It's a humid Friday at the YMCA of the Rockies, and the afternoon activities at East Indian Heritage Camp are just getting underway. In a windowless conference room, a group of third-graders -- all adopted, all born in India -- are sitting on the floor watching a video called "Families in India" while chewing on pretzels. On the TV screen, a little Indian boy is explaining how his family makes dinner, as his mother sits on her haunches over an open fire and shapes naan bread with her hands. If the kids are aware that this is the modest life they might be living had circumstances been different -- if they hadn't been given up for adoption, if they had stayed in India -- their faces don't show it. They fidget and fiddle, paying very little attention to the domestic drama onscreen. In this group, self-awareness appears -- at least for the moment -- to be limited to immediate needs.

"We want more pretzels!" they cry out to their counselor.

Last year, 19,237 children were adopted from foreign countries and brought to the United States -- nearly triple the number of foreign adoptions just 10 years ago. Babies brought to the States from abroad -- many of them from Southeast Asia, Latin America, Russia and India -- now total nearly 15 percent of all adoptions in this country. Foreign adoption has become enough a part of American life to be the subject of at least one heartwarming advertisement for digital cameras (a couple in an airplane pose with their Asian baby). Tabloids and glossies regularly feature the stories of celebrities who have "imported" infants for adoption.

But as common as they have become, these adoptions are still controversial. The trend still rankles some Americans and raises questions for others, including those who study the growing phenomenon.

Why adopt foreign children when there are so many children awaiting adoption in the United States? Is it a good idea to take a child from her native country? Can an "ethnic" child be raised by white parents without becoming emotionally mired in issues related to their differences? How, for instance, does a white parent help a child of color deal with racism? These questions don't just come from those who observe the trend of foreign adoption with detached interest; they are typical of adopting families who find themselves raising kids from other countries in communities that are not prepared to deal with them -- the parents or the children.

So compelling -- and troubling -- are the issues related to foreign adoption, that an entire cottage industry has emerged to guide families through the process, providing advice during the adoption phase and help -- for parents and, eventually, the children -- thereafter. There are adoption therapists and genetic counselors who will "pre-screen" potential adoptees; there are local support groups for parents and kids; there is a flotilla of self-help books, Web sites and magazines; and there are companies that offer families guided trips back to the countries where their children were born.

Then there are the heritage camps.

Heritage camps are an early, and now pervasive, by-product of the international adoption phenomenon. Every summer, across the country, families with adopted kids converge on dozens of camps like Colorado's East Indian Heritage Camp, for an education in the culture, crafts and ceremonies of their "indigenous" countries. The Colorado Heritage Camp company alone offers camps for kids from Korea, Russia, the Philippines, Latin America, Vietnam, China and East India, as well as, incongruously, an African-American camp. In activity-filled weekend workshops, organizers say their goal is to give adopted kids a way to reclaim a lost, forgotten or maligned ethnic heritage, while providing a community of peers to get in touch with and discuss issues of racism and acceptance.

But the annual East Indian Heritage Camp weekend demonstrates a curious disconnect between the goals of its organizers and the needs of the campers. The pretzel-munching third-graders -- along with all the other kids, age 3 through 17 who arrive here with their parents -- come across as typical American kids whose "issues" have little to do with ethnic identity and more to do with predictable developmental hassles. The point of the camp is to deal with the kids' differences, to address issues of identity and assimilation. Yet, in a lot of cases, the kids seem to have coped with, or not yet encountered, those problems. The young ones want pretzels; the older ones want to go home, be with their friends and hone their coolness.

It is tempting to conclude that the camps, rather than resolving existing concerns, are addressing imaginary dilemmas dreamed up by concerned, culturally conscious adults. For the kids, the cultural education is cursory, at best; most seem to enjoy the weekend -- camp is camp, after all. Some experts argue that simply being around peers will have a positive long-term impact for adopted children, although no one has really proven that. Others warn that by emphasizing differences, the kids can become aware of, and be dogged by, concerns and fears that they didn't have before camp. But for the parents, the benefits are clear. Heritage weekends provide relief and support to parents with adopted kids who feel isolated and vulnerable in communities where their families are different; and worried about the impact of differences between them and their adopted children.

As Samir Tailor, a 34-year-old Indian camp counselor, puts it: "It's almost more about helping the parents than about helping the kids. Being from white America, they don't have to go through these [race] issues, but the tables are turned here. For the parents it's more educational, but for the kids it's more social."

Lunch on Saturday is a chunky Indian yoghurt soup, rice pilaf and spicey chutneys with turkey burgers; also on the menu is a meal of potato chips and hot dogs. The Indian children, almost without exception, head straight for the hot dogs. Their parents dutifully slurp the Indian soup.

"It smells funny," says one little girl, wrinkling her nose, as her mom encourages her to try the soup.

"It does smell funny," the mother agrees, but bravely downs a spoonful anyway.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The first heritage camp was reportedly founded in the late 1970s by Holt International, a foreign adoption service, at the request of adult adoptee clients who felt they would have benefited from some cultural education as children. But it wasn't until the 1990s, as foreign adoption exploded, that the heritage camp phenomenon really caught on.

Today, there are dozens of camps tailored for children from a number of countries, although a majority are for Asian or, specifically, Korean children (almost 10 percent of all foreign adoptees are from South Korea). Most camps, like Colorado Heritage Camps, are coordinated by groups of adoptive parents; others, like Holt Heritage Camps, are set up by adoption centers for the families that have used their services. Camps range from short day camps to weeklong sleepover camps; some invite the adopted children only, while others are for the entire family. The curriculum is typically the same for all the camps: a mix of ethnic crafts, dancing, sports, cooking, perhaps a dash of history or language, and a number of discussion groups where kids or parents talk about identity, heritage or adoption issues.

Colorado Heritage Camps, one of the most comprehensive heritage camp companies, runs eight camps every summer. Although the camp was initially founded 11 years ago by a group of parents of Korean children, Pam Sweetzer and her husband Dan -- themselves the adoptive parents of two children, from Korea and East India -- took over the organization nine years ago and have since expanded to cover an ever-growing range of ethnicities, from Russian to Chinese. Next year, they'll add a Cambodian camp to the list as a response to the requests of the parents who have attended (many of whom have multiple adopted children from different countries). "They just keep spawning these other camps!" laughs Pam Sweetzer, a friendly blond woman in her 40s.

Sweetzer runs the organization as a nonprofit, and the camps are heavily staffed by volunteers, who include adoptive parents, who help coordinate events, and local ethnic community members, who offer cultural expertise for the workshops and serve as camp counselors for the kids. Every summer, more than 900 adopted children and their parents participate in the camps, along with roughly 1,000 counselors and volunteers.

This year at East Indian Heritage Camp, for example, dozens of volunteers from the Denver-area Indian community have arrived to teach the kids yoga and Indian dancing, mehndi ceremonial tattoos, cricket, cooking, storytelling and Indian cinema. Parents attend cultural workshops like "Indian Caste System" and "Indian Wedding," as well as group roundtables discussing subjects ranging from attachment issues and adoption advice, to racism and identity issues. Some 165 children are attending this year; almost all of these children are adopted (a small number are their siblings).

East Indian Heritage Camp often seems like a lesson in multicultural political correctness. Parental enthusiasm for slurping Indian soup or learning about the caste system frequently outweighs the enthusiasm of the kids for the same things; perhaps because the parents are already biased toward a cultural education. "The families often wind up embracing the cultural activities more strongly than the kids do: often, they've made the decision to adopt from [a foreign country] because they are drawn to that culture, and they want to pass their enthusiasm on to their kids," says Dr. Dana Johnson, director of the International Adoption Clinic at the University of Minnesota. "But it's like anything that parents are enthusiastic about: Sometimes the kids embrace it as well, at other times it's like 'We have had enough of this stuff.'"

Running through the adult enthusiasm for all things foreign, however, is their concern that their kids might not think that being Indian is cool; that they'd be embarrassed about their place of birth or, worse, resentful. Since the parents themselves usually aren't Indian, they feel like the next-best place to teach those kids how to feel proud is at a heritage camp. ("Homeland tours," organized to take families with adopted families back to the country of birth, are another fast-growing response to this need.)

Gregory Keck, an adoption therapist and director of the Attachment and Bonding Center of Ohio, says that heritage camp can serve as "compensation" on the part of white parents who worry they've somehow done their kids wrong simply by adopting them. "There's this idea that we are taking kids away from their culture, and that you can do a number of things to help the child retain their culture, but I don't think you can," says Keck. "The fact is that when you leave a culture you are born into and come to America, you grow up as an American kid."

The parents, for their part, do seem to recognize that their kids are fully American (and Americanized); but they see the camp as an opportunity for their kids to be All-American and Indian -- superkids, essentially, schooled in two cultures. Nelly Gupta, a Westchester mother from Dobbs Ferry, N.Y., has come to East Indian Heritage Camp with her Indian-American husband Rishi and their adopted 8-year-old daughter Kiran. Gupta brought her child, she says, because she thought she was "old enough to understand" her heritage.

Gupta says she cried when her daughter carried an Indian flag up to the podium during the opening ceremonies. "I teared up that she might be able to claim, or reclaim, a piece of her identity and heritage," Gupta exclaims. "She's an all-American kid. But it's so important that kids from a third world country feel pride in their heritage -- it's not a Third World hellhole, but a culture that is rich and diverse in its own right. It's empowering."

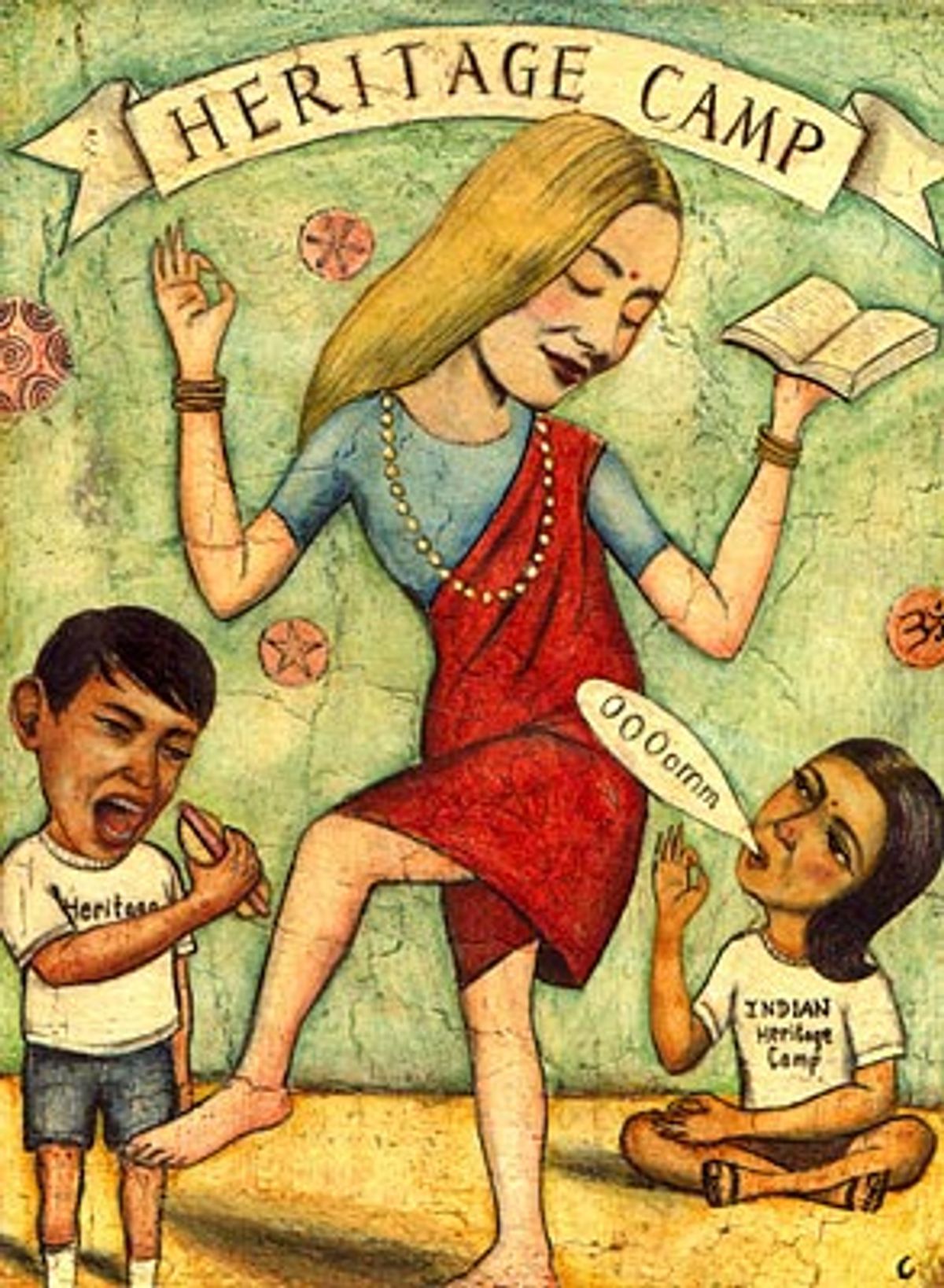

In the afternoon, a group of second-graders are getting a lesson in yoga from a pretty blond instructor, who reads them a story -- "How Ganesh Got his Elephant Head" -- before leading them through yoga exercises -- downward facing dog, standing tall trees. "Do you know what yoga is?" she asks them. "It's Indian," offers one little girl, helpfully. "It's a way to relax your body," says another.

The kids sit cross-legged, press their palms together and dutifully repeat the "ommm" of their teacher. "Feel the vibrations going through your body," she says with eyes closed and a placid smile on her face. The children obediently follow her directions, as she explains to them: "Yoga unites your mind and your body!"

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Heritage camps, as long as they take place in the U.S. and last for a week or a weekend, cannot provide an experience that could be called cultural immersion. At East Indian camp, kids rush from class to class every hour, getting brief instruction in a number of subjects that few of them will ever use at home. A child will learn a few yoga poses, but is unlikely to get a historical background of traditional Indian practice. And while the younger children seem to absorb some of the basic ideas -- it's Indian, it relaxes your body -- there is little guidance on what it all means.

This doesn't mean that the kids don't seem to enjoy what they are doing. The little kids especially tend to throw themselves into the crafts, dancing classes and games. One of the most popular events of the weekend for the small children is what is billed as the Holi Festival; in India, this is the "festival of colors" which welcomes the spring, during which celebrants fling colored powder and water on each other as a celebration of life's "brightness." At East Indian Heritage Camp, the kids are simply ushered to a soccer field, where they are handed squirt bottles filled with tempera paint and encouraged to make a total mess.

No one has bothered to tell them what the festival symbolizes -- it's too hard to coordinate, I'm told, since the kids often arrive at the field at different times -- but the kids don't really seem to care. They simply grab the squirt bottles and go wild, until everyone on the field is screaming with laughter and covered from head to sneakered foot in brilliant blobs of paint.

The teens, however, are a different story. Many have been attending for years (a majority of camp attendees are repeat visits). And although they are given the most lenience in their schedules, and attend advanced classes with more cultural context -- Indian cooking, cricket, music lessons, history discussions -- they can be indifferent, if not resentful, about the whole package.

One afternoon, in a stuffy cabin far from the central gymnasium, teens are being taught how to make rose punch and raita, a dish of cucumbers and yogurt. Some girls cluster around the teacher, Purnima Voria, a dimpled woman in a sari and bindi who talks a little like Martha Stewart with an accent. "Cooking is an art," she says, carefully arranging peppers on the top of the dish. "Don't be afraid to take it a little further." The teenage boys slump in chairs as far away from the table as possible, with the exception of a few boys who seem to be mostly enjoying their close proximity to the girls.

The real activity is outside the cabin, where a group of girls in tight jeans and belly-baring tops -- they've chosen not to don the required camp T-shirt -- sit and flirt with boys in skate shorts and basketball jerseys. Jared Juy, a kinetic 14-year-old who does proudly wear his camp T-shirt, shows an ebullient enthusiasm for the camp in general; but he doesn't seem to care much for the cultural classes. Mostly the camp is a way to meet girls. "I've gone every year since this camp started. It's great, I get to see all my friends, and girls," he says, as he wraps his arms around a pretty friend. "The best thing here is freedom from your parents."

His companion, 16-year-old first-time attendee Tasha Condie from Utah, is less overtly enthusiastic about the weekend; her parents have brought her here at a friend's recommendation, and although she says she's having an "OK time," she would rather socialize than learn how to cook or play cricket. "We need to party," she explains, "... and they need to bring a TV."

"They'll show movies later," Jared points out.

Tasha rolls her eyes: "Yeah, Indian movies, to be exact."

At one point, toward the end of the weekend, one of the volunteer camp coordinators has clearly reached her limit with the teens' apparent boredom. She pulls the teens into a room and begs them to tell her what they would want to do in future years. More culture classes? Language classes? Nothing at all?

One girl suggests Hindi classes; another wants to learn ancient Indian history. But most teens simply nod in agreement with the sentiments of one boy who blurts out: "Let us choose what we want to do, and let us just hang out if we don't want to do anything."

Heritage camps are caught in a bind: What they really need to teach is not what it is to be Indian, but what it is to be Indian-American, which can be different for each child, depending on countless factors. The hope is that the kids will go home armed with cultural knowledge that they'll use to shape their own Indian-American identities. As Susan Soon-keum Cox, vice president of public policy for Holt International heritage camps, posits, "It helps them to understand where they fit in the world: Are they Korean-American or American-Korean? Which goes first? They need to be able to find that balance ... go away proud of the fact that they are part of two cultures and identities."

Identity, however, isn't acquired through cooking classes alone. So while the culture classes -- the sports, the dancing, the games and crafts -- are a colorful lure that brings families to Colorado, it's the discussion groups and socializing with peers that are ultimately the focus of the weekend. Essentially, it's a support group, candy-coated with Indian cooking and ethnic crafts.

Admits Pam Sweetzer: "The culture stuff is mostly a reason to get them here to meet each other."

Sweetzer, like a lot of the parents here, is most concerned with making sure that adopted kids "fit in" in the world. And the parents have reason to be concerned: Most families at East Indian Camp seem to come from small, Midwestern communities where there are very few Indian families (or any minorities, for that matter), much less families with white parents and Indian children. They worry, understandably, that their kids will grow up feeling alienated or rejected by white kids, and possibly misunderstood by adults, including their parents.

"For parents who adopt foreign children, it's a two-way street: You get tsk-tsk faces from older white women, but also all the people of color come up and tell you what a beautiful baby you have," says Dr. Johnson. "We live in a racist society, and when we think of what our children will face none of us want our kids to face things that will be hurtful; every parent of a child of color is going to be concerned about racial bias. It doesn't happen very often, so it's not that pervasive, but those people do exist in society, and nothing is ever going to take that away."

At East Indian Heritage camp, it's normal to have an ethnically mixed family; it's normal to have dark skin. Wanda and Peter Bonnel, a friendly couple from Topeka, Kansas, have been coming to East Indian Heritage Camp for eight years. Their children -- a daughter, age 13, and a son, 15 -- were both adopted from India. "Only three families in Topeka have adopted Indian kids, so our kids know they are different," says Peter Bonnel, as he and his wife sit outside sipping beers on Friday night. The kids are roasting marshmallows; the whole family has just attended a concert of classical Indian sitar music. "This camp allows them to be a majority instead of a minority."

"This is the only place in the world where we are considered a normal family," agrees his wife, Wanda. "We keep coming to camp to show them it's OK, there are other families like this. It gets harder [for them to be Indian] the older they get, because they just want to fit in."

Dr. Johnson points out that it's important for kids who are adopted from foreign countries to spend time with others of the same ethnicity as they are growing up. Even if they "feel" white and are accepted within their community, at some point -- usually once they leave their families for college -- they will realize that are identified as "different" from white kids by virtue of their skin color; at the same time, they may not be accepted by other people of color, either, because they are too "white."

"Kids need to get together with other kids that look like them and respect that, so that when they look in the mirror and see someone from Korea or China or India they think that's OK," Johnson says. "The more they can get together with other kids who look like them and have had that experience, the better off they are."

The kids at East Indian Heritage Camp seem to support Johnson's thesis; most express a quiet comfort at simply being around other kids who look like them, even if they aren't eloquently expressive about the race issues at hand. As Tasha Condie puts it, "I feel really comfortable. It's cool being around all these other Indian kids who are adopted." Or Chandre Murrell, age 12: "In my school there's only one other person who is Indian. So coming here is fun." Her friend, Alysia Larson: "I don't feel different here; I'm just like everyone else."

Nineteen-year-old Jancy Turner, a camp counselor who was, until recently, an attendee, says that when she began coming to camp as a 14-year-old, meeting all the other Indian kids was like an epiphany. "Where I grew up, I was the only person with dark skin. I never knew any Indian families, and I didn't know anyone who looked like me. And then I came here, and everyone looked like me," she says. "I felt so accepted and right at home -- I didn't have to worry what people thought."

The parents, struggling with their own issues -- chief among them, unfamiliarity with racism -- sit in roundtable discussions and worry about how to deal with potential harassment. In one roundtable, parents peppered a group of young Indian men about how their kids would be treated in school. The panelists warned parents that their kids would probably face epithets like "Sand-nigger" or "Camel-jockey." The parents, in turn, betrayed a feeling of futility as they quizzed the panelists about ways to help their kids cope with such epithets.

"I didn't necessarily do [my kids] any favors by pulling them out of their culture, bringing them into mine, and expecting them to be peachy keen," says Sweetzer. "I can listen and understand and feel sad, angry [when they have hard times with other kids], but I can't really relate to being a minority; I don't know what they go through. And like anything your kid goes through, you can't fix it all and you feel helpless."

At this level, the camps often feel like a place to exorcise white guilt. Parents are aware that their kids might face racism and won't really be able to fall back on their families for help. The parents, convinced they won't be able to relate to the pain of prejudice, want at least to expose kids to their heritage as a way to bolster pride and give them strength in their daily trials.

This is the primary goal of one of Colorado Heritage Camp's more controversial workshops -- African-American camp, for white families that have adopted black kids. Unlike the other camps, this one doesn't really teach much about Africa, since most of the kids were adopted from agencies in American inner cities. Instead, the camp teaches African-American history -- soul food cooking, civil rights history, freedom songs -- in the hopes of giving black kids and their parents an education in race and the social injustices that children of color in America have endured over time.

Discussions about racism often take place, at least at the Colorado Heritage Camps, in "HeART Talks" designed for individual age groups. Kids take part in roundtable discussions in which they are encouraged to bring up skin color and feelings of difference. The talks are closed to reporters, but camp coordinators say that they can be emotionally cathartic for the participants. Twenty-one-year-old counselor Priya Kumar recalls a teenage girl from a previous year who refused to wear the camp T-shirt or participate in activities. She wore heavy pancake makeup and eye shadow. When she was encouraged to open up in one of the HeART Talks, says Kumar, the girl broke down and said that she had been beaten at school because she wasn't white: She wore the makeup to hide the bruises.

But not all the kids at camp want to belabor the ways that they feel different; in fact, some kids seem to feel like the camp is forcing race issues down their throat. Abby, a fourth-grader who says she likes coming to camp because she gets to "make friends," was quite clear about her least favorite part of the weekend: The HeART talks. "Last year some mean woman asked me if I felt dumb because I had brown skin," she complains. "It hurt my feelings."

There's a danger, says therapist Keck, that a kid dragged to a heritage camp and forced to talk about ethnicity will just feel more alienated. By reinforcing differences, kids are made more aware of them. "If the kids don't want to go, but people say they need to go because they're adopted and Korean or Indian, most of those kids will wonder they can't just grow up and go to soccer camp," says Keck. "These kids do have issues with race, but I often think that [with adults] the race issue takes on a life of its own that is sometimes larger than it needs to be."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

It's difficult to determine exactly how heritage camps affect an adopted child's sense of self and identity, because there are so many different iterations on display. There are little kids who can't wait to put on their Indian dresses for the final night's "Spice of Life" dance festival; who prattle on about all things Indian and say they love to come every year. There also are kids who refuse to wear Indian clothes; who sulk on the edge of classes instead of participating; or who are far more interested in flirting with boys than talking about their countries of origin.

"In the world of adoption there are kids who are completely attracted to heritage camps, and others who have no interest -- just as I didn't have much interest in going to my own family's reunions," points out Keck. "People have to be careful not to think that heritage camps do more than they do. Unfortunately it's gotten a bit trendy to have an adopted child and want to send them off to camp, even if they don't want to go."

Furthermore, Keck points out that there are many phases in an adopted child's emotional development -- particularly when it comes to skin color and ethnicity. Some younger children, he says, often just want to identify with their white parents, and he has heard stories of kids who sat in their bathrooms trying to "scrub the dark away to become lighter." But, he says, "most kids end up knowing they are a different race; and then in adolescence there is a new resurgence in identity-seeking." Other kids, he says, will grow up without ever displaying interest in their heritage or skin color.

One visible benefit of East Indian Heritage Camp is that many of the younger children seem to have soaked up some idea that that it is OK to be Indian, that they don't need to scrub their skin color away. If anything, they've gone to the other extreme: "You talk to the little ones, and ask them where they are from, and they say India, not Colorado," says Kumar. "They know they are special. They have a sense of heritage, and where they come from."

The hope of parents is that once the kids happily accept their Indian heritage, life might get easier. Karen Baughn of Glendale, Arizona, the mother of 16-year-old Komal (as well as six other adopted children, from a variety of countries), says confidently that heritage camps have helped her daughter's self-esteem about being Indian. "Since we started coming to camp, being Indian doesn't bother her anymore," says Baughn. "She hasn't had any identity issues, she fits right in, even though she's the only East Indian at her high school."

But despite her mother's assertions, it's clear why Komal fits in so well at school: She's a beautiful teenage girl, trendy and cool in her crop-tops and jeans. When Wanda Bonnel shares a story about how her daughter went through an "Indian phase" in fourth grade, wearing Indian clothes to school every day, Baughn looks up in shock. "My daughter wouldn't be caught dead in Indian clothes," she says. "She wants to look just like everyone else."

And that, of course, is the crux of the issue at heritage camp. The kids, raised like typical American kids, want to fit in with other kids at their schools. But fitting in sometimes has less to do with skin color and more to do with simply being just like everyone else in your class: dressing right, looking pretty, saying the right things, listening to the right music. And while there are certainly kids at camp who will have serious identity issues or problems with racism, and whom these heritage camps could help, many of the older kids like Komal seem already to have done a fine job of assimilating despite their parents' concerns.

After all, the hope of "fitting in" and "being just like everyone else" is exactly what parents can never truly promise, regardless of whether their kids are adopted. Sure, bringing kids to heritage camp could bolster their confidence, give them new avenues of self-exploration and a better awareness of what their skin color means; it also clearly reassures parents that they've used every resource available to families in their situation.

As Dr. Johnson puts it, "I can't really think of a downside of a culture camp." But whether three days at a heritage camp can change the quality of the other 362 days of the year is impossible to know.

Shares