Somewhere around the fourth or fifth time I listened to Bob Dylan's new album, "Love and Theft" -- after I'd finished being distracted by all the musical influences and had begun paying attention to the voice and hearing some of the words -- a 30-year-old memory surfaced: In the middle of an LSD trip I had begun to worry that my identity was dissolving or flying apart, and as a test I decided to sign my name. I was relieved to see that my signature was exactly the same as usual. And then it occurred to me how silly my worry had been. The truth was, I realized, that my "signature" was so tenacious it would be quite difficult, perhaps impossible, to get rid of even if I wanted to. After all, how many people (I would become one of them not long afterward) spent years in psychotherapy trying to change their signatures just a little bit?

From the earliest years of his career Bob Dylan has had a passionate impulse to obliterate his personal identity. That passion has, at various times, been reflected in his biographical mythmaking, his allergic reaction to his celebrity, his flirtations with religion, his compulsion to confound the expectations of his audience by constantly transforming his persona. (In the process he has often denied that the previous incarnation ever existed: Who, me? Political? A folksinger? A poet? An outlaw?) And ever since "John Wesley Harding" -- his dramatic 1967 switch to acoustic "folk songs" that sound more like comments on "the folk song" -- much of his work has been defined by an apparent desire to unload the baggage of his own experience and become a vessel, channeling American Music.

Of course, the counterimpulses have also been strong: Dylan has an indelible signature, not to mention an indelible ego. The essential tensions in his music have never been about electric versus acoustic but about personal and idiosyncratic versus collective and generic; topical and profane versus primordial and sacred; transcendence as excess versus transcendence as purgation; "Blonde on Blonde" versus "John Wesley Harding"; "Blood on the Tracks" versus "Time Out of Mind."

I've always had reservations about Dylan's post-"JWH" attempts to get out of his skin, from the homage to country and western of "Nashville Skyline" to the cult of impersonality in the perversely named "Self Portrait" and his hermetic '90s renditions of old folk songs better left to ethnographers. In "Time Out of Mind" -- an album I found virtually unlistenable at the time it came out to near-universal acclaim four years ago and have only now, and grudgingly, come to admire -- it struck me that the self-abnegating impulse had doubled back on itself and become a particularly unpalatable form of megalomania, wherein the listener is buttonholed and forced to become a surrogate for the singer's elusive lover or muse.

"Love and Theft" takes up the quest for anonymity in a quite different way, or so it seems at first. It is mostly pleasant to listen to, yet its self-conscious, let's-give-them-a-tour-of-the-genres schtick is annoying: The first time Dylan did this, in 1970 on "New Morning," there was arguably a real need to nudge parochial rock and folk fans to stretch themselves and listen to other Americas; here it merely feels like an invitation to critics to parade their musical erudition. Sifting through this album's combinations and permutations of blues, country, honky-tonk, swing, r&b, Tin Pan Alley pop, soul, was that a Chuck Berry riff?, etc., etc. -- is certainly a fun game, but the best kind of eclecticism (of which Dylan's corpus is replete with examples) is still the kind that doesn't call attention to itself, that instead creates a whole greater than its parts.

Still, as I said, the game is only temporarily distracting. Soon individual songs begin to break from their generic moorings like Avalon rising out of the mist: the plangent "Mississippi"; the ominous "High Water," punctuated by background rumbles and crashes; "Sugar Baby," with its funereal echoes of "Old Man River" and the traditional "Look Down, Look Down that Lonesome Road." Then Dylan's voice hits me, not pleasant at all. It's beyond raspy, it's laryngitic, maybe consumptive, it sounds some of the time like it's coming from a great distance, through a wind tunnel or something, it's fuzzy. Stuck in the vinyl era, I keep wanting to brush away the lint from an imaginary phonograph needle. It's as impersonal as static or the coughing in a hospital ward, except that every now and then there's an echt-Dylan phrase or inflection to remind us of that signature, scrawled like graffiti into musical concrete.

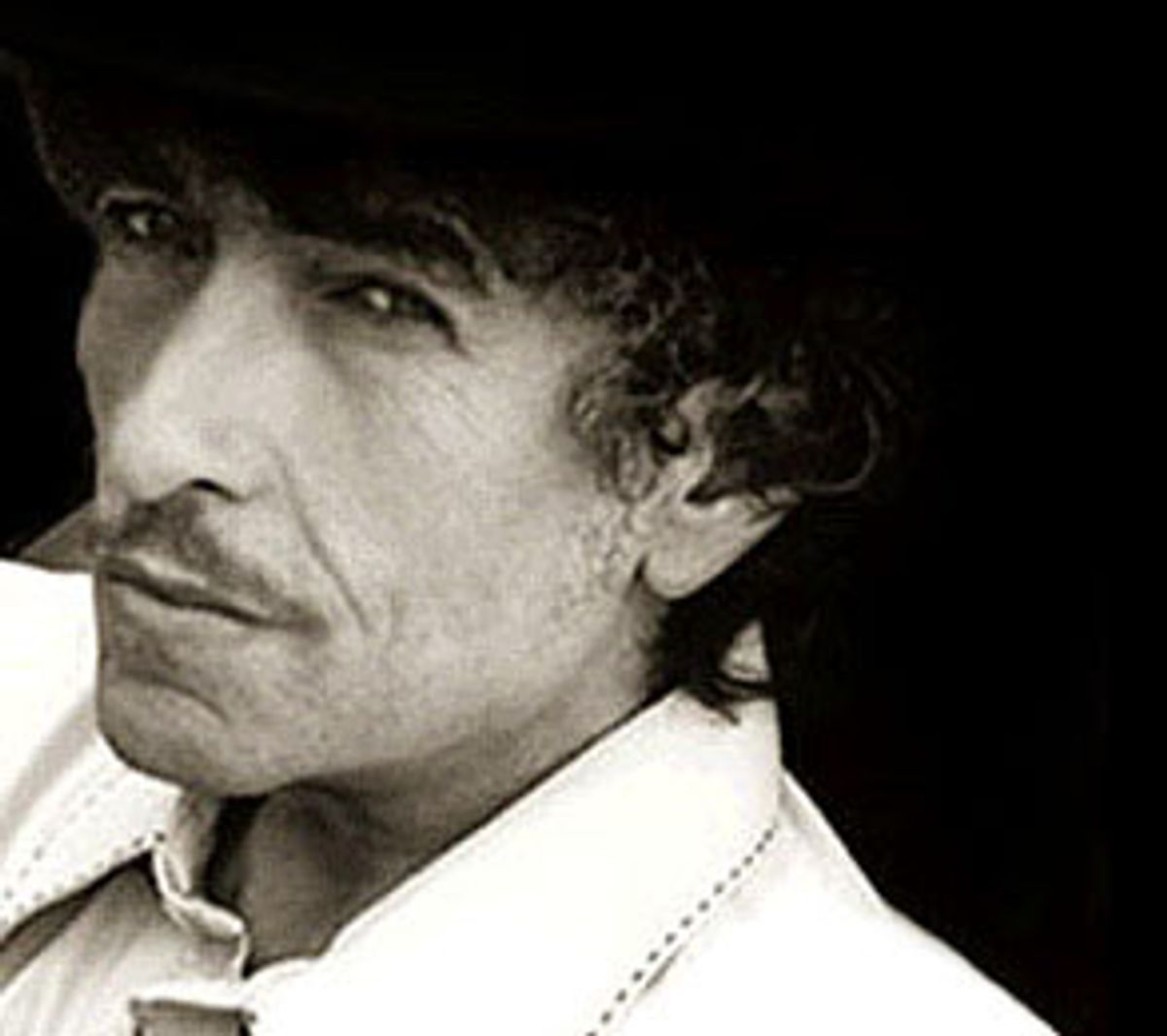

I take another look at the CD cover: the front has Dylan unadorned, vulnerable, looking hardly different -- faint mustache, lined face, bags under the eyes notwithstanding -- from his pictures in the '60s; flip the album over and you get some kind of Mexican bandito, whose mustache, along with white hat and quarter-smile, serves as a disguise. Dylan is hardly there at all.

But it's the lyrics, finally, that make "Love and Theft" what it is -- an album in which the individual and the generic, the topical and the timeless, merge with maniacal intensity: "New Morning" crossed with "Time Out of Mind," juiced by turns with opium and speed. Talk about prophetic: "Every moment of existence seems like some dirty trick/ Happiness comes suddenly and leaves just as quick/ Any minute of the day the bubble could burst ...." And: "I'm stranded in the city that never sleeps ... / Some things are too terrible to be true ... / The sun in the city leavin' at 9:45/ I'm having a hard time believing some people were ever alive." And: "Oh who knows who the bell tolls for, love/ It tolls for you and me" (that one rolling with the jaunty beat of the New Morning-ish "Moonlight"). And: "High water rising, shacks are slidin' down/ Folks lose their possessions, folks are leaving town .... / Things are breakin' up out there/ High water everywhere." And: "George Lewes told the Englishman, the Italian and the Jew/ You can't open up your mind, boys, to any conceivable point of view/ They got Charles Darwin trapped out there on Highway 5/ Judge says to the high sheriff, I want him dead or alive."

If Dylan manages to predict the next day's news by once again tapping into the language of millennial apocalypse, he also captures contemporary anomie (his own, ours) by inventing a narrator -- or narrators, it's hard to tell -- who descends into the hell, or purgatory, or limbo, of America's mysterious rural past, which seems to be located mainly in the south. Contemplating the "earth and sky that melts with flesh and bone," "goin' where the wild roses grow," following the southern star, crossing rivers, staying in Mississippi a day too long, staying with his not-real Aunt Sally, dreaming of Rose's bed, proposing to marry his second cousin, our hero (or is it heroes?) (or anti-hero/heroes?) walks the line between love and battle, not that there's much of a difference. Between "Don't reach out for me, she said/ Can't you see I'm drowning too?" and "Sugar baby get on down the road, you ain't got no brains nohow/ You went years without me, might as well keep goin' now" falls a manifesto of sorts: "I'm not sorry for nothing I've done/ I'm glad I fight, I only wish we'd won." By the end, the topical is slowly submerged as the timeless closes over our heads.

It's seductive stuff, at moments as compelling as anything Dylan has ever done. And yet I find myself resisting. Something is missing, as it was in "Time Out of Mind": the irony Dylan once used to undercut his romanticism and his I-am-America self-importance -- and not least to befuddle the audience that had taken his latest posture too literally. Since you can't get away from yourself, not really, at some point you have to come to terms with that or become delusional.

In post-Sept. 11 America, the inescapably topical is also enveloped in history and myth. In the gap where the towers used to be rise many ghosts: of our Cold War alliance with the Afghan mujahedin, the Gulf War, the fatwa against Salman Rushdie, the Iranian hostage crisis, Vietnam, the Israeli-Arab War of '67, World War II, Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima, World War I, the Civil War, the American Revolution, and beyond, back before the New World, the New Eden, was envisioned. The American imagination will be taxed with demands for unquestioning unity and generic patriotism, will be burdened or inspired by our sense of loss and defiance, identification and separateness, new tensions between individual and collective. And irony (which in some quarters has been prematurely pronounced dead) will be very, very important. The Dylan line that suits does not appear on this album. Better to go back to the beginning, to "Talking World War III Blues" with its teasing ode to mutual paranoia: "I'll let you be in my dream, if I can be in yours." Like the Woody Guthrie songs that were its inspiration, it shamelessly appropriates traditional form for contemporary purpose, and its coda is "I said that!" with the accent on the "I." You can't get any more mythically American than that.

Shares