In the early evening of May 18, 40-year-old Fizoon Ashraf was cooking steaks in the small kitchen of her Brooklyn home when there was a knock at the front door. Her two youngest children -- Safraz, age 7, and Shavana, 10, jumped up from the TV to answer it while she continued draining vegetables over the sink.

They returned to the kitchen, confused. "Mom," Shavana said, "two strangers dressed in uniforms like Rasheed are at the door."

That was all Fizoon needed to hear to know something very bad had happened to her son, 22-year-old Rasheed Sahib. Fizoon's eldest, and a specialist with the Army's 4th Infantry Division, Rasheed had shipped out to Iraq on April 1. Fizoon had been deeply against his going; she worried constantly about his safety and about his being so far away from his family. Two days before he left, she had demanded, "How will I know if something bad happens to you?"

Relying on the good nature and patience that had earned him the nickname "Smiley" from his friends, Rasheed had tried to comfort his mother. "Everything's already taken care of, Mom," he'd said. "People will get to you if I have an accident. Two soldiers will come to the door and they'll have a sheet of paper that will explain what's happened to me."

Fizoon had ordered Rasheed to be quiet. She didn't want to hear words bringing her worst imaginable fear to life. A little over six weeks later, the knock came anyway. Without thinking, she screamed at her children for answering the door and allowing a tragedy to enter their home. Her entire body shaking, feet suddenly heavy, Fizoon struggled to walk the few steps to the front of the house. There the soldiers were, just as Rasheed had described.

"No," she told them, her voice trembling. "You are not bringing a message about my son."

They began to apologize, explaining there had been an accident. That's all Fizoon heard before fainting to the floor.

"I used to say, when I heard that soldiers passed away, 'How do [their families] go on and live?'" Fizoon says. "Now, it's happened to me, and I don't know what to do. Every day, I cry for my son. I know God will hate me for this, but God is unfair."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Since President Bush declared the end of major hostilities in Iraq on May 1, 149 American troops have been killed, 68 from hostile fire, and 81 from non-hostile circumstances such as accidents, illness, etc. But Rasheed Sahib's death is something of an anomaly. He was fatally shot in the chest by another soldier in the unit who was cleaning his gun. While a criminal investigation by senior Army officials is still underway, the Department of Defense has so far declared the incident an accident. Rasheed's family isn't convinced. They worry the Army is withholding the truth from them and that perhaps Rasheed was even targeted because he was a Muslim.

"My son is being treated like no one," Fizoon says now, her voice breaking. "But he is someone to me. There have been hundreds of deaths and the government says it will help families, but no one is trying to help us. Bring the truth to me! That's the least you can do for me!"

Rasheed's family -- his mother, stepfather, two sisters and brother -- all live in an immaculate two-story row home on a quiet street near the border of Brooklyn and Queens, N.Y. Their small home is well-tended, a bouquet of silk flowers adorning a table in the narrow hallway that stretches from the foyer back to the kitchen.

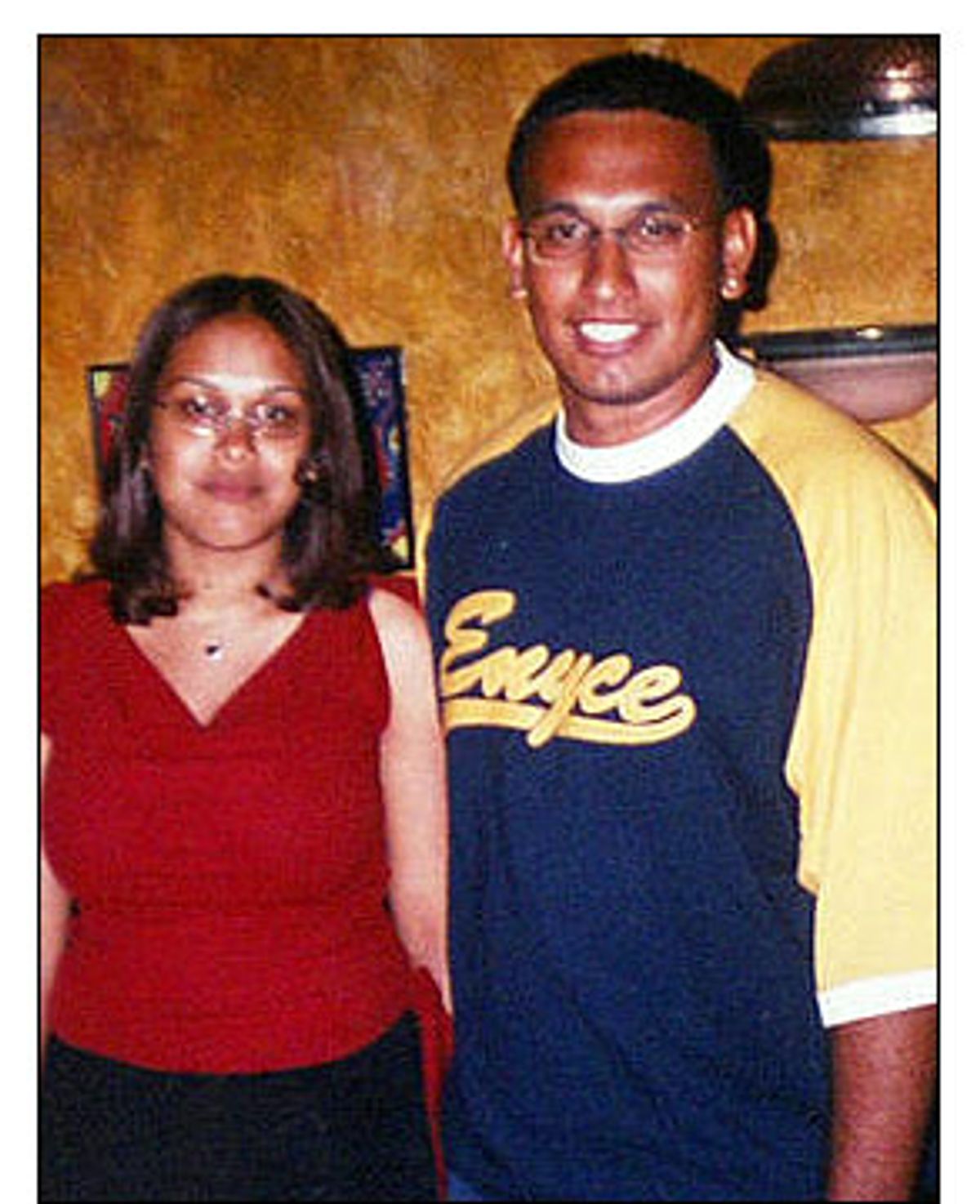

The living room, painted the color of yellow lemonade, is filled with enough seating -- two couches, a table and chairs -- to comfortably sit the members of Rasheed's extended family who showed up on a recent weekday evening to discuss his sudden and bizarre death. His grandmother, Jainab Ashraf, sits quietly on a chair, arms folded in her lap, her lips drawn into a tight line. Two of Rasheed's aunts, Nazeea, 21, and Fareena, 27, could easily be mistaken for fashion models; they have long dark hair and penetrating eyes, and they are dressed in hip-hugger jeans. Rasheed's youngest sister, Shavana, and 7-year-old brother, Safraz, alternate between watching TV in the other room and returning to study the faces of their relatives, not entirely sure what's going on. With her coffee-colored skin, wire-rimmed glasses and ready smile, Rasheed's 20-year-old sister, Nafeeza, resembles her brother the most.

The grief of Rasheed's mother, Fizoon, is most palpable. Although a photo of her, taken at a family party last year, shows a smiling woman with a bright expression, enormous black circles now ring her eyes. At times, she stares off in space, as if wishing herself somewhere else. She cries when she speaks of her son -- many times referring to him in the present tense. Halfway through the interview, she curls into a fetal position on the couch, seemingly oblivious to anyone else in the room.

"I miss my son so much. I have no one to walk through my door now," she says. "May 18, he died. That was after the war was over! He was just standing there, doing his work, and someone shot him. I have no life no more. He was my life."

Rasheed was born in Guyana in 1982. His family's life there was difficult: His father harvested sugar cane, and money was scarce. When Rasheed was just 2 years old, his father was killed in a hit-and-run car accident. It was a tragedy that would eventually shape Rasheed's own life.

"Ever since he was little and his father passed away, Rasheed wanted to be a cop to help catch bad people, like the one who killed his father," Fizoon says. "That was his goal. To help people. To be there for them."

Fizoon remarried Seenarine Jonathan three years later, and the family moved to America in 1989 -- in part to be closer to their relatives, but also to get a fresh start. Rasheed was just 7 years old when he arrived in New York and instantly loved everything about it: the Yankees, WWF wrestling, action movies. He loved to rap and taught himself how to draw his own comic strips.

As he grew older, Rasheed developed a fondness for souping up cars, teaching himself not only how to repair them, but also how to install the best stereos and wheel rims he could afford. And he loved barbecuing.

"Last summer, during a huge downpour, Rasheed even went outside with an umbrella to barbecue steaks," his sister Nafeeza says. "He always tried to make the best out of any situation."

"He never stopped smiling," is how 19-year-old Louie Permaul remembers him. As kids, the two became instant best friends when Rasheed offered Louie half an ice cream sandwich he'd just bought at the store. "He didn't even know me," Louie remembers. "But that was just Rasheed. Always helping people out, keeping everything together."

Rasheed was fastidious, carefully organizing everything he owned. When his mother advised him to file away important receipts or papers he might need in the future, he took her counsel to heart and began saving every receipt he was ever given -- even from Kentucky Fried Chicken. Once Rasheed began working at Dunkin' Donuts during high school, he made sure to have his uniform dry-cleaned every week.

His aunt Fareena laughs. "I said, 'You only make $100 a week and you spend money on dry-cleaning?' But he wouldn't just iron his uniform. He said the cleaners did a better job."

Rasheed was close to his sisters and aunts, although they teased him mercilessly -- joking that his name sounded like a girl's and he might as well be called "Rasheeda," or that his ears stuck out like a bat's.

"He never tried to defend himself," says Fareena. "He didn't care. He'd just smile and be like, 'Whatever.'"

Rasheed's bond with his mother was especially tight. From an early age, he helped her cook, clean and take care of his younger brother and sisters. But because he knew how much Fizoon worried about his well-being, Rasheed never asked her advice about enlisting in the Army. He had dreams of one day becoming an FBI agent and felt the military would provide a solid way in. He also knew Fizoon would be against his going away for long periods of time and into potentially dangerous situations. So, secretly, he signed up for the Army in the fall of 2000, after he turned 18. Not until two days before he left for boot camp at Fort Bragg, N.C., did he finally tell his mother.

"I wasn't angry," Fizoon says. "Just scared. He had so many other options, so many other things he could have done ... But he looked so happy when he came back [after boot camp], that I wasn't scared. I wasn't worried for him no more."

"The Army made him more of a man," agrees Fareena. "He was still a kid when he left, but I didn't know him when he came back. He was over 6 feet tall! So strong, and he looked so handsome. "

Rasheed loved being in the military, but it wasn't always easy for him. During a training incident in spring 2001, he was accidentally shot in the leg and had to spend time in the hospital. After 9/11, he confided in Louie that other soldiers in his unit (then at Fort Hood, Texas) admitted they felt like jumping him simply because he was Muslim. Although he was not a devout practitioner of Islam who prayed five times a day, his mother believes Rasheed found time to pray each night before bed and read the Quran.

"He sounded scared on the phone when he told me about [the soldiers threatening him]," Louie says. "[When Rasheed joined the Army] nobody had fears about him being Muslim. He was an American soldier. But you never know about ignorant people."

Knowing that these incidents would make his mother frantic with worry, Rasheed never said a word to her about them.

"He never told anyone if he had a problem," Nazeea says. "He would just try to find his own solution."

Although Rasheed was due to be discharged from the Army in February, he was happy enough with his position to reenlist for one more year. When his unit, the 20th Field Artillery, shipped out to Iraq in the spring, he assured his relatives he wouldn't be anywhere near the line of fire. He'd be safe, he said, distributing weapons to soldiers just outside of Kuwait. Only after his death did they learn he was in the midst of major combat action just north of Baghdad. In a letter to Louie, postmarked May 9 but not received until two weeks after his funeral, Rasheed confides he's with a group of 11 other soldiers who've nicknamed themselves "the Dirty Dozen." Their goal: tracking down Iraqi war criminals and ex-leaders, who many times used the women and children in their villages as human shields. "We're doing 'Black Hawk Down' stuff, but without the helicopters," he writes. He remarks he's lost close to 20 pounds, and says the bugs in the desert are eating him alive. "There are even dead bodies in the same building we're sleeping in now," he writes, although not specifying if they are Iraqi or American. He implores Louie to send him letters, photos and Sean Paul reggae CDs, and to ask his family to do the same. "I need shit like that to keep my sanity," he writes.

His sister, Nafeeza, can barely conceive of her brother in such gruesome circumstances. "Once, Rasheed cut his finger on a laundry line pulley while he was hanging up clothes," she remembers. "He saw a little blood and he got all dizzy ... Even getting a mosquito bite, he'd feel hurt. I'd see the news during the war and think, 'Thank God Rasheed isn't on the battlefield.' But he really was."

Still, no one doubts that Rasheed was proud to be serving the country of which he had only recently become a citizen. "He didn't regret being over there," says Fareena. "He wrote that he felt so good when people came up and thanked him. He saw so many devastating things that Saddam Hussein had done, so many starving children, and in the end, he was glad to be there."

"I didn't ever watch the news," Fizoon says." I didn't want to know what condition he was in. Did he have enough food? Enough water? I don't want to be happy if he's not happy."

Rasheed never called after he shipped out in April, although his mother waited constantly by the phone to hear his voice. On May 18, less than half an hour before two soldiers appeared at her door, she had even picked up a photo of her son and said aloud, "Rasheed, I'm still waiting for you to call me."

At that point, he couldn't. According to the Pentagon, one of Rasheed's fellow soldiers (whose name has not yet been released to the public, or to Rasheed's family) was cleaning a gun that accidentally discharged. The bullet entered Rasheed's chest and killed him, although it has yet to be revealed if he died immediately.

Rasheed's body was sent home five days after his death. Although Muslim tradition dictates a ceremonial washing of the body before burial, his was in such an extreme state of decay that the director of the funeral home decided excessive handling would be unsafe.

"He was hard to look at," says Nazeea. "He wasn't the Rasheed we know."

"I keep thinking, 'Maybe that's not my son. Maybe they made a mistake,'" says Fizoon. "That's what I was hoping."

Six days after his death, Rasheed was buried with full military honors at Rose Hill Cemetery in Linden, N.J. More than 100 family members and friends showed up to pay their respects to Smiley one last time. A voluminous program was hurriedly put together, with those closest to Rasheed reading him heartfelt goodbye letters, and even poems. "Those were all good times that we all shared," wrote Louie's 24-year-old sister, Priya. "I just wish that you were spared/ But don't worry baby boy, your crew will soon be there/ So we can continue with our barbecue in the rain."

On the back cover are the solemn signatures of his friends, like a yearbook Rasheed will never get the chance to read.

After the initial news of a tragedy, many families of fallen soldiers carry through the bittersweet process of gaining some closure -- learning more details of their child's death, receiving letters of condolence from other soldiers in the unit, taking stock of their beloved's possessions. But Rasheed's family has remained stuck in the uncertainty of that very first day, over three months ago, when Army officials first arrived on their doorstep. There has been no autopsy report given to them, although an autopsy on Rasheed was supposedly done. Only days ago did Fizoon finally receive a death certificate -- but a Xerox copy, not an original. While Rasheed's military uniforms have been mailed to the house, his $300 watch is still missing, as are the gold stars and crescent medallion he constantly wore around his neck. Even his car -- a beloved, souped-up 1994 Honda Civic that he left behind at Fort Hood -- has not been located or returned to the family.

"[Army officials] keep saying, 'It takes time, it takes time. You're not the only one who had someone killed,' Fareena says. "But Rasheed was doing the same thing as the other soldiers over in Iraq. He should be treated with respect. He was there to help everyone ... The military claimed one shot and he died, and it takes over three months to do an autopsy report?"

"We just want some answers. Some closure," interrupts Nazeea. "Every day seems like another year to us."

According to Marc Raimondi, spokesman for the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Division, Rasheed's death is part of an ongoing investigation. "We have a lot of pieces of the puzzle together, but not all, although I fully anticipate we will," he says. "We have a very, very good idea of what happened and who is involved."

Asked if Rasheed may have been targeted because he was Muslim, or whether his death may not have been accidental, Raimondi declines to speculate. "At this point in time, we have no reason to believe it was anything but a tragic occurrence, but there won't be any questions left unasked by our agents. I understand the family's desire to have every bit of information they can. They deserve no less. And I can assure them that we are doing everything in our power to get them the answers they want."

Raimondi said he did not know when the investigation would be complete.

Rasheed's family has no option but to wait. Meanwhile, the grief they feel has infiltrated each of their lives.

Since Rasheed's death, Fizoon has been too emotionally distraught to return to her job as a home healthcare attendant. Although her doctor has prescribed antidepressants and anti-anxiety medication, she's not sure she'll be able to continue them, since her prolonged leave of absence has caused her family's health insurance to be suspended. Instead of applying to colleges, Nafeeza has taken a job at a local hardware store so she can help her mother care for her younger brother and sister. Her distress over Rasheed's death has manifested itself as a bleeding ulcer; twice, she's had to be rushed to the hospital. Even Safraz has become suddenly aware of the concept of dying, asking his mother, "Mom, how old is Rasheed? Why did he get killed so young? Don't you have to be old and sick to die?"

"He's still waiting for his brother to come home," Fizoon says. "He wants me to keep Rasheed's clothes so he can wear them when he turns 22."

Fizoon's voice dissolves into sobs. "First his father, now Rasheed. This one, I can't steady myself. He took my whole life away. 'I'm going to be taking care of you, Mom,' he said. 'Everything's going to be OK.' That's what I'm living with: When? When will it be OK? My house was full of joy when my son was here. Now, it's full of sadness."

Shares