Day after day, Army Spc. Cheyenne Forsythe roamed around Saddam Hussein's magnificent palace compound in Tikrit listening to dazed and tearful soldiers, many of them barely out of high school. With its lush palm gardens and ornate frescos, the palace was an incongruous place to be counseling American troops shaken by the harrowing montage of combat. There were dazed young men whose skulls had been grazed by 9 mm rounds. Tearful soldiers who had seen their buddies' bloody limbs blown off by roadside bombs. Thousand-mile-stare soldiers whose convoys had been ambushed by invisible combatants firing rocket-propelled grenades. Soldiers like Staff Sgt. Georg-Andreas Pogany, who came to see Forsythe after being deployed "about two inches from hell" near the town of Samarra, deep in the insurgent-infested Sunni Triangle.

Forsythe, a member of the Combat Stress Control Team in the 85th Medical Detachment, pulled up a couple of plastic chairs on the edge of a marble veranda and listened to Pogany's story, taking notes in what he calls his "little green book." It was Oct. 2, 2003. Forsythe had never met Pogany and has not seen him since. Here are some of the things that Pogany said, according to Forsythe's notes:

"Fell apart."

"Shaking, throwing up."

"I don't want to fucking die here, man."

Over the next few hours, as shadows stretched across the Tigris River and the oppressive heat abated, Forsythe heard Pogany recite the classic signs of combat fatigue: loss of appetite, sleeplessness, hyper-vigilance, a quick-trigger startle reflex, an inability to focus. Dozens of soldiers had told eerily similar stories to Forsythe about how Iraq had gotten under their skin. How they were locking and loading at the sound of their own Hummer door closing, how they found themselves flipping out all the time, tossing their food, cradling semiautomatic weapons like teddy bears, sweating, hyperventilating. Paranoid. Worried that they were letting their units down. Worried that they'd never feel normal again.

As they talked, Pogany worried aloud about his wife back home, that he hadn't cashed his military travel voucher, that he didn't understand what the hell was happening to him. He wondered why he started shaking and vomiting uncontrollably after seeing what was left of an Iraqi who had caught a Bradley's 25 mm round in his torso.

Pogany recounted that after he saw the body, he had a smoke and went to bed, but woke up 20 minutes later and dashed to the latrine to vomit. He shook all night, didn't sleep, hallucinated that the roof was coming down on him. In the morning, he knew something was wrong. He went to his Special Forces team sergeant. Pogany, who was not a Green Beret but a military intelligence soldier who had been assigned to work for the elite 10th Special Forces Group unit as an interrogator, knew he was viewed as an outsider by the Special Forces team. The team sergeant (due to Army regulations, Pogany cannot reveal the name of any person in his unit) was clearly unsympathetic to the new guy's complaint. He told Pogany to pull himself together, gave him two Ambien, a prescription sleep aid, and ordered him to sleep.

Later that day, Pogany was still shaky and told the team sergeant he needed help. The sergeant called him a coward and threatened to cite him for violating some provision of the military justice code. Eventually, Pogany was taken to the Tikrit compound and saw a chaplain, who recommended a chat with a Combat Stress Control Team member.

Forsythe listened as the sky grew dark and reassured Pogany that what he was experiencing was absolutely normal. Pogany cried several times.

No worries, Forsythe told him. It would be OK. It happens all the time.

Forsythe talked Pogany through a few stress-reduction techniques. Deep breathing. Thinking about things he liked to do. Listening to music. Calling his wife. Reading a book. They were both from Florida, and Forsythe said the inspector general on the compound was a Dolphins fan. They could maybe watch a game together. They talked for a few hours.

According to Pogany, the talk with Forsythe helped. Pogany said he felt better and was looking forward to getting treatment and going back to duty.

Forsythe made a recommendation to the Army psychologist, Capt. Marc Houck -- a textbook call for the type of combat stress Pogany was suffering from, taken from the "Leaders' Manual for Combat Stress Control," Army Field Manual 22-51. Forsythe recommended that Pogany spend a few days with a "Restoration Team" at the nearby Tikrit airfield to learn coping skills and stress-reduction techniques. In all likelihood, the training would give Pogany the help he needed to return to his unit. "The doc agreed it was a clear-cut case," recalls Forsythe.

Pogany says he repeatedly told his chain of command that he wanted to stay on in Iraq, and says this contention was confirmed by a sworn statement by a Military Intelligence chief warrant officer. Houck's Report of Mental Status Evaluation, dated Oct. 2, 2003, stated that Pogany "reported signs and symptoms consistent with those of a normal combat stress reaction." Houck stated that "short-term rest, stress coping skills, and/or brief removal from more dangerous situations are often adequate to resolve such reactions." He agreed with Forsythe's recommendations that Pogany spend time with the Restoration Team and concluded that Pogany "is cleared for action deemed appropriate by command."

What the command deemed appropriate surprised Forsythe. From the start, he could tell that Pogany's Special Forces superior officers weren't buying any combat-stress crap from this Army soldier. Forsythe witnessed the company sergeant major berating Pogany within earshot of a bunch of other soldiers. "The sergeant major really had a hard-on for this guy [Pogany]," recalls Forsythe, 28, who left the Army in March when his enlistment period was up and now lives in Killeen, Texas. "I'm like, 'Wow, what did he do to get this guy on him like that?'"

The next day, Forsythe was stunned to hear that Pogany had been sent home despite the doctor's recommendations, and even more stunned to hear Pogany would be charged with cowardice. The charge carried a possible death penalty. "Staff Sgt. Pogany was ready to work through it. But he was never given a chance," says Forsythe. "The sergeant major felt he should be charged with cowardice and sent home. And that's exactly what happened." Pogany became the first soldier to be charged with cowardice since the Vietnam War.

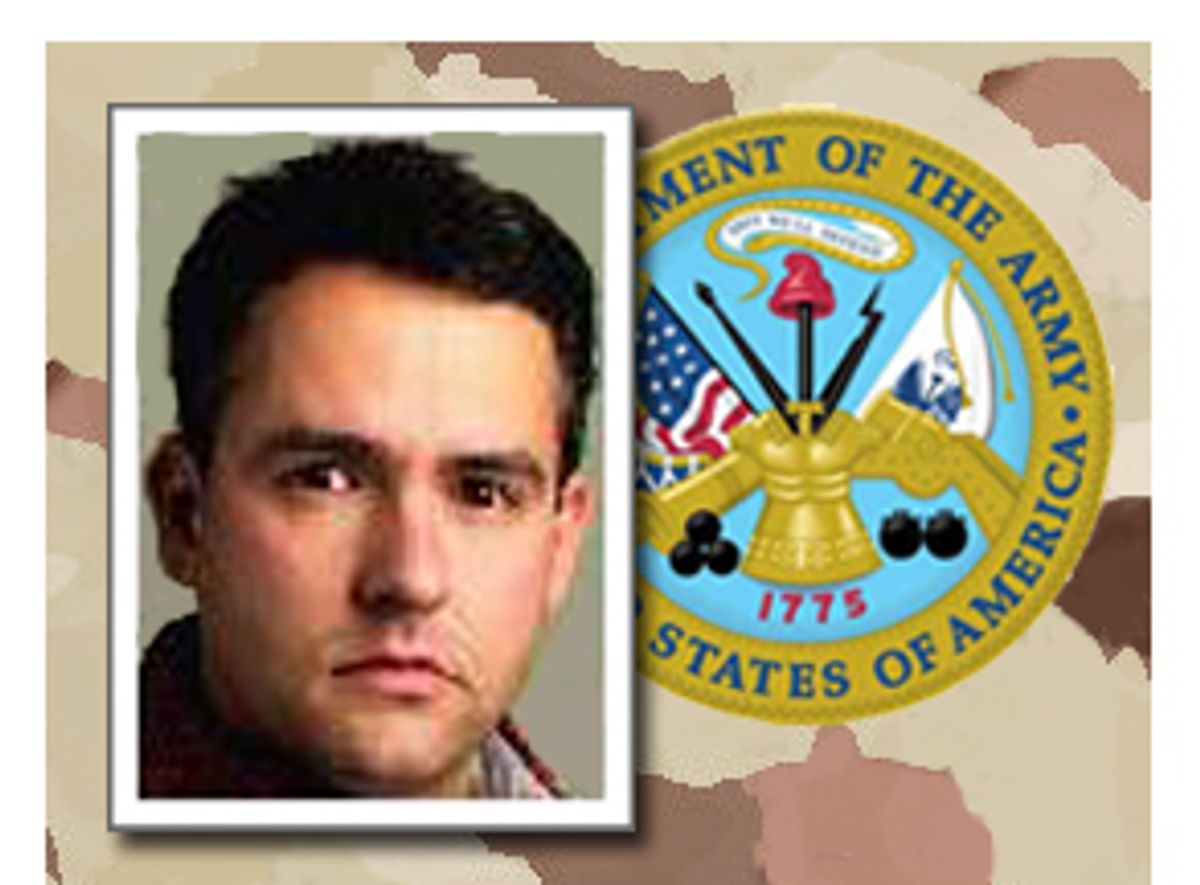

But the Army may have picked on the wrong coward. In the months since returning to his base in Ft. Carson, Colo., Pogany, 33, has refused to shut up and go away. He's fighting the military's charges against him -- charges it has repeatedly reduced. Pogany has become the poster child for how the Army treats combat stress in soldiers -- and it's a pretty ugly poster. As the Pentagon continues rotating troops and more soldiers return to civilian life, this problem will only become more pronounced. By the end of April, the U.S. military had sent more than 250,000 soldiers in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom or to Afghanistan (which has experienced similar psychiatric casualty rates).

In March 2004, the Army released a report by its Mental Health Advisory Team, which concluded that 17 percent of the soldiers serving in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom screened positive for "traumatic stress, depression, or anxiety and reported impairment in social or occupational functioning." According to Department of Defense statistics, at least 24 soldiers killed themselves in Iraq and Kuwait in 2003 -- a rate considered abnormally high and a number that several advocacy groups contend would be considerably higher if it counted soldiers who committed suicide since returning home as well as those who died of self-inflicted wounds that are still under investigation. In March, one of those suicides was a Special Forces soldier from Pogany's unit, Chief Warrant Officer William Howell, who shot himself with a .357-caliber revolver after he returned to Ft. Carson and argued with his wife. Despite the Pentagon's official stance that combat fatigue is a predictable consequence of battle that should be treated with the same seriousness as shrapnel wounds, Pogany's case illustrates that the dominant ethic of the military remains "suck it up" -- and that soldiers don't always get the help they need.

The psychological effects of combat can be devastating, as returning soldiers have learned since warfare began. Using the conservative 17 percent number from the Mental Health Advisory Team (which some think understates the severity of the problem by half), at least 42,500 soldiers who were in Iraq will likely suffer from some sort of combat stress. Yet nearly 50 percent of the military say they believe that if they report a combat-stress reaction, their careers will be in jeopardy, according to an Army survey conducted before the war.

Pogany's case serves as a very public warning to other soldiers that if they complain, they may face prosecution, ridicule and the end of their military careers. When Pogany was charged with cowardice, says Steve Robinson, executive director of the soldier advocacy group National Gulf War Resource Center, "it sent a chilling message across the Army: If you complain, you will be branded a coward." According to Robinson, many soldiers quickly decided "We're not talking about this if that's the way we get treated."

Robinson is incensed about the Pogany case, which he finds extreme but far from unique. "Pogany is the public face right now of a bigger problem," says the burly Robinson, a former Special Forces ranger. "We as a society don't understand that there are consequences when we send young men and women off to war. We have to expect that they're not going to act in a robotic manner and they will be affected by what they see and do over there."

The military has refused numerous requests for comment. "The military will not address the Pogany situation," says Rick Sonntag, an Army Medical Command spokesman. Maj. Rob Gowan, a Special Operations Command spokesman, says that because of pending legal matters, his command will not comment on the specifics of Pogany's case, either. Martha Rudd, an Army spokeswoman, says, "We certainly want soldiers who need help to ask for help and to receive help."

As for Pogany, he isn't going down without a fight. "They frigging labeled me a coward in front of the entire goddamned country," he says. Despite having run through his savings to pay mounting legal fees, he continues to challenge an institution with a $400 billion annual budget. "If I can help so one other soldier doesn't have to go through what I've been through, it'll be worth it."

Pogany believes that his behavior may have been affected by the drug cocktail that the military gives its soldiers, especially the antimalarial drug Lariam (also known by its generic name, mefloquine hydrochloride, which is what Pogany took). Lariam or its generic equivalent has been associated with the suicides of, or murders committed by, several Ft. Bragg soldiers; and several advocacy groups, as well as Congress, are investigating claims that adverse drug reactions are much more common than the military has acknowledged. "They give soldiers a little anthrax, a little yellow fever, Larium, smallpox, Ambien to help you sleep, antidepressants, whatever," Pogany says. "Any normal person would say, 'Hold on there, Hoss.'"

In late March, I met with Pogany and his wife Michelle at their friend's house in Colorado Springs, where the proximity of the Air Force Academy, Ft. Carson and Peterson AFB encourages a Taco Bell marquee to proclaim, "Thank You Troops! Welcome Home!" After work at the base, Pogany sits on a couch and painfully, deliberately, relives his story. He keeps his 3-inch-thick three-ring binder next to him, filled with legal documents, letters, sworn statements. Following his lawyer's standing advice, Pogany is careful about what he tells me, knowing that if he reveals operational security details, the military will use it against him. Next to the three-ring evidence binder sits his medical file, 2 inches thick.

He is dismissive of his biography, eager to get to his documents and his recent story. Pogany, a naturalized citizen, grew up in Germany and moved to America in 1990 as an exchange student at the University of South Florida. In 1998, at age 26, he enlisted in the Army, but he missed the initial deployment to Iraq after he injured his shoulder in an attempt to get his "jump wings" at the Army Airborne School. In late September, he was attached to a 12-man Special Forces Operational Detachment Alpha, or ODA, one week before being deployed.

As we talk, his cellphone beeps the "Mission: Impossible" theme as a steady stream of other soldiers calls to lend him support and to share intel, before he finally shuts it off. I ask why he sounds like he's from New Jersey despite growing up in Europe and spending so much time in Florida. He shrugs. Pogany looks a little like a beefy John Cusack with shorter hair, flecks of grey coming in at an accelerated rate these days.

He also displays a similar wry sense of humor as he describes the first words of the team sergeant when Pogany was introduced to his 12-man A-team: "Who da fuck are you?" As they waited in silence for a transport plane, Pogany says there was little chance to bond with his new squad. "It wasn't necessarily the time to sit around the campfire and sing 'Kumbaya.'"

He recounts his tense arrival in Iraq, being met by a Special Forces soldier who told him, "You'll be lucky to get out of here alive." He tells how his first convoy traveled the same route where a previous convoy had been ambushed. How a five-ton truck in their convoy broke down for five hours in the middle of what a highway veteran told Pogany was "Indian country." How he was driving a Land Rover the last leg after dark with a Special Forces medic who developed a strange tic, chanting Dr. Seuss rhymes from the front seat, each of them holding their M-4s on their laps, muzzles out the window. "He goes into Rain Man mode and starts reciting 'Green Eggs and Ham,'" recalls Pogany, incredulous at the surreal memory. He shut the medic up with a cigarette, and they drove through the darkness to an undisclosed location, "which was definitely not a Club Med." The compound had been attacked the previous week, and there was evidence of small-arms fire and mortar shells pocking the building where Pogany was told to bunk down. Late at night, a patrol came in after a firefight, jubilant over dead and captured Iraqis.

That's when Pogany saw the mutilated Iraqi body peeking out from a body bag. Twenty minutes later he was puking his guts out.

After being ordered out of Iraq, Pogany was flown back to Ft. Carson, spread-eagled and frisked, and separated from other soldiers. Special Forces personnel confiscated his belongings, including his laptop and satellite phone. They even took his personal gun from his home and put him on a suicide watch even though every psychiatric evaluation he had undergone specifically said that he was not a risk to himself or others. He was charged with violating Article 99 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, "cowardly conduct as a result of fear." The military dropped the cowardice charge on Nov. 6, 2003, and downgraded the charge to willful dereliction of duty.

Meanwhile, Pogany felt vilified. In a notable low point, he was watching Paula Zahn on CNN and saw a split-screen television news program that placed Pvt. Jessica Lynch on one side of the TV with the word "Hero." On the other side was a picture of him emblazoned with "Coward."

Then, on Dec. 18, the military dropped the charge of willful dereliction of duty, which would have required a court-martial, and tried to get Pogany on what is called an "Article 15 non-judicial punishment," a military procedure that allows a commanding officer to control the proceedings, including what evidence can and cannot be presented and whether Pogany could even have a lawyer present. A negative outcome would have effectively ruined Pogany's reputation and career.

Pogany declined. "I said, 'Court-martial me, then.'" In a court-martial, he'd be able to call witnesses and produce evidence, including psychologists' and psychiatrists' reports, both civilian and military, attesting to the diagnosis of combat stress and the subsequent trauma inflicted by the military's legal proceedings against him. (Pogany's diagnosis was upgraded to chronic post-traumatic stress disorder, according to a Report of Mental Status Evaluation dated Jan. 7, 2004. The report, co-signed by a civilian psychologist and an Army psychiatrist, stated, "This soldier has undergone a great deal of legal stress, which has taken a toll psychiatrically.")

As of early June, Pogany's legal case was still on hold, pending the military's next move. Rich Travis, Pogany's attorney and a former military prosecutor, says that when he inquired recently about what that next move would be, he was told, "The statute of limitations is five years." Travis suspects the military is trying to delay and goad his client to do something that will help them build a case that Pogany was a nut-bag to begin with -- since otherwise they don't have a case. "I think they're backed in a corner," Travis says. "I don't think they have many options left but to wear him down. I've never seen a soldier treated this way."

In mid-May, Pogany traveled for psychological and other medical treatment at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington. Then, last week, Pogany was diagnosed by a military doctor in California with "likely Lariam toxicity," according to medical records from the Naval Medical Center in San Diego. Pogany's records indicate that he suffered brain-stem damage (it isn't yet clear if the damage is permanent or not), and the diagnosis lends credence to the possibility that his panic attack may have been related to the antimalarial drug. (Panic attacks are known possible side effects and are listed on the drug manufacturer's warnings.) The Lariam issue is bound to grow, as more soldiers become aware of the range of possible reactions to the drug, from disorientation to loss of balance to suicide. A two-year investigation by UPI documents dozens of soldiers who appear to be suffering serious psychological side effects from Lariam. Separately, the Department of Veterans Affairs and the DoD have launched independent investigations into the drug's long-term effect on troops.

What remains abundantly clear is that the military's judicial proceedings against Pogany have delayed his receiving timely medical and psychological help. He is cautiously optimistic that, with last week's diagnosis of likely Lariam/ mefloquine toxicity, the military will now begin to help him and other soldiers recover from the psychological and pharmacological odyssey they've experienced in service of their country.

From his vantage point in Texas after finishing his hitch, former Combat Stress Control Team member Forsythe worries that Pogany's case sends a message that "your career is screwed" if you seek mental-health help, even from forward-deployed stress teams like his. What makes this especially maddening to Forsythe is that the Army's policies are totally inconsistent. He says he's helped many soldiers just like Pogany. "There's a whole population that uses us and gets on with their lives. Why are we out there with the tip of the spear if they can't come and see us? What are we there for?" The low-key Forsythe gets more animated as he considers the implications. "We're going to have a lot of people coming back who are messed up," he says. "This was a very simple case. It just got screwed up for no other reason than somebody was out to get this guy from the beginning. It shocked me."

Shares