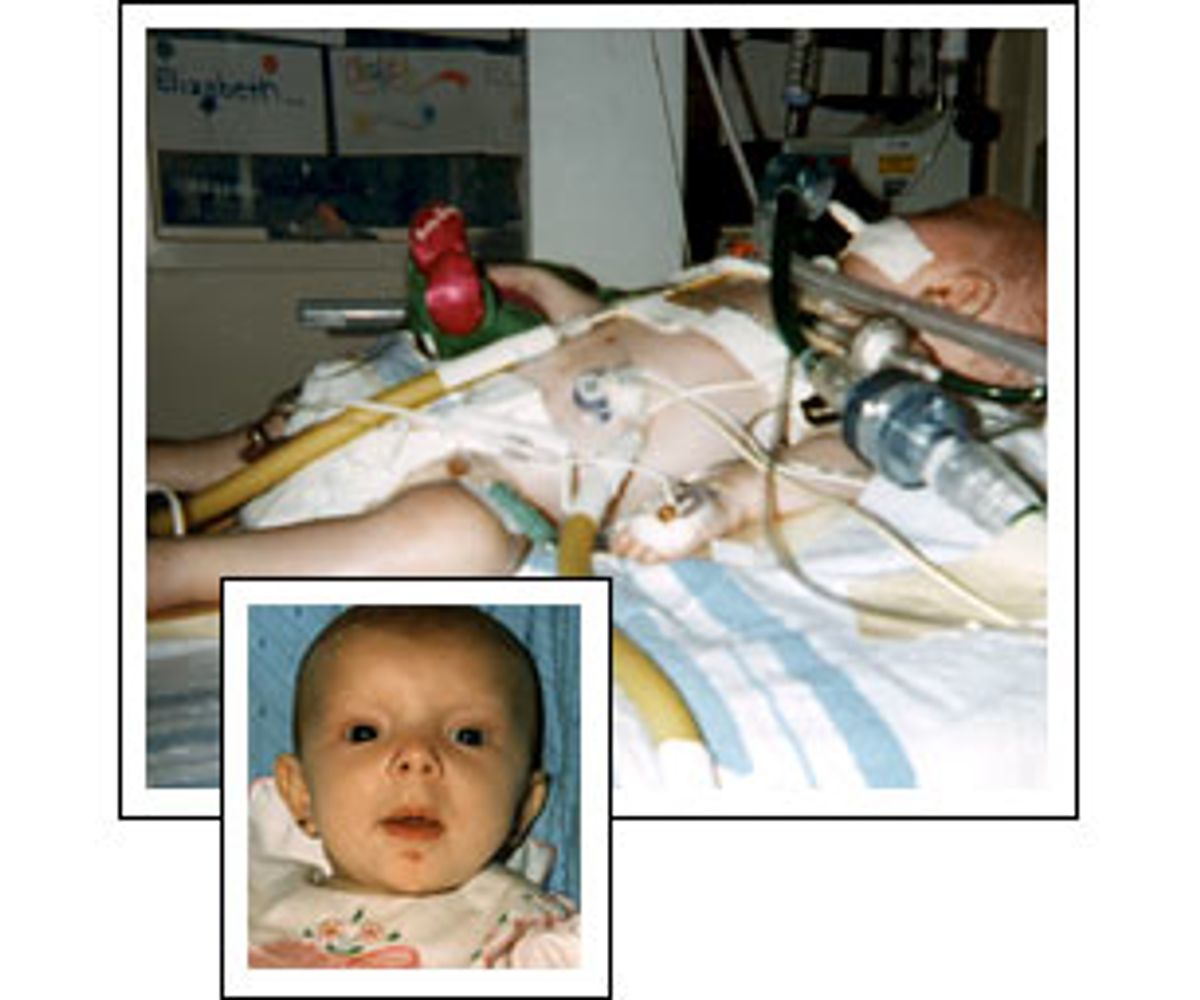

All of the pictures Glenn and Jamie Wooldridge have of their daughter, Elizabeth, are in one small photo album. It starts out, like most baby albums, with Jamie in the delivery room, proudly holding her new little girl; and continues with pictures of redheaded Elizabeth in her crib, playing with toys. But unlike most family photo collections, this one ends with just a few shots of the girl at 4 months old.

In these, Elizabeth is in a hospital bed, with tubes and machines connected to so many places on her 9-pound-11-ounce body that the weight of all the equipment looks like it could crush her frail chest and limbs. Stuck loose into the album is a newspaper clipping a paragraph or two long, celebrating Elizabeth's short life and announcing her death on Oct. 8, 1995.

Four years later, Glenn Wooldridge points to a stack of documents -- medical records, test results, doctors' referrals -- several inches thick, when he talks about what happened to her. Officially, she died of complications from cystic fibrosis, a devastating genetic disease currently affecting 30,000 adults and children in the United States. But her family, who lives in Rodeo, Calif., blames her death on their health maintenance organization's medical group. The Wooldridges say that the medical group should have authorized a "sweat" test that could have detected the disease when it was first suspected.

The sweat test was requested by her physician to rule out cystic fibrosis, but was repeatedly turned down by her HMO's medical group -- until Elizabeth's lungs collapsed a month before she died. "It was only a $125 test," says Glenn Wooldridge, an iron worker who looks older than his 29 years. "If she had gotten the test would she still be alive? She would have at least had a chance, they could have done something about the weight gain, they could have put her on certain medications ..."

It is still not clear that Elizabeth's life could have been saved if she

had had the sweat test earlier. But Dr. Nancy Lewis, a specialist in

cystic fibrosis and Elizabeth's pulmonologist at the time, believes that an

earlier diagnosis might have saved her life. "You have to realize that [in

the time it took for her to get the test authorized], she went from a baby

at home, to a baby in an

emergency room, to being admitted to the hospital, transferred to

the intensive care unit and going on life support," she says. "I think if

this baby had been diagnosed, she would have been managed differently, she

would have been kept off the ventilator with a diagnosis of

cystic fibrosis. When babies have cystic fibrosis, the ventilator pops

holes in their lungs, and they can't heal the holes in their lungs because

the ventilator keeps the holes going. In my experience, it's always a grim

outcome. I don't know if [Elizabeth] would have survived, but I would have

expected her to." And the Wooldridges want some type of recourse for what they believe were the penny-pinching policies that valued money over their daughter's health. But under federal law Glenn Wooldridge's ability to sue his insurance company is limited because he is a private employee. He can't sue for anything other than the cost of the care denied, which in this case is the cost of the test. Making things even more complicated for the Wooldridges is the fact that

the medical group is no longer in business and the HMO has merged with

another company.

"Anybody who wants to sue an HMO will tell you that it's not about the money, it's about proper care," Wooldridge says.

Horror stories like the Wooldridges' are well-known by now, and seem so horrendous that they almost sound the same, only with different names and different denied treatment options. There is the story of a child who had a brain tumor and was denied access to a specialist; the one about the person whose HMO only authorizes one colostomy bag per week, requiring her to clean it out after each use; and the one about the woman who needed a liver transplant and the HMO wouldn't pay for it.

"Every day doctors see evidence of delays or alterations in the health plan that they have for their patients; they are frustrated; they are exasperated with it," says Dr. Alan Baum, president of the Texas Medical Association.

It's no secret that spending on medical services is under much tighter supervision than ever before. With the old fee-for-service system, one health policy expert says, the problem was over-treatment. The problem now with HMOs is undertreatment, she says, and either can kill you. Inevitably, there are going to be cases where cost-cutting measures have unfortunate and even tragic consequences. But these stories are generally not representative of the everyday care provided by HMOs.

"It happens every day, but generally it's in subtle ways. Typically, it's not that someone has terrific chest pain and you think that this person needs an arteriogram and it's denied right on the face of it," says Baum. "It's more like well, maybe you need a consultant, or to try a change in medication, but that's expensive, so how about this other medication instead?"

The right to sue an HMO for emotional distress and punitive damages has suddenly become one of the hottest political and legal issues in the United States, at the state, federal and judicial levels. Last week, the House passed legislation -- the so-called Patients' Bill of Rights -- that among other things would give consumers that right. A similar bill passed by the Senate in July does not have the liability provision. The issue is now in the hands of a House-Senate conference, where the provision awaits its fate. Either way, both sides say, the state of health care in America will change drastically.

Proponents of HMO liability say it's the crux of any health-care reform, because it will actually change the behavior of managed-care plans. Out of fear, these people argue, HMOs will stop thinking about saving a few bucks for a treatment, because they could later be faced with millions in the form of a lawsuit.

"I think it's going to give patients the leverage they need to get more medically necessary treatment from HMOs that would otherwise be denied to save money," says Jamie Court, director of Consumers for Quality Care, a patients' rights advocacy group. "The point of this is to give patients a stick to use when they have to, but hopefully they won't have to. But the threat of it will make them be more reasonable with them and their doctors."

But will it?

"There's no evidence that HMOs or physicians threatened by lawsuits necessarily improve their behavior in the right way," says Walter Zelman, president of the California Association of Health Plans. "What doctors do, and HMOs are likely to do, is approve more procedures that maybe shouldn't be done and that only aggravates the problem."

What Zelman, representatives from other HMO associations and employers believe is that massive approvals of procedures will, of course, cost more money and that increase will be passed on to the consumer in the form of higher premiums. This, they say, will force even more people into the realm of the uninsured. According to a 1997 letter from the former head of the Congressional Budget Office, each 1-percent increase in the cost of premiums puts another 200,000 people on the street, insurance-wise. They also point out that a recent Census Bureau report says the number of uninsured in the United States is at the highest it has been in a decade.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Lawmakers say the answer to this dilemma lies deep in the heart of Texas. The Lone Star state is currently the issue's legal guinea pig. Two years ago, Texans became the first residents who could sue in state courts for denied treatment. Thus far there have been only five lawsuits. However, the Texas reform has a crucial element -- an external review process that both sides praise for resolving differences of opinion and keeping cases out of the courtroom. According to the Texas Department of Insurance, it has mediated 624 cases so far, deciding about half of them in favor of the patient and the other half for the HMO.

"I believe it has changed behavior. [The HMOs] are more consumer friendly and responsible to their patients," says Texas state Sen. David Sibley, a Republican and author of the bill. "Sometimes HMOs talk about the hidden costs -- what they mean is that they are giving patients what they should have gotten in the first place." Sibley adds that the review process, which patients have to go through before they can sue, has had a big impact on this. Texas also had massive tort reform in 1995, which among other things placed a cap on punitive damage awards, a factor Sibley, and a spokesman for Gov. George W. Bush's campaign, point to as the reason for its success thus far.

Texas is also an interesting case because of the largely bipartisan support HMO liability has garnered throughout the state, especially in comparison to the fractious partisan nature of the debate in the rest of the country. (At least up until last week's House vote, in which 68 Republicans broke ranks and voted for the HMO liability law, reform has been supported mainly by Democrats.) Sibley is a conservative, anti-abortion evangelical Christian, and a Bush ally. Although Bush vetoed earlier health-care legislation in Texas, he let this version become law without signing it.

Even today, Bush remains evasive on the issue. A spokesman for his campaign would not say which patients' rights legislation he supports, the one in the House or the Senate, but did offer this much: "He believes that people in federal plans should have protections similar to those in Texas. But he would not want anything passed in Washington to supersede the comprehensive reforms in Texas."

Just how the reforms are playing out in Texas is, ironically, not that different a story if you ask Dr. Dave Morehead, president of Scott and White insurance company, a small health plan in Texas. Yes, HMOs are changing their behavior, Morehead says, and Scott and White is an example of that. But the results are not a good thing, both for the company and the consumer. "What my medical directors tell me is they feel the weight of the excess liability to the point that they hesitate to make any kind of coverage decision for the health plan which carries any delay at all," he says. "If the doctor is not immediately available to discuss with them, or if for some reason it's difficult to get that information, [the medical directors] will very likely authorize the procedure because there is liability risk in delaying that decision."

What's happening now is over-treatment, he says, and every procedure carries its own risk. Scott and White now do not require authorization for tests like the MRI. He says that costs have gone up, and although he can't attribute it to the liability law, he believes it may have been a factor.

"Reasonable persons can be proponents of HMO liability and reasonable persons can be opponents, but neither of them can use the Texas experience as the basis of their conclusion. In Texas, the verdict is still out," says Jerry Patterson, executive director of the Texas Association of Health Plans. He implies that the number of lawsuits will rise: The Texas law was challenged in court, and upheld only in September 1998, which has prevented a lot of suits from going forward.

But Dr. Alan Baum, president of the Texas Medical Association, says HMOs are finally facing what doctors -- who can be sued for malpractice -- have faced all along. "I agree that doctors sometimes over-treat because of the litigious society that we are in. Doctors are always trying to make decisions: 'Do I need to order this test? Is it something that is truly indicated? I don't know if they need it but if I don't order it, I have exposed myself to litigation,'" Baum says. "But that has to do with if they are practicing in managed care or in private. Because of the environment that we're living in, we're all exposed to it. They are facing the same decisions that doctors not in that environment have had to face for years. Every day you have to make decisions that have potential liability for yourself or an HMO. If somebody makes a medical decision, our system says that someone should be accountable."

Dr. Paul Handel, a urologist in private practice in Houston, says anecdotally there has been a difference. "What I'm hearing from doctors is they have had fewer problems getting approvals and a big part of that is the ability to sue. But it also has to do with the establishment of the independent review; I think it's a godsend for the patient." He says it has been difficult treating patients in the state of today's managed care. He tells a joke one of his patients recently told him, which he thinks is indicative of a lot of people's disgust with managed care. "You know how an HMO is like a hospital gown?" he asks, and then pauses. "You only think you're covered."

He then recites some stories of how some of his and his colleagues' patients got stuck in HMO-authorization-denial hell. One person was diagnosed with cancer of the esophagus, and the HMO wouldn't let the surgeon operate on her for two and a half months -- all while the woman couldn't swallow and was in pain. Another patient who had prostate cancer was in the middle of radiation treatment when he changed plans. The new one required him to change hospitals, to one 150 miles away.

A plant in a clay angel pot sits on the dining-room table in the Wooldridge family's home about 25 miles northeast of San Francisco. Multicolored ceramic angels fill three shelves in the living room; and along the windowsill of the room of their eldest child, 7-year-old Aereanna, there are even more angels. Angels seem to guard almost every room in this white, blue-trimmed suburban home.

"After Elizabeth died, we told Aereanna that she would have a guardian angel watching over her; that's where all the angels come from," says Wooldridge. "We haven't kept anything from her, she knows that her sister had it and it caused her to die." Aereanna, a precocious second-grader, also has cystic fibrosis. (The couple also has another child, Zachary, who is 3 years old and recently had heart surgery.) And so, the Wooldridges' struggle with their HMO continues. They say that every month they have to wait to get Aereanna's prescription authorized. Just this past month, they say, it took a day and a half to get her pancreatic enzymes, which help her get nutrients from her food.

On the living-room floor is a machine a little larger than a computer printer, which was the source of a three-month struggle between the Wooldridges and their HMO's medical group. It connects two tubes to a small, black vest that clips around Aereanna's chest, and then vibrates, helping her to cough up the mucous that builds up in her lungs. She wears it for 10 minutes, twice a day.

In Aereanna's stack of medical papers, the saga is documented: There's the approval from the medical group for the $15,000 therapy vest, then a letter from it saying that it had approved the vest by mistake, that the couple's coverage did not include such equipment. Then comes a final note admitting that the medical group had been wrong, that the Wooldridges did have that coverage, and granting Aereanna her vest.

"I am tired of fighting with my HMO," Wooldridge says. "I don't feel that we should have to put this many hours in, to get what is basically ours, because I pay a premium."

Even Wooldridge will say that his family's experience with its HMO's medical group is somewhat of an anomaly; and although those in the managed-care industry acknowledge that the horror stories do occur, they say the frequency is greatly exaggerated. Compounding the problem is that unless it's taken to court or the patients waive their privacy disclaimers, HMOs can't legally tell their side of the story because of patient confidentiality laws. This may be part of the reason why Aereanna's medical group didn't return calls.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

In California, where the Wooldridges live, Gov. Gray Davis recently signed legislation allowing residents who work for private employers -- the majority of people in the state -- to sue their health plans for emotional and punitive damages. That legislation will not go into effect until January 2001, assuming it withstands legal challenges.

But public employees have had that right all along. The experience of the state employees, who belong to a plan called California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS), played a large role in getting the recent legislation passed, according to the bill's author, state Sen. Liz Figueroa, D-Fremont. There haven't been very many lawsuits, she says, and premiums have not risen very much as a result of them.

"The opponents say, 'Oh, it's going to increase the cost.'; 'Oh, a lot of people are going to become uninsured,'" she says. "Well, that's just not true. The evidence shows that it's not happening. The people who already have the right are just not doing it ... I don't believe that people will be sue-happy." The threat of suits alone, Figueroa says, will be a major factor in getting HMOs to change their behavior.

The folks at CalPERS say lawsuits have not been an economic disaster for them. "We have had relatively few lawsuits, not enough to be a major problem," says spokesman Bill Branch.

Like the Texas legislation, the new California law and both federal bills will require a review or arbitration process before most claims go to court. CalPERS has a variation on this as well. "We think one of the reasons [lawsuits have not been a problem] is that unlike [many] employers, we've long had an internal appeals process of our own. It is somewhat analogous to the independent review that is being widely proposed throughout the country."

According to a 1998 report by the accounting firm Coopers and Lybrand, for the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, there were 60 administrative appeals filed by CalPERS from 1991 to 1997 and only between 15 and 20 went to civil litigation. The report estimates that lawsuits increased premiums only between 3 and 13 cents per member per month. (CalPERS just raised its premiums by the largest amount in the past nine years. In the year 2000, they will increase by an average of 9.7 percent. The group says this increase is attributable to the rising costs of medicine such as prescription drugs.)

Not everyone sees things so rosily. "For them to claim that it's not affecting them is disingenuous," says Sen. Ray Haynes, R-Riverside. "What is affecting the cost of health care are these types of government mandates." He says that more than rising prescription costs might be playing a part in increased premiums. "What else is causing it to go up? Was it paying $120 million to a DA's [wife] -- was that one of the factors, could it have been?"

Haynes is referring to the $116 million January verdict against Aetna, brought on by the widow of a assistant district attorney who died from stomach cancer. The widow, Teresa Goodrich, claimed that for two and a half years before her husband's death, Aetna denied treatment. She sued for breach of contract and for shortening the life of her husband. The jury voted 10-2 in favor of Goodrich; it was the largest verdict ever against a health plan.

Haynes, like other critics, points to the human cost of increased premiums. "You are going to see millions of people lose their health insurance so a few can make a lot of money, and what is worse in the long run?" Haynes asks.

Before the Goodrich verdict, the largest in California, $89 million in damages, went to Nelene Fox's family in 1993. At 38, Fox, a Temecula, Calif., woman, was diagnosed with breast cancer. Her insurance company, Health Net, would not authorize the treatment -- a bone-marrow transplant -- because it considered it experimental. She decided to go outside the network and raise the $200,000 for the treatment herself. She died four months after finishing the procedure, and also, before the verdict came down.

"Probably the worst part of the whole thing for her was going into the street, and having bake sales to raise the money because none of us had the money; it was humiliating to make her whole life public," says her brother, attorney Mark Hiepler, who also represented her. "I can never prove that the delays and staying up 24 hours a day to raise the money [killed her]; I just proved that the denial was in bad faith. But it's the emotional stress someone goes through when they're fighting for their life and their health insurance. Many people have said that it's easier to fight cancer than their health insurance."

Subsequently, Hiepler has become one of the most prominent HMO liability lawyers in California. Despite these huge settlements, he doesn't believe that a wave of lawsuits will crash onto the HMO industry.

However, the low number of lawsuits in the past, both in California and in Texas, may not be indicative of the future, especially if federal legislation or the Supreme Court essentially dismantles an old federal law, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, known as ERISA, which has shielded HMOs from such lawsuits for the last 25 years. (The high court recently accepted a case, Pegram v. Herdrich, that delves into whether or not an HMO breached its duty to one of its patients. It will be looking at an appeals court's interpretation of one of ERISA's provisions, which requires HMOs to act as fiduciaries -- in other words, in the interest of their patients. In this case, Cynthia Herdrich of Illinois went to the doctor complaining of abdominal pain; the doctor, Lori Pegram, found it was inflamed but informed Herdrich that she would have to wait eight days for an ultrasound. Her appendix burst while she was waiting.)

Indeed, the legal climate is definitely changing -- some high-profile lawyers who have made their mark suing the tobacco industry are turning their attention toward HMOs. Just in the past week and a half, first steps have been taken to launch class-action suits against HMOs for not providing patients with health care. Two are against Aetna/US Healthcare and another one is against Humana Inc. Others are said to be in the works.

But not everybody thinks that any of this will help the situation, even if it does get HMOs to change their behavior marginally. "If you somehow put an HMO on the stand, everybody already hates them. They are like tobacco, and juries will hand out $100 million awards," says Dr. Robert Hertzka, an anesthesiologist in San Diego and a member of the board of trustees of the California Medical Association. But he says that HMOs will simply adapt. "They will just decrease their number of services or raise the premiums to employers. We don't think this concept of big-time lawsuits is a way to change behavior. The way to change behavior is to put decisions back into the hands of physicians."

Whatever comes to pass, Geraldine Dallek, project director for Georgetown University's Institute for Health Care Research and Policy, says it's important to keep perspective on the issue.

"We are not talking about the evil empire," Dallek says. "They have some things wrong with them, but they also have some things that improve care; it's a mixed bag. But consumers don't like someone telling them who they can or cannot see. Plans adopted policies with a sledgehammer, and made a lot of mistakes along the way. People became disenchanted. I really view these consumer protections as a way to rebuild trust and make managed care more consumer friendly."

None of the proposed legislation -- on the state or federal level -- is retroactive, so the Wooldridges could never sue for what happened in the past. Nevertheless, they say that they have learned to work the current system, by spending time scrutinizing all decisions regarding their children's health.

As for Aereanna, she is doing well; she's not taking as much medication anymore, has to put on her therapy vest only twice a day instead of three times, and hasn't been hospitalized for the last year. Overall, life for the Wooldridges has improved in recent months. But the HMO subject still gets under their skin. "Jamie spends so much time badgering them," Wooldridge says. "It is not cost-effective for them to keep denying us."

Shares