I am enjoying the feeling of warmth and unaccountable optimism that can only come on a Indian summer afternoon. My daughters are happily picking the few confused daffodils that came out early in our Brooklyn garden. And then I open the newspaper.

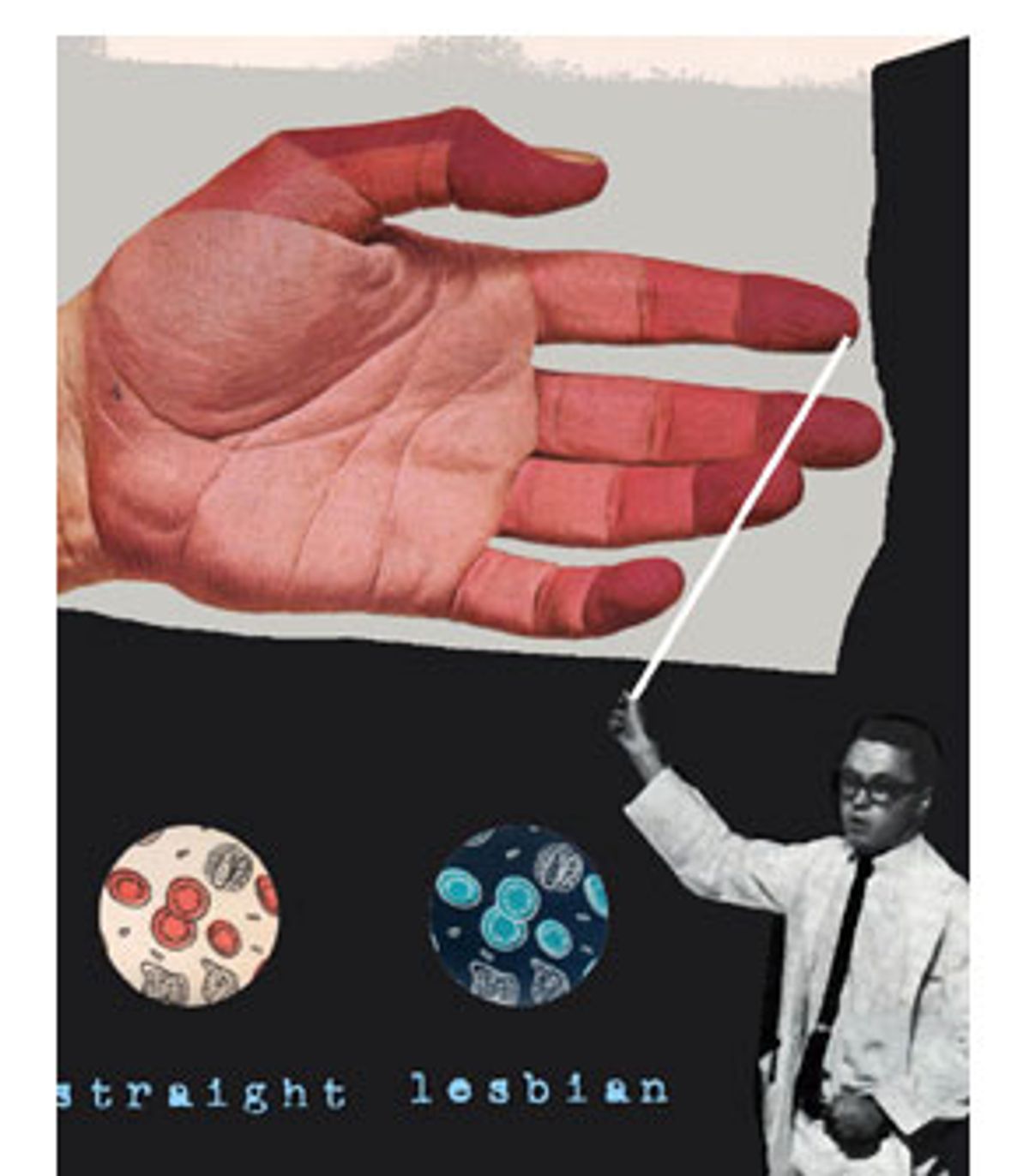

"Heterosexual Women Have Index and Middle Fingers of the Same Length, Lesbians Deviate From the Norm" is the first headline I see. I quickly glance at my fingers and feel a rush of relief. I have not been living a lie. My fingers conform to and confirm my true self. Then my relief turns to anger as I think about how one more shard of mean-spirited science has entered American culture as objective truth. And the truth of lesbian fingers is as sordid and as painful as any attempt to confine the imagination and creativity of human desire into a rigid and painful one-size-fits-all model.

The science of lesbian fingers is mean-spririted science for many reasons. First, this sort of study uses the existence of a statistical correlation to argue causation. Certain sorts of hands may be more likely to appear on the bodies of women who identify as lesbians, but isn't that a correlation as opposed to a cause? People with green eyes might be more likely to be accountants, but it is highly unlikely that there is a causal relationship between the two.

Second, the supposed cause of lesbian finger deviance is a "fetal androgen wash." In other words, lesbians undergo a wash of "male" hormones in the womb that gives them a "masculine" brain in a female body. In other words, the study wants me to assume that gender -- identified as masculine or feminine -- resides in the brain, even though there is no evidence of such a claim (or of an in-utero hormone bath, for that matter). In other words, I am supposed to believe that lesbians really are mannish and this is scientifically true.

Finally, the study believes that lesbians' mannish brains will naturally desire their opposite, which is to say, female bodies. Clearly a mannish brain could not be attracted to a mannish body any more than a girlish brain could be attracted to a girlish body because such attraction would be, oh lordy, same-sex attraction.

As I read the newspaper account of the "truth" of lesbianism, the balmy day begins to disappear behind dark, foreboding clouds. At first, I don't even notice the large raindrops as they fall silently onto the pages in front of me. All I can see are the words "lesbian fingers" and "science" blurring together into a single line. The sexuality line.

For over a century, Americans have been trying to establish the color line, to mark everyone as either black or white. These days the color line is supplemented by other lines, other worlds of either/or. We must be either male or female, straight or gay too. We cannot be both or neither or more than that.

At least with race we can now check more than one box, but of course we still have to check a box and ultimately it is still about being "white" or "not white" or "other." It does not seem coincidental that for every step we take toward erasing the color line and the gender line and the sexuality line in our private lives, there is a redoubled effort to draw these lines in the indelible ink of science.

Science -- racial science, gender science, sexual science -- has been the source of Truth not only for the modern age, but for our postmodern era as well. The only difference is that now we feed our science into our culture, into our newspapers and television shows and Web sites, at such high speeds that there's less and less time to think about its implications. There is no more public debate on the morality of drawing the sexuality line than there is on cloning or genetic engineering.

And in our hurry to draw the sexuality line, we have lost the truth of human bodies and desires. Humans are messy and our passions are even messier. Forcing our bodies to toe the line of binary ideologies only deadens us to the multiple possibilities that present themselves every time a child is born or an orgasm is had.

But I digress. It is raining. I have to rush my daughters inside. As we run, laughing and shouting, into our kitchen, they thrust the daffodils and dandelions they have plucked into my hands. For a moment the three of us are all holding hands, rain dripping down our faces, all talking at once about how beautiful the flowers are. Then I slip. I find myself checking the fingers of their right hands. At first I do this surreptitiously, but eventually I ask them to hold up their hands. I am relieved to see that their hands are, not surprisingly, like mine. I am also ashamed.

Why would I want something as rich and full as desire to be predetermined by their fingers? Whatever trajectories their desires take should be a surprise to me and to them. I want them to know desire as the accumulation of a lifetime of experiences, not the predetermined and rather boring creation of scientific sexism and heterosexism. I kiss both of my girls and tell them that I love the dandelions best. I figure it's never too early to introduce the wild and uncultivated nature of beauty to them. After all, finger size may not affect their future loves, but I will.

Shares