nice, the Dixie Chicks instead chose to turn the interview around. Sawyer wanted answers; the Chicks offered questions, hard questions. Sawyer wanted to talk about the damage they may have done to their career; the Chicks talked about the damage being done to America in an era where Vice President Dick Cheney has proclaimed "You're either with us or against us."

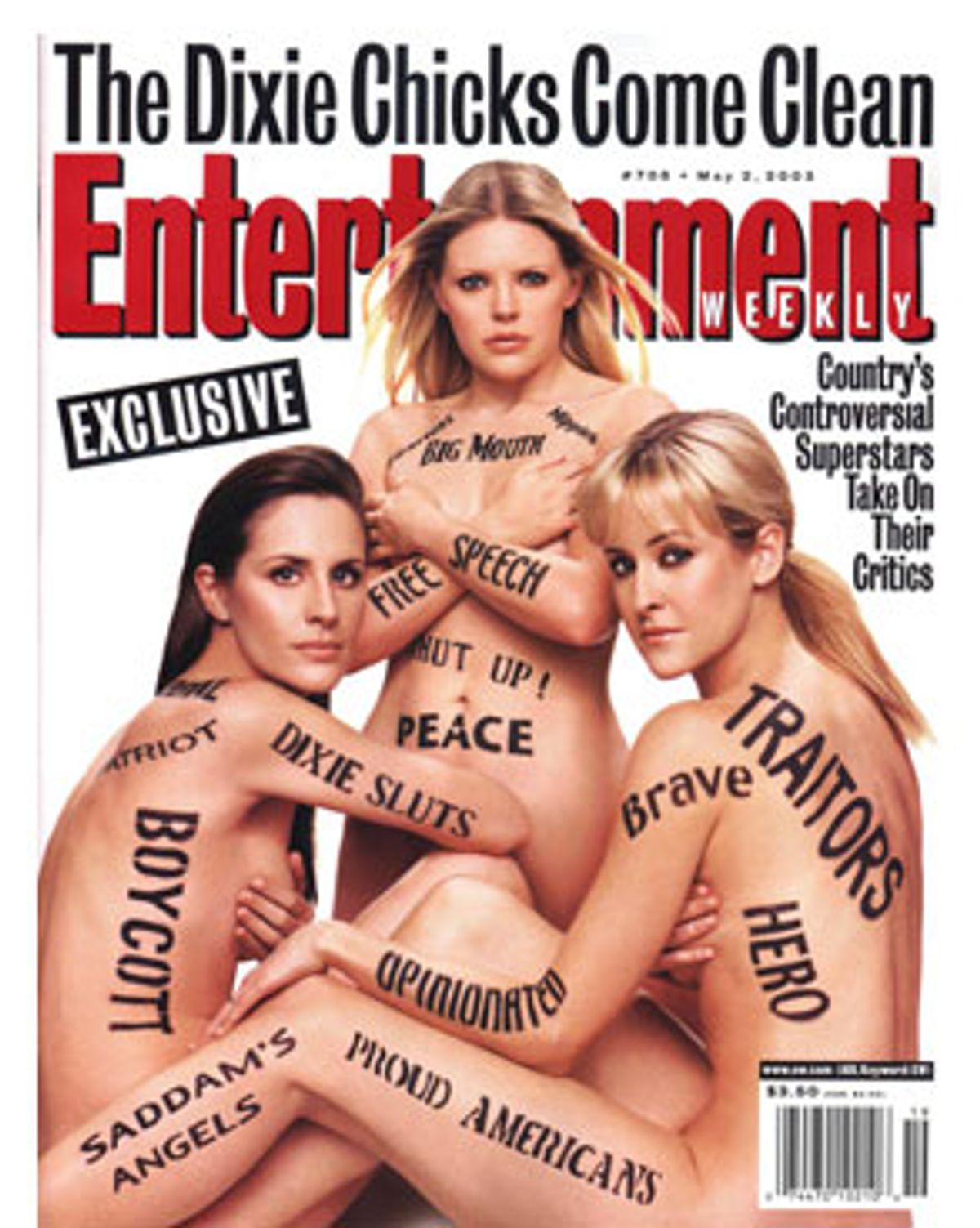

The band may have gotten more attention posing nude for the cover of the current Entertainment Weekly, with phrases like "Dixie Sluts," "Saddam's Angels" and "Traitors" stamped on their bodies. But it was the stubborn refusal they showed Sawyer that cut deepest. Yes, Maines, as she did in her apology, said that her statement was "disrespectful" and "the wrong wording with genuine emotion and question and concern behind it." But she didn't apologize for those questions. "I ask questions. That's smart, that's intelligent, to find out facts," she said.

The sisters, Emily and particularly Martie, not only defended Maines but amplified her comments. Given an hour for prime-time damage control, the Dixie Chicks instead stopped the network cheerleading for the war dead in its tracks and expressed the honest confusion many people are feeling far more effectively than any of the strident rhetoric that has emanated from the left as well as the right.

With the Chicks not following the preset P.R. script for smoothing over a public brouhaha, it was up to Sawyer to provide the pornography. You couldn't find it in her connecting narration, which was simply the typical pap that passes for writing in television journalism -- "Freewheeling ... high-spirits ... the famously untamed lead singer ... the rebel daughter of a renowned steel-guitar player ... the refined sisters ... in that friendly, country way, we know all about their lives ... There would be frightening threats, towering rage, in the words of another of their hit songs, a landslide." The pornography came from the way Sawyer, frustrated in her attempt to offer the band up for ritual sacrifice, chose to stand in for the bullies.

Since Maines' comment, the band has received death threats and had round-the-clock security posted at their homes. The people who attend their upcoming concert tour will have to pass through metal detectors. The threats haven't just come from yahoos, like the caller to a radio show heard during the "Primetime" interview who said, "I think they should send Natalie over to Eye-rack, strap 'er to a bomb, and just drop 'er over Baghdad." A San Antonio DJ claimed to know where Maines lived and said a posse should go over to her house and straighten her out. And in South Carolina, where the band will open its tour later this week, a legislator rose in the state assembly and said, "Anyone who thinks about going to that concert ought to be ready, ready, ready to run away from it."

Sawyer didn't descend to this level of bullying. And she didn't adopt the strategies of the higher thugs like Bill O'Reilly, who simply talk their opponents into submission. Sawyer's tactics were subtler, more insidious. Instead of journalist, the role Sawyer chose to play was the junior high school principal who aims to shame you into jelly with a combination of starch and steel.

From the beginning, Sawyer aimed to put the Dixie Chicks in their place. She began the show by saying, "They're not exactly the people your civics teacher would expect to find at the center of a raging debate over free speech in America." These are just country singers, after all, she was saying. Who would expect thought from them? And then, at every turn, the Dixie Chicks simply outthought Diane Sawyer.

Instead of playing a plea for forgiveness, the interview played out as a drama between two sharply different views of what it means to be an American citizen. There was Sawyer's view, in which only certain people are qualified to speak their minds, and the view of the Dixie Chicks, a vision shot through with contingencies and uncertainties far more complex than Sawyer could process. "I guess on some level I feel like me speaking out, not only that particular statement, but here today, is the most patriotic thing I can do," Maines said.

Schoolmarm Sawyer wasn't having it. The aghast subtext of nearly every question was, "I knew you were spirited girls, but what could you possibly have been thinking?" It was all faux, of course, the journalist as devil's advocate, but Sawyer's condescension was real, certainly not ameliorated by her midshow comment that she grew up in Kentucky and loves country music. It reached a pinnacle of sorts when Sawyer repeated Maines' comments and asked, "Ashamed? Ashamed?" as if contrition were the only appropriate response to questioning the president of the United States. And when she didn't get contrition from Maines, she turned on Maguire and Robison, expressing disbelief that "neither of you listening to [Maines' remarks]" were shocked, as if they had all just taken part in the locker-room scene from the movie "Carrie."

Finally, Sawyer said, "I feel something not quite wholehearted when you talk about apologizing for what you said about the president." It's a moment that can stand with the great scene in Frederick Wiseman's documentary "High School," when a teacher rejects a young boy's apology because "There's no sincereness [sic] behind it." This was the assertion of an authority that aims to strip its target of all self-respect, all ability to think for themselves.

The trouble, though, with playing devil's advocate as enthusiastically as Sawyer did is that you begin to ape the nonthought of the role you are playing. Setting the stage for Maines' comments, Sawyer talked of the week before the war started and said, "Seventy percent of Americans were clear that the protesters were wrong." Look at the language. Not "Seventy percent of Americans expressed the opinion that the protesters were wrong," but "Seventy percent of Americans were clear that the protesters were wrong." Case closed. And then later, "But even people who said it's fine to question the war were shocked that someone would stand on a stage and attack the commander in chief." Certainly that is what many people felt. But Sawyer presents the shock as if it were logical. It's all right to question government policy -- which, in Sawyer's formulation, somehow comes into being of its own accord -- but not the person who formulates the policy and puts it into action. And not "the president" but "the commander in chief."

Sawyer seemed on a personal mission here to defend George W. Bush. Maines said, of the buildup to war, "I had a lot of questions that I felt were unanswered," and later, "I just personally felt like, 'Why tomorrow?' It's not like I don't ever want you to go over there ... why can't we find the chemical weapons first?" Sawyer then asked, if they were against the war, what they would have done about Iraq. Calling it an unfair question, Maguire said it was not her place to make foreign policy decisions. Sawyer replied, "If you're going to criticize the president for his own decision, you'd better have your own."

It was a damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don't moment. Had Martie Maguire presumed to articulate what she thought should have been U.S. policy regarding Iraq, she would have let herself in for comments of the "What does a country singer know about war?" school. Instead, affirming her right as a citizen to criticize the policies of her government, she got pretty much the same response from Sawyer: "If you're going to criticize the president for his own decision, you'd better have your own." Since when is a citizen who criticizes her government required to have an alternate solution?

Had Sawyer been interviewing someone who supported the war, she wouldn't have felt the need to ask what battle plan they believed the Pentagon should have adopted, and it would have been ludicrous if she had. But obedience to power would not, in Sawyer's view, have necessitated such a question. It's not surprising then that after Maguire read this quote from Theodore Roosevelt, "To announce that there must be no criticism of the president or that we are to stand by the president right or wrong is not only unpatriotic and servile but is morally treasonable to the American public," the camera simply cut away. There was nothing Diane Sawyer could say to that.

One of the remarkable things about the interview was the Chicks' lack of invective -- toward the troops, toward people who supported the war and even toward Bush. What they expressed about the president was honest disappointment. At one point, Maines imagined what she would have liked to have heard Bush say about the protesters. "You know," she imagined the president saying, "I saw them. I appreciate the sentiment that they're coming from. I appreciate that these are passionate citizens of the United States. But I feel, I really feel, that this is the right thing to do." Sawyer attempted to counter by saying the president had affirmed the right to protest.

But the clip that followed, of Bush on March 6 following worldwide antiwar protests, told a different story. Dripping contempt, Bush said, "First of all, size of protests, it's like deciding, well I'm going to decide policy based on a focus group." It's the perfect distillation of the arrogance of the Bush administration, reducing the fears and concerns of people all over the world to "a focus group." It's exactly what Maguire meant when she said, "I felt like there was a lack of compassion every time I saw Bush talking about this ... for people questioning this, for people about to die for this on both sides."

At one point in the interview, Maines said, "People have died to give you this right. That's what I'm doing. I'm using that right." But she is speaking at a particularly ugly time in American history, when using that right is enough to get you branded a traitor. As Dick Cheney has said, "You're either with us or against us."

"That's not true -- it's not true," Maines said of Cheney's comment. Though to many Americans, it is true. This weekend, I was walking through the central New York town of Clinton and came upon a flier in a store window for a rally in support of the troops. The legend on the top of the flier read "Loyalty Day." The meaning was clear: If you don't support the war, you're a disloyal American.

This is what public discourse has come down to in America right now. The litany is depressing and familiar, from Ari Fleischer's admonition to Bill Maher after 9/11 that Americans have to watch what they say, to the suspension of habeas corpus for thousands of people who've been arrested, to the even more onerous dissolution of civil liberties that would come under the PATRIOT II act. In the New York Times on April 27, Thomas Friedman wrote, "It feels as if some people want to use this war to create a multiparty democracy in Iraq and a one-party state in America."

And it cuts both ways. The left in no way holds power in America at this moment, but its vision of what politics should be often seems to partake of the same either/or dogmatism. In the current issue of Dissent, Michael Wreszin writes in response to an article by Michael Kazin, which he feels exemplifies the dangers of the magazine's belief that the left should speak "patriotically to our fellow citizens."

Wreszin writes, "Anyone seriously engaged in activist politics wants to develop a constituency and see it grow. But did Kazin expect [Martin Luther] King to communicate with the average white citizen in racist Mississippi and Cicero, Illinois?" The vision of politics that this statement reveals is remarkable. Wreszin apparently believes that Martin Luther King was preaching only to the choir, that he didn't try to communicate to the people who disagreed with him. (How then, you wonder, did he expect to change anything?) It's the opposite of the belief that politics is about engagement, and an affirmation of a politics that speaks only to true believers. In other words, it's a rejection of everything that it reasonably means to be political.

As much as I loathe the determination of the Bush administration to use the threat of terrorism to abolish civil liberties and create a government that feels it has no obligation to disclose the reasons for the decisions it takes, you can understand why people buy into that when you see protesters holding signs equating Bush with Saddam, or the placard shown in footage during "Primetime" that read "Bombing Is Terrorism." Real politics are not possible when people abdicate the responsibility to think in favor of ideology, because ideology is always the enemy of thought.

This is the atmosphere in which Natalie Maines chose to speak out. And it's the atmosphere in which she and Martie Maguire and Emily Robison maintain that their questioning of the government and of Bush's willingness to respect the opinions of others marks them as good patriots.

It's not just the clarity and persistence of what they've said that marks their bravery, but who they are. As "Primetime" pointed out, they are hardly the only celebrities to have spoken out against the war. The show noted that Susan Sarandon had been disinvited from a United Way fundraiser, and that her partner, Tim Robbins, had been barred from a celebration of "Bull Durham" at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. But nobody is bulldozing cassettes of Sarandon and Robbins' movies, or Sean Penn's, who took a trip to Iraq a few months back. Nobody is boycotting "The West Wing," although Martin Sheen is a longtime activist. And nobody is burning Michael Moore's book "Stupid White Men." Not to suggest that those celebrities haven't taken grief, but it's no surprise when Sarandon or Robbins or Sheen or Moore speak out against the war. That's a logical action, given their very public politics.

But none of these people reach as wide an audience as the Dixie Chicks, who are the biggest-selling female recording artists of all time. When my Salon colleague Stephanie Zacharek wrote a few weeks back that the backlash against the Chicks was certainly due in part to the traditional conservatism of country music, she got letters accusing her of painting country fans as a bunch of ignorant hicks. Those responses fail to take into account the simple fact of the disapproval that has traditionally been leveled at country stars who don't toe the line.

In the '60s, after saying he was a fan of the Beatles and recording versions of Chuck Berry's "Memphis" and "Johnny B. Goode," Buck Owens took out an ad in a Nashville fan magazine called "Pledge to Country Music" where, among other things, he said, "I Shall Sing No Song That Is Not a Country Song." Johnny Cash alienated many country fans with songs like "The Ballad of Ira Hayes" and later protest numbers like "Man in Black" and "Singin' in Vietnam Talkin' Blues" (an amazing song that has much to say about how you can be against a war and care about the safety of the troops). That didn't fit in with a format where a song like Merle Haggard's "Okie From Muskogee" (reactionary as hell and still a great song) could he a huge hit, or where, at the height of Watergate, Nixon was welcomed by Roy Acuff onto the stage of the Grand Ole Opry.

The simple fact is that country plays to a huge demographic, and often an older one, and the majority of Americans support the war. It was inevitable that the Dixie Chicks were bound to have, among their fans, people who would be upset by any antiwar statements. In the "Primetime" interview, Maguire talked about trying to convert friends to country music, people who said, "That's redneck music, those people are so backward and conservative." It was obvious how that attitude pained her. But it's hardly painting a large segment of the country audience as rednecks to acknowledge the conservatism of country music.

"It's all about being country-music artists," Maguire told Entertainment Weekly. "And [country radio not playing our music] is proving that it is about country music." Maguire told Sawyer of their colleagues in country music, "I was surprised at how many would come forward but didn't want to come forward publicly." Among the things reported in the Entertainment Weekly cover story was the fact that Vince Gill has had his patriotism questioned for saying it was time to lay off the Dixie Chicks. EW also reported that Toby Keith projects a doctored image of Maines with Saddam Hussein during his stage show, and that Travis Tritt, that mullet that passes for a man, has called the band "cowardly."

On March 20, RCA Nashville publicity sent out an e-mail headed "Sara Evans Voices Her Views in Glamour Magazine," in which the country singer is quoted as saying, "I trust [President Bush] to do whatever is necessary to protect our nation from al-Qaeda, Saddam Hussein and other terrorists. It's disheartening to me to hear negativity about our President during this highly critical time -- and it is especially disheartening to hear comments made outside the United States. Republican or Democrat, we have an immediate duty as Americans to rally around our President and troops." Wonder who she was talking about?

For all the talk about how the Dixie Chicks have destroyed their career, people haven't pointed out (or pointed out tangentially, as Sawyer did) that "Home" is still No. 3 on the country charts and selling about 33,000 copies a week, and that most of the shows on their upcoming tour have sold out. It makes no business sense for country radio to ban the band, but I think that the boycott was just the excuse that country radio was looking for to stick it back to the Dixie Chicks. The trio had already challenged the format with "Long Time Gone," the first single from "Home." One of the verses went "We listen to the radio to hear what's cookin'/ But the music ain't got no soul/ Now they sound tired but they don't sound haggard/ They got money but they don't have cash/ They got Junior but they don't have Hank."

Since the Chicks were the biggest stars in country, country radio had no choice but to play a single that slammed most of the music it played as prefab and anonymous. "Country music doesn't need the Dixie Chicks," said one caller to a radio show heard on "Primetime." But since the band has proved a huge crossover success, and did it with an album more "country" than their previous two, country music may find that it needs the Chicks more than they need it.

Given their huge success -- which shows no signs of dissipating -- you have to be a special kind of ass to claim, as some have done, that all this has been a bid for publicity. The biggest stars in country music didn't need publicity, especially coming off an album that debuted at No. 1 on the pop charts and stayed there for weeks. You would have to be very cynical or very stupid to believe that anyone would choose the kind of publicity that would bring them death threats.

Still, it seems to me that the Dixie Chicks are operating now less in the realm of country music than they are in the realm of punk, which, in his book "Ranters & Crowd Pleasers," Greil Marcus called "infinitely more than a musical style, period ... an event in a cultural time [that was] an earthquake ... throwing all sorts of once-hidden phenomena into stark relief." The Entertainment Weekly cover, another example of how the band has refused to affect the demure pose that would prove they are backing down, appropriates the tactic used initially by the Riot Grrrl bands, who appeared onstage with words like "Bitch" and "Slut" scrawled on their midriffs. Again, it is impossible to divorce the courage of the Dixie Chicks' stance from the place they occupy in mainstream pop.

I don't mean to lessen the determination to find their own voice that characterized riot-grrrl bands like Bikini Kill, and Heavens to Betsy, Excuse 17, and that still characterizes Sleater-Kinney. But the fringe offers a safer place for people to pursue that voice. As the Dixie Chicks have seen, there is more at stake for mainstream performers who decide not to play by the rules. Implicitly, they call everything around them into question. And so it seems a harbinger when you go back and listen to "Home" and hear Natalie Maines sing "You don't like the sound of the truth/ Coming from my mouth ... I don't think that I'm afraid anymore to say that I would rather die trying," or see the roadside sign on the back of the CD booklet "We Are Changing the Way We Do Business."

But it's not just the terms of their own success, or even the terms of pop music, in which the Dixie Chicks are causing tremors. It's the very terms in which public discourse is conducted -- or not conducted -- in America at the moment. "The people who are calling for a boycott are also exercising their right to free speech," some are bound to write to me. Of course they are. But I question anyone's dedication to free speech when they express it by trying to shut down other voices -- not by engaging them or debating them or making a case why they're wrong, but just trying to shut them down. "In wartime only the clandestine press can be truly free," Marcus wrote in an earlier essay about punk. For all the willingness of the mainstream press to roll over and frolic at the feet of the Bush administration, for all the ways in which Bush and Ashcroft are using the Constitution as a piece of toilet paper, I do not believe that a fascist takeover is imminent in America. That is an excuse to shy away from the work that needs to be done to defeat Bush and restore the civil liberties he has trashed.

What I do believe is that for all the fear in the air, fear of the terror without and the repression within, there is also open to us at this moment the chance of exhilaration. Freedom may never seem so alluring as when it is most threatened, when the Republic reaches a moment where, as Norman Mailer wrote in 1968, it can bring forth "the most fearsome totalitarianism the world has ever known ... or a babe of a new world brave and tender, artful and wild." There's exhilaration in any moment when the country has the choice of living up to either the best or the worst version of itself. I'm grateful to the Dixie Chicks for reminding us of that exhilaration, for carrying on, aware of the social limits that have been placed on doubt and dissent, and still insisting that questioning and digging for facts are the mark of patriotism.

That was the freedom offered by the civil rights movement, and it's one of those voices I hear now, the voice of Fannie Lou Hamer, delegate of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, addressing a committee at the 1964 Democratic Convention in Atlantic City, N.J., to challenge the seating of the state delegation elected under the system that prohibited many blacks from voting. "Is this America?" Hamer asked. "The land of the free and the home of the brave? Where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hook, because our lives be threatened daily?"

The comparison only goes so far. As rich pop stars, the Dixie Chicks have security options open to them that were not open to Hamer and the other people working for voters rights in Mississippi. But when people fantasize about strapping Natalie Maines to a missile headed for Baghdad, when a state legislator suggests that anyone who thinks about going to a Dixie Chicks' concert better be "ready to run" (from what -- a lynch mob?), when it's held that you cannot question a war and still desire the safety of the troops, when you're told that it's OK to question policy but not the president, Hamer's question remains. Is this America? The thrill, and maybe the sorrow, of the months to come will be finding out.

Shares