A small group of anti-abortion advocates were gathered around the entrance to the National Geographic Society in Washington on Saturday, April 24, at 4 p.m., protesting a cocktail reception being thrown by the National Organization for Women, the Feminist Majority and Ms. Magazine in preparation for the next day's March for Women's Lives rally. The protesters held pictures of mangled fetuses; a young woman with a bullhorn shouted, "Abortion causes breast cancer! Cervical cancer! Liver cancer!" I was almost inside the building, accompanied by attorney and head of the Los Angeles chapter of NOW Shelly Mandell, when the voice grew sharper.

"Gloria! Gloria!" yelled the woman through the bullhorn. Gloria Steinem, the feminist, writer and founder of Ms. magazine, was gliding up the stairs behind me. Dressed in fitted black pants and a top, her colorless hair long and recently washed, a brown leather knapsack thrown over her shoulders, and her big trademark brown-tinted sunglasses, the impossibly slim Steinem looked like she had stepped directly out of 1978. Mandell and other organizers greeted her warmly and were ushering her into the party when a young Asian woman, who looked to be in her early 20s, stopped still on the way down the hall. "Are you -- are you Gloria Steinem?" she stuttered. When Steinem, who last month turned 70, answered in the affirmative and shook her hand, the woman simply held it, shocked. "Oh! Oh my god! I love you!" she said.

It was a moment that very much captured the spirit of this weekend in Washington. Part reunion tour, part celebrity-sighting smorgasbord, part multigenerational get-to-know-you session, the march and its party-studded lead-up were filled with equal parts blank looks and rapturous handshakes, as the women's movement -- all three or four or five generations of it -- gathered en masse for the first time since 1992 to rally for the protection of women's health and reproductive rights. And as the march sponsors grappled for attention and mingled as longtime sisters-in-arms, there was a lot of staring going on: 30-year-olds and 40-year-olds and teenagers and feminist heroes and grandmothers and children all gaping at each other, wondering if they had enough in common to reinvigorate a movement that has lain fallow for over a decade.

The March for Women's Lives was organized by seven sponsors: the Feminist Majority, the National Organization for Women, NARAL Pro-Choice America, Planned Parenthood, the Black Women's Health Imperative, the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health, and the American Civil Liberties Union. It was impossible to charter a bus on the East Coast because so many were booked to come to D.C., Mandell told me. Now that it looked as if the event was going to draw hundreds of thousands, the organizations that had planned it were jockeying for the attentions of the press and of the handful of luminaries descending on Washington. In addition to the National Geographic reception, Saturday saw a Moby concert, high tea with California Sen. Barbara Boxer, featuring Steinem and a performance by Carole King, a party at California Sen. Dianne Feinstein's home, a kickoff rally for volunteers at the Armory, and a private dinner with Steinem.

"I think the [multi-organization] planning has been constant compromise," said Mandell, who said she had known most of her fellow planners for more than 20 years, "but not open warfare." At the National Geographic Society, as a single-file line of women in their 30s formed to shake hands and have their pictures taken with Steinem, "Jaws" actress and Feminist Majority board member Lorraine Gary sat with her husband, former Universal Studios head Sid Scheinberg. "It's a reunion, and a handing off of sorts, to young women and women of color," she said. Gary, who had greeted friends as she walked into the party by announcing that she'd had "the pleasure of walking out on [NARAL president] Kate Michelman earlier today," explained: "There's always tension [between organizations] when there's branding involved." The march was not officially branded by any of the sponsors, but groups were wrestling for visibility: Upon arrival in the city, every sentient being was fitted for a T-shirt, hat and sign emblazoned with the logo of whichever nonprofit organization spotted her first.

On the other side of the room, Ms. magazine editor Elaine Lafferty was experiencing faux-exasperation about another kind of branding. "Greta vandalized my car!" said Lafferty in mock distress. She was referring to her friend Greta Van Susteren, the Fox News anchor. Van Susteren had placed a Fox News bumper sticker on Lafferty's car before Lafferty arrived; it wasn't exactly de rigueur ornamentation among the feminists. Lafferty was wearing a pink version of a popular shirt featuring a chiaroscurro image of Hillary Rodham Clinton on the front. The day before the demonstration, it was still unclear whether the New York senator would be making an appearance during the weekend. "Round and round she goes, where she stops, nobody knows," said Lafferty.

Steinem, who had removed her medium heels to get closer to the microphone, was addressing the party. "Tomorrow is going to be a life-changing event for all of us, but also as a country," she said. "Who knows what's going to happen in the next two days, but it's going to be exciting." About a third of the hands shot up in response to Steinem's question about how many were at their first march. "So that means we've got the hardcore and we've got the young ... Onward!" she crowed, before turning the podium over to other speakers, including actresses Kathy Najimy, Camryn Manheim and Tyne Daly, Sen. Boxer, and Feminist Majority president Eleanor Smeal.

Daly, the star of "Judging Amy," who made her name on "Cagney and Lacey" -- possibly the best television show about women ever -- is silver-haired, and had dyed the ends of her coiffure a shocking pink, in honor of the march's "raspberry" color scheme. Her fingernails and toenails were polished to match. After her speech, Daly retreated to a quiet corner and talked about media priorities. "People didn't seem to care about the death of soldiers or the ruination of the economy, just about Miss Jackson's breast," she said, suggesting that "we as women should go to Washington to march and collectively bare our breasts" -- and here she grabbed her own ample rack -- "These are the WMDs: the Weapons of Media Distraction." Daly, a mother of children ranging from 36 to 18, said she knew that she, however well respected, was not likely to be the lightning-rod personality that electrified the nation's youth. "I wanted the cast of 'Sex and the City,' I wanted the cast of 'Friends,'" she said of her Hollywood organizing for the march. "But we live in an atmosphere of fear. It's hard to get people out."

Jennie Eskin, a 19-year-old Princeton student there with her mother, Santa Barbara state Assembly member Hannah-Beth Jackson, said that among her college friends, there isn't a high rate of activism. "I think we're more complacent about it, we just accept [reproductive choice] as our right," she said, adding that most of her friends wouldn't know Steinem if they fell over her. "They'd know the name, maybe," she said, "but not really who she is." Eskin and her friend Chase Taylor, a 19-year-old Hofstra student, said that they would love to see more celebrities with whom they identified up at the podium. "Brad Pitt! Good lord!" said Eskin, adding, "It's not going to be the older women who fought the battle who are going to inspire us. It's people we recognize and quote-unquote admire."

Later that night at the Armory, NOW president Kim Gandy boasted that a third of the next day's anticipated demonstrators were coming from college campuses. And Feminist Majority president Eleanor Smeal told the crowd, "We're going to outnumber the right wing! Doesn't that sound beautiful?" The enthusiastic response to Smeal was nothing compared to the hoots of support that followed California Rep. Maxine Waters' suggestion that George W. Bush "go straight to hell!" (Unfortunately, Waters' comments were followed by a folky performance of "Every Sperm Does Not Deserve a Name.")

On the Metro after the Armory party, a young man with low-slung jeans and a sparkly lion face painted onto his neck fingered a button on his female companion's jacket. "What does 'no coat hanger' mean?" he asked. "That's how women used to get abortions," replied the young woman.

"No way!" said the young man. "That's awful! I mean, I like the button, but that's awful!"

The girl looked shocked. "Haven't you ever seen 'Dirty Dancing?'" she asked.

By 9:30 on Sunday, Steinem was already at the march, in a brown leather jacket, being bombarded by fans and the press. Just four months away from the December death of her husband of four years, David Bale, Steinem had been pulled in many different directions throughout the weekend. With professional and historical links to both Planned Parenthood and the Feminist Majority, who have absorbed Steinem-founded institutions Voters for Choice and Ms., respectively, the iconic feminist seemed the ideal dish served at every March for Women's Lives dinner, cocktail reception, panel discussion or breakfast meeting. "To a certain crowd, she personifies the women's movement," said Lafferty.

That morning at the march, the focus of feminist idolatry was broadening. "Oh my god, it's Betty Friedan," said a voice behind me, as organizers swarmed the 83-year-old author of "The Feminine Mystique," who had arrived by golf cart. But Friedan was soon eclipsed by news from the street. "Hillary is sitting in a car around the corner," said an organizer, puffing slightly. As if on cue, a recording of Fleetwood Mac's "Don't Stop Thinking About Tomorrow" blared from the speakers, bringing a tear to the eye of anyone who ever entertained the notion that Bill Clinton was really going to change the world. The teenage radical cheerleaders performing across from the press tent looked unmoved by the tune.

Soon Sen. Clinton was on the stage, drawing a booming cheer from the crowd. "Twelve years ago we had a march," began Clinton. "And we elected a pro-choice president. This year we have to do the very same thing." The crowd shouted, "Hill-a-ry! Hill-a-ry!"

Susan Sarandon, in an eye-popping multicolored striped jacket, was getting pushed and pulled in and out of the VIP area, as organizers tried to figure out how to get everyone in line to march. "This is happening today because we're threatened for the first time in 12 years," said Sarandon, as an eager volunteer placed a NARAL sign in her hand. Sarandon's 19-year-old daughter was not with her, but the actress said that she thinks the women's movement already resounds in teenage heads. "Not only is this my daughter's first opportunity to vote, but she's also at an age where her reproductive freedoms are most important to her," she said. "So maybe Social Security issues don't speak to her. But the right to safe healthcare for herself and all the world is something to pay attention to." Sarandon was bumped slightly from behind by a throng of security people ushering former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright into the VIP area.

Near the street, Elaine Lafferty was visiting with Lassie, the Ms. magazine Chihuahua, as a passerby said into a cellphone: "I am looking at Port-o-Sans, some chick playing a guitar, and Madeleine Albright." Cybill Shepherd paced behind the stage, clutching her 16-year-old daughter Ariel's hand with one hand, and a heavily annotated speech in the other, mouthing the words to herself. It was tough to hear Shepherd's speech from behind the stage, but it sounded like the first few sentences, which drew a huge response from the crowd, involved the word "pecker-heads."

While Shepherd was speaking, organizers corralled the "special guests" into marching formation. "I think the celebrities should be in front," said businessman Ted Turner, as Tyne Daly, Sharon Gless, Ashley Judd, Kathleen Turner, Frances Fisher, "Thelma & Louise" screenwriter Callie Khouri, Amy Brenneman and Camryn Manheim were pushed into a rough front line. Lorraine Cole, the leader of the Black Women's Health Initiative, pointed out, "This is historic because it's the first march in which organizations for women of color are official planners." Over at the staging area, '60s folk singer Holly Near was playing.

The celebrity front line lurched forward. Ashley Judd, in a T-shirt reading "This Is What a Feminist Looks Like," began to bellow, "We won't -- go back! We will -- fight back!" At Constitution Avenue and 15th Street, the group was forced to mate with a rogue collection of celebrity speakers who had gotten a late start: Shepherd, former "Saturday Night Live" star Ana Gasteyer, and former "Wonder Woman" Lynda Carter, whose presence, along with that of Gless, Daly and "One Day at a Time" star Bonnie Franklin, ensured that the march provided a nearly complete set of prime-time stars. From 1980.

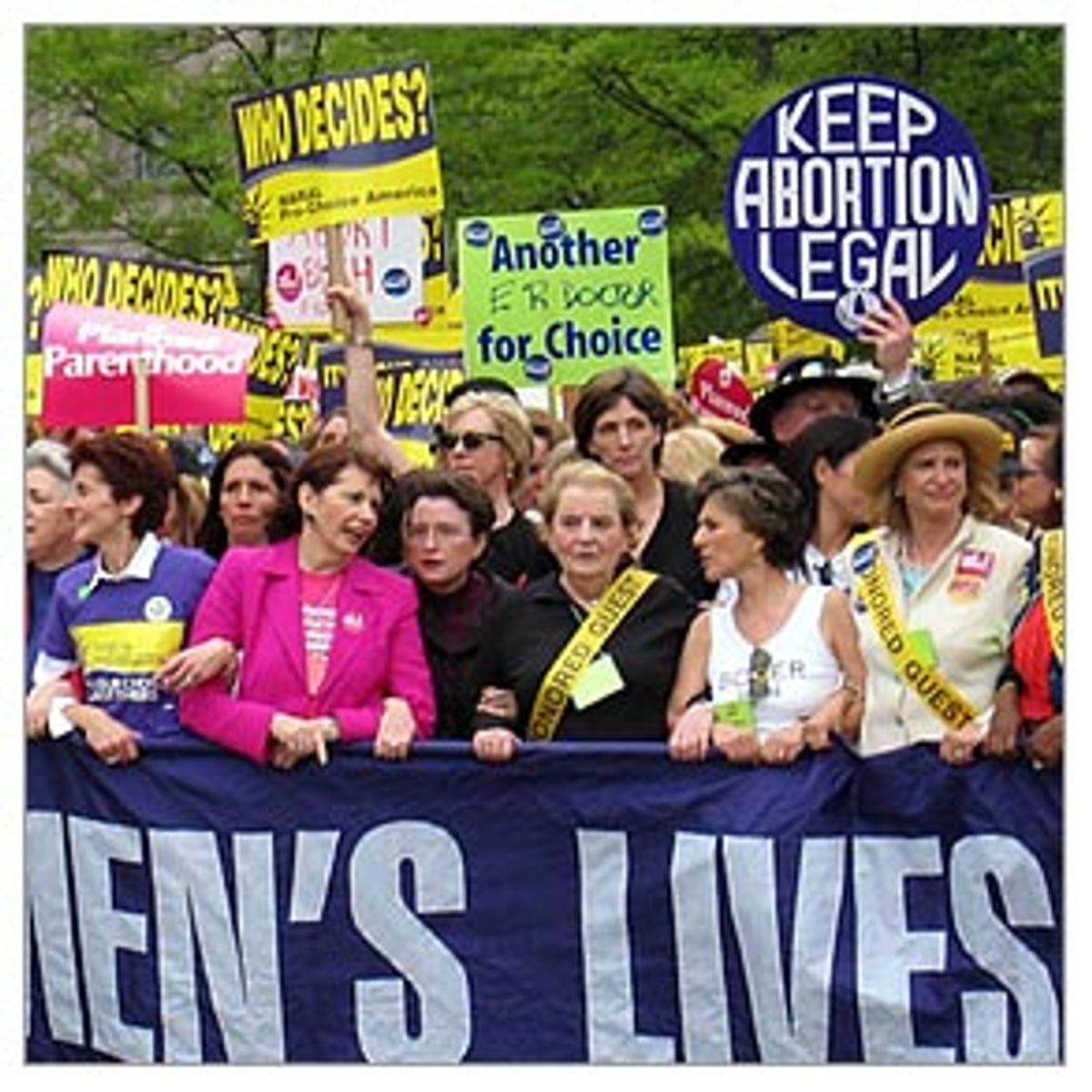

As organizers, led by legendary march-coordinator Alice Cohan, barked orders like "Step back! No! Forward! Move it out! Come in!" Steinem stood serene, holding up the middle of the purple March for Women's Lives banner. After an over-enthusiastic handshake of my own, I asked her how this march was different from all other marches. "This is much more crucial," she said, glancing over her shoulder at the forming line, "and much bigger and much more diverse." She was still saying something -- about the Bush administration's commonalities with the Vatican and extreme Muslim governments -- when I was jostled backward by a wave of unsteady celebrities, still trying to merge. "We don't have room to move back!" Judd explained to the coordinators, earning the gratitude of the squashed marchers behind her.

After a lot of tugging and swaying, the Hollywood celebrities forged ahead, and I found myself arm-in-arm with several dozen "peacekeepers," a bubble of bodies protecting the second front line of organizers and politicians including Smeal, Gandy, Cole, Planned Parenthood president Gloria Feldt, Albright, Pelosi and United Farm Workers of America founder Dolores Huerta. After over an hour of stop-and-go marching, through media and protesters with more bloody-fetus posters and rosaries, we pulled back toward the Mall, where someone had decided to play decidedly youth-inappropriate music like Vanilla Ice and Billy Joel. Breaking out of formation and striding toward the afternoon stage, Madeleine Albright said, "I marched in 1989, and this is much bigger. I have just been told that this is the biggest march in American history."

As the Indigo Girls took the stage, the study in paleo-feminism reached my own generation. From Betty Friedan to Holly Near to Lynda Carter to my college memories of angry white chicks with guitars, almost every antiquated layer of the women's movement of the past five decades had been unearthed and introduced onstage on Sunday -- except, of course, for the cultural signifiers for the generation behind me.

Organizers had been right: The young people had come. The streets were thronged with high-school and college students, men and women. They had cheered and giggled and marched. But it felt like a young crowd attending a party thrown by an old organization. How could 18-year-olds, no matter how eager they were to sign up, get onboard with '60s folk singers and Whoopi Goldberg, who had taken the stage with a coat hanger and said in an almost accusatory voice, "You understand me, women under 30? This is what we used!" It was an attempt to connect, but it came out sounding like she was scolding a generation for its privilege.

But haven't we been making the point for years that reproductive freedom wasn't a privilege? That it was a right that these kids should be able to take for granted? Isn't that exactly what Whoopi Goldberg and Gloria Steinem and Holly Near and Tyne Daly had hoped and fought for for so long? So the question was: Where were the people who could speak to this generation that has grown up not knowing what a coat hanger has to do with feminism from their own perspective? Where were Mary Kate and Ashley Olsen? Where was Britney? Hell, 10 years older than they, I have no idea who might be able to lead them. But I know that I didn't see her at the march.

And where were John Kerry or his wife, Teresa? It seemed like bad form not to have shown up. Especially when Howard Dean, in a spiffy dark suit with a red beetle-tie, was kibitzing backstage. "This is exactly the energy we had on our campaign," said Dean. "You just need someone to strike a match under it, and that's what I did."

Onstage, Gloria Steinem was speaking, and she was finally talking -- for real -- about the young women in the crowd. Repeating the statistic that one-third of the demonstrators were under 25, Steinem said, "Let's never again hear about how there are no young activists. It's just that some of us older folks don't recognize the form in which they protest. We thought we had to cover up our bodies. They are saying rightly that they want to be nude and safe ... They don't all sound like issues of the past and they shouldn't."

It was the march's first moment of real reach beyond the age barrier, or at least an acknowledgement that there were communication challenges between grandmotherly activists and their daughters and granddaughters. But did Steinem have any choice? She was there for my mother; she was there for me. But I doubt that any daughter of mine will know who she is. Who will be there for her? It's been 12 years since the last march. Twelve years from now, Steinem will be 82 years old. Who will take her place onstage? Who else will combine good politics and good brains and good looks in a way that makes young women stop dead in their tracks to shake her hand? It must have been scary, to look over three quarters of a million people, and realize that she doesn't have anyone to hand a torch to.

"Before I leave you all," she said, "let me hear you say it! 'Do we have the power?' Let me hear you say it: 'We have the power! We have the power!'"

Shares