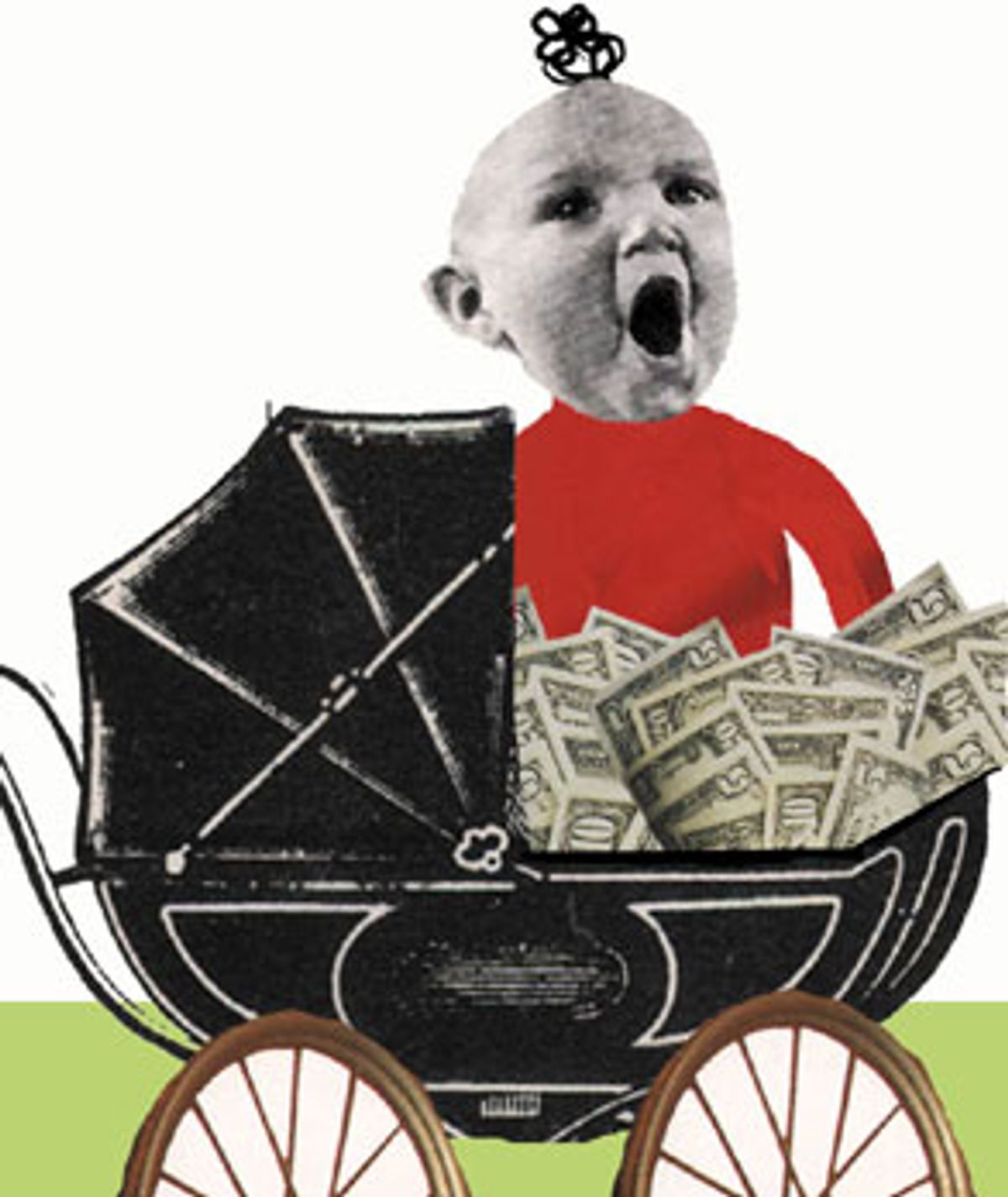

It started the day we brought our daughter home from the maternity ward. Or maybe it started earlier, the morning I saw that fateful blue mark on my wife's pregnancy test strip. No, it began before that. I started worrying about the cost of college tuition the night my wife and I first waded contraceptive-free into the sea of love, letting our reproductive juices mingle for a higher purpose.

Since then the question has dogged me -- relentlessly -- from every quarter. It's couched in TV ads, splashed on the sides of city buses and printed on brochures that arrive mysteriously in our mail.

A poster at my bank applies the pressure tactics to exceptionally ominous effect. An attractive four-color poster -- promoting the bank's financial planning services -- features a young, pigtailed girl working furiously at her homework, penciling out a tough math equation under the glare of her desk lamp. The ruthless caption bullies mercilessly: "She's doing her part ... Are you doing yours?"

Am I, in other words, as panicked as I should be about amassing a small fortune to pay for my kid's education? Well, yes; yes I am. My daughter is only 13 months old, and I can already feel the future's financial death grip clutching at my throat.

The numbers, as accountants are fond of saying, speak for themselves. Average college tuition has more than doubled in the past two decades, while median incomes for families with college-age children has risen only 22 percent, according to the College Board, the age-old juggernaut that administers the SAT.

And the National College Resource Association says we can expect tuition to continue to outpace earnings. According to the NCRA, the total cost of four years at both public and private colleges is expected, once again, to more than double over the next 18 years.

All these statistics tend to blur into a vaguely sinister mélange of facts and figures, so I decided to take a look at what the math means to my family. With one hand on the computer mouse and one hand clutching my heart, I used the tuition calculator on U.S. News and World Report's Web site to tally the cost of sending my daughter for four years, beginning 17 years from now, to the University of Virginia, a fine public school right here in my home state. My computation accounted for tuition and fees at in-state rates (assuming a tuition inflation rate of 6 percent), room and board, with some additional cash thrown in for books, supplies and personal expenses. The grand total? $127,446.

That's a fairly horrifying figure in its own right, but just for the sake of further self-torture I decided to ring up another estimate based on the prospect that my daughter -- who at 13 months is already exhibiting signs of cognitive wizardry -- will develop sufficient brainpower to get her into the Ivy League. What would it cost us to send her to, say, Harvard in 2017? $410,527.

The numbers are so humongous, I find myself staring at them glassy-eyed, dumbstruck by their sheer immensity -- like a solo climber standing at the foot of Everest contemplating its cloud-haloed peak. From my middle-income viewpoint, it's hard to know where to start saving to accumulate such a mountain of money. The numbers are unapproachable, intimidating, borderline crazy.

But it wasn't so long ago that the cost of college education was reasonable, even affordable. In-state tuition for one semester at the public university I attended in Virginia, in 1988, cost less than $1,000. I could write a check out of my humble savings account to cover the whole thing.

That's right -- I paid for most of my own college education, undergrad and grad, footing the bill with income from odd jobs and the usual streams of financial aid, which I'm still paying off. (Yes, Sallie Mae, the check is in the mail.) Back in my dormitory days I felt a little resentful of college roomies whose parents catered to their every financial whim, including the open-ended MasterCard account for beer and gas.

But I don't hold this against my parents now; on the contrary, paying my way through college furnished me with a go-getter's steady work ethic that I now see lacking in some of those old trust-funded college slackers, a few of whom still can't shake the notion that someone ought to be paying their way through life.

So, unlike some parents, I'm not adamant about bankrolling my kid through college. If she has to put in some hours at one of America's great retail chains to score some cash, or if she has to take on a little debt as she racks up her B.A., it'll do her good. When she forks over her own cash for tuition, she'll demand her money's worth every time she walks into a classroom. She'll pay attention; she'll learn more.

Still, I do the feel the instinctual pull to provide, and I want to do everything I can to lay the financial foundation for her education. So I did some research on the various savings plans. At first glance, the most appealing option seems to be the Uniform Gift to Minors Act -- called the Uniform Transfer to Minors Act in some states -- which would allow me to invest under my child's name while acting as custodian of the account. According to current IRS regulations, I can sock $10,000 tax-free per year into a UGMA account, and -- here's the bonus -- earnings on investments are taxed at the child's rate.

But there's one catch. If I invest in a UGMA account, every cent of the savings will become the sole property of my daughter the moment she turns 18. And if she decides to blow the cash on some badass SUV, or new breasts, or a yearlong outback jaunt with her heavily tattooed boyfriend, there's nothing I can do. Under UGMA rules, if I try to withhold the money, I've breached the trust terms and the kid can take legal action to get the cash.

So the question boils down to this: Do I trust that my darling 1-year-old will develop into a darling, motivated young adult who, placing a premium on the merits of higher education, will funnel her UGMA earnings straight into tuition? Or do I hedge my bets -- squirrel away the money in a nice, safe savings account that will really suck taxwise but over which I'll enjoy dictatorial control -- based on the prospect that she could turn into a wild-eyed hell-raiser?

In the end, like most financial investment questions, it's not a financial question at all -- it's a question of faith.

These days my daughter is just starting to learn to walk, striking out on her own first high-risk endeavor. With knees locked and arms outstretched she lumbers along like a mini-Frankenstein, and as I cruise along behind, my own arms outspread to shield her from hard surfaces and sharp corners, it's always a temptation to sweep her up and carry her on to wherever she's headed. It would save me some anxiety and save her some bumps and bruises.

But that would strip all the adventure out of it, too -- for her and for me. Half the fun of having a toddler, after all, is turning her loose on her wobbly legs and standing back to watch in wonder as a sudden, new grace begins to take hold of her, and she starts making her way steadily through the world, clearing all the obstacles I worried would knock her down, and I stand there, shaking my head, feeling silly for not giving her more credit.

Shares