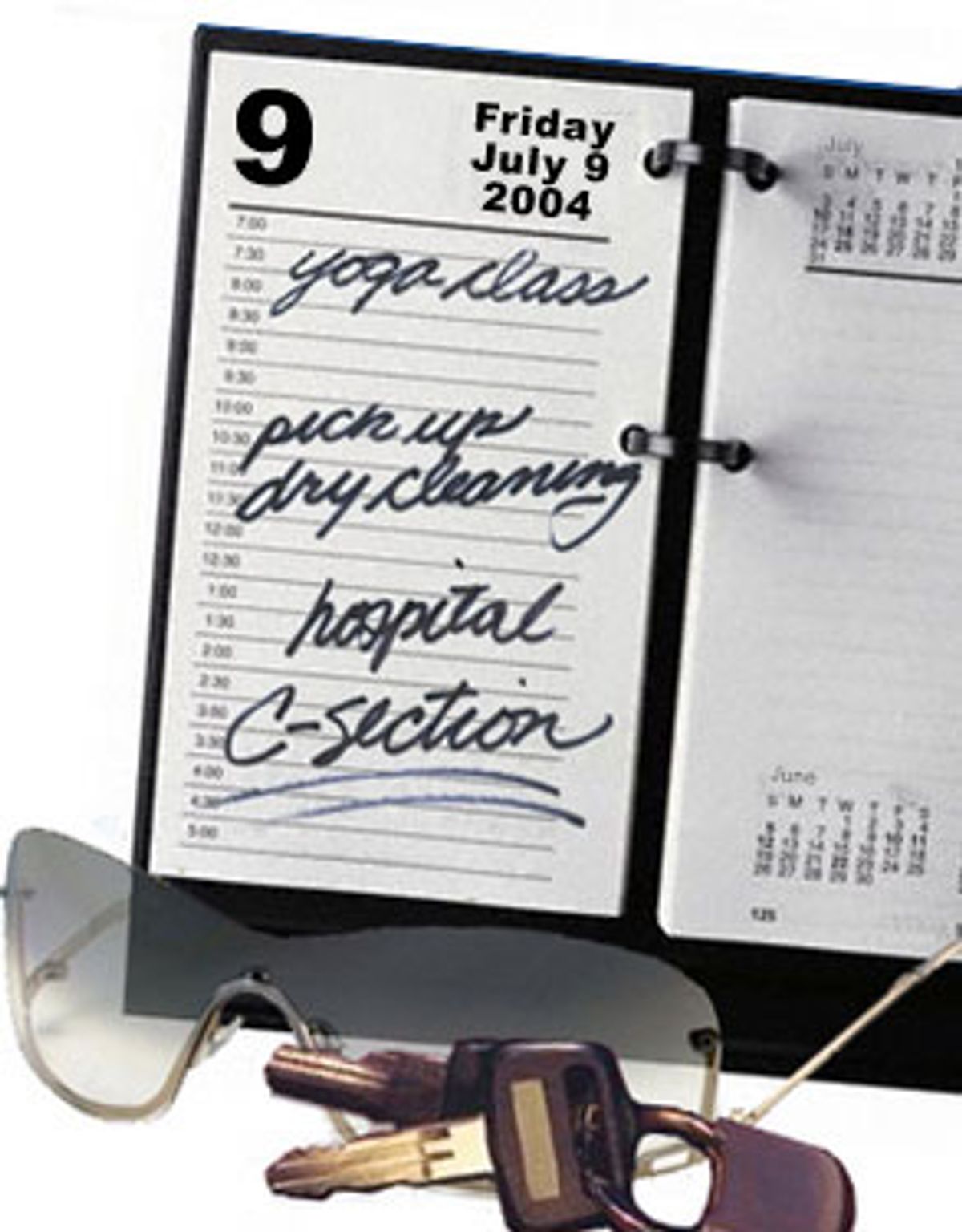

Several months after Jennifer Feeney, 34, a veterinarian in New Jersey, found out that she was pregnant, she read an article in Time magazine about celebrities such as Madonna and Elizabeth Hurley choosing to have C-sections -- not because they needed them, but because they wanted them. "I thought, Wow! That's something I'd do," she says. At her next appointment, she joked with her doctor about scheduling a cesarean birth. When he was receptive to the idea (while at the same time warning her of the risks) Feeney decided that an elective C-section was the best option for her.

"I absolutely dread the entire thought of laboring and delivering," says Feeney. "I can't see myself sitting around moaning, panting, sweating and screaming while people poke and prod at my vagina. It just seems so unnecessary to me."

Although Feeney is determined to go through with her decision, she's learned to keep her plans to herself. Her husband and doctor are supportive, but other people tell her she's "copping out." "You'd think it was the worst thing in the world to do," she says. Some other expectant mothers she's met online are horrified and have accused her of being ignorant and selfish. One woman even told her that she's going to be a terrible mother because she's only thinking of herself rather than doing what's best for her baby. "I thoroughly researched all the possible complications of C-section versus vaginal delivery and there are possible complications with both," she says. "Believe me, if I had found any statistical evidence that a C-section was worse for my baby, I would not do it."

Feeney is just one of a growing number of women across the country who are asking their doctors to deliver their babies by C-section even when they have no medical indication not to have a vaginal delivery. A study released last week by HealthGrades, a Denver company that studies healthcare quality, found that approximately 88,000 women had elective C-sections in 2002, up from about 71,000 in 2000, an increase of nearly 25 percent. "I think it would be safe to say that this is probably an under-representation of what's actually going on," says Dr. Samantha Collier, vice president of medical affairs at HealthGrades, noting that doctors may not always specify in the paperwork when a C-section is truly elective. "I don't know that it's ever going to completely replace vaginal delivery but I think it will continue to be a growing trend."

For decades, not having unnecessary C-sections was the feminist cause célèbre; can it be that having them -- a decision, like abortion, that is increasingly couched as a woman's "choice" -- is the new feminist cause?

"What the women's movement did was push for women to be able to choose a less medicalized birth, with less risk of having an intervention imposed on them that they didn't need," says Amy Alena, program director of the National Women's Health Network, a group that opposes C-sections except when they are medically necessary. "And that's the real problem with the movement for the C-section option: If it's presented to a woman as, Here are two equal options, it's no surprise that women are going to choose it. But if it's presented in what we would be considered a more balanced way, we think fewer women would be likely to choose it, because there are greater risks [with a C-section]."

According to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate of C-section is at an all-time high, with more than one out of four American women giving birth by surgery. While the bulk of this number is still made up of C-sections that are performed for medical reasons -- like a baby in breech position or with a dropping heart rate -- more and more women are requesting surgery. Their reasons run the gamut: Everything from the convenience of scheduling a birth to fearing labor, hoping to avoid a marathon delivery with complications or wanting to prevent long-term bladder, bowel or sexual problems that sometimes result from vaginal delivery.

But the optional C-section trend is making some doctors fume. "The outrageous cesarean rate we now have in this country is a national medical disgrace," says Theodore M. Peck, M.D., a perinatologist at the Gundersen Lutheran Medical Center in La Crosse, Wis., and author of "Empowered Pregnancy." "A general principle that we as doctors go by is 'Above all, do no harm.' By offering some anxious women the 'easy way out,' we are in fact potentially doing harm to some of them."

The debate over elective cesareans started publicly in the spring of 2000 when then-president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Dr. W. Benson Harer Jr., argued for "maternal-choice cesarean" in an editorial printed in the association's journal. Doctors were forced to pick a side as more patients entered their offices with requests. From 1999 through 2002, the number of elective C-sections provided to women with no previous C-section rose almost 42 percent, accounting for more than 2 percent of more than 4 million deliveries. If more women start getting their way, that number could skyrocket. In an online survey at Newshe.com, a Web site put out by sexual health experts Drs. Laura and Jennifer Berman, when nearly 2,500 women were asked, "Would you opt for a C-section over a vaginal delivery if you had the choice?" 37 percent answered "Yes"; another 9 percent answered "Not sure."

With the recent surge in prenatal yoga classes, midwives and doulas, it may seem strange that some women are opting to medicalize their births. But if a woman can decide what kind of birth control she should use, whether to get an abortion and if she wants an epidural to ease labor pains, why shouldn't she have a say in how she delivers her baby, ask some doctors and women. Proponents point to evidence showing that when healthy women choose to have C-sections, the risks, benefits and costs are balanced between C-sections and vaginal delivery. They conclude that the choice should be the mother's. Critics -- doctors, midwives and women among them -- answer back that a C-section is major surgery with risk of complications, longer recovery and potential problems with future deliveries.

If it seems like a medical community divided, it is. It hasn't helped that ACOG, which represents more than 45,000 physicians, left the issue open to debate when, last October, its ethics committee issued an official opinion on elective C-sections. After more than a year of deliberation, the group concluded that it is ethical to provide an elective C-section if the doctor believes it is in the best interest of the woman and her fetus and if he has advised her of the risks involved. If the doctor believes a C-section would be detrimental to the health and welfare of the woman and her fetus, he is ethically obliged to refrain from performing the surgery. If the patient and doctor cannot agree on a method of delivery, he should refer the woman to another doctor. The ACOG cautioned that evidence to support the benefit of elective cesarean is still incomplete and that there are not yet extensive morbidity and mortality data to compare elective cesarean delivery with vaginal birth in healthy women. In other words, the jury is still out.

Without conclusive evidence, where does this leave women who decide they want a C-section? They have little idea of how their wishes will be received by their physicians. Stories are sprinkled throughout Internet pregnancy message boards of women who have learned that they have a right to choose, but when they ask their doctors for C-sections, they are denied. It's no wonder: A recent Gallup survey of 301 female OB/GYNs showed that even women who take care of other women are sharply split. Thirty-six percent said they would not perform a C-section if a woman asked for it, 32 percent said they would, and 28 percent said it would depend on the woman's circumstances.

"I had to actually leave my OB in my last trimester to find someone who would do [the surgery], says "Millie," a contributor to the pregnancytoday.com message boards. "The entire practice I was in -- all 8 doctors -- refused to do an elective c/s for me and I would have been forced into a vaginal delivery if I had stayed there. It really does suck to be faced with no choice in how you give birth."

Risks of C-section surgery include excessive blood loss, infection, anesthesia complications, bowel blockages, and uterine adhesions that could lead to dangers in future deliveries. "C-sections are incredibly safe, but bad things can happen during medical procedures," says Dr. Jerome Yankowitz, director of the division of maternal and fetal medicine at University of Iowa College of Medicine, who is against elective C-sections unless a patient has been thoroughly counseled. "It can be unnecessary surgery analogous to liposuction. Most people have no complications, but then there are a few who do. Afterwards people think, 'Why did they do that? They weren't that heavy!'" Yankowitz says he knows of many cases of bladder damage in the mother, bad wound infections and bowel injury as a result of C-sections. Many doctors advise against elective C-section if a woman plans on having more than two children since subsequent surgeries become riskier. "Our concern is when C-sections are done a second, or third, or fourth time, you're working on a scarred area," says Marion McCartney, a certified nurse-midwife and director of professional services at the American College of Nurse-Midwives. Her organization issued a statement last fall against elective C-sections, stating that "purported benefits of cesarean section on demand are unproven and the known risks place the woman's life and reproductive future on the line."

Supporters of elective C-section acknowledge that there are risks and that a woman must be fully informed before making a choice, but that doesn't mean she shouldn't be able to choose. "There's less morbidity from C-section than there is from breast implants," says Brent W. Bost, M.D., a gynecologist in Beaumont, Texas, who has published research on elective C-sections. "We'll let women have a breast augmentation, plastic surgery and liposuction, which all have risks involved simply to look better; why will we not let them choose cesarean section?" The C-section risk data doesn't apply to elective C-sections, adds Bost, who performs about two dozen elective C-sections a year, since it comes from lumping together all C-sections. There is a difference between scheduled surgeries performed on healthy moms and those done on moms in less stable condition (for example, who've gone through hours of labor first or who have endometritis). "You've got to remember that elective C-section is a different animal," he says. "You have to compare apples to apples."

The fact that no large-scale studies have been done to compare apples to apples is what concerns nurse-midwife McCartney. "Before physicians jump in and say there are no problems with C-sections, I'd like to see a study comparing a healthy vaginal delivery to a healthy C-section," she says. "Most people think the study has been done already and it hasn't. Women think they're having an opportunity to make a choice, but what they're really getting is their provider's opinion."

Donna McDonald, a 31-year-old obstetrical nurse in Lexington, Mass., says she felt like she had all of the information she needed when she decided to schedule a C-section for her first baby last year. As a nurse, she had seen postpartum women with urinary incontinence, hemorrhoids and protruding uteruses from pushing, rectal tears, and episiotomies that had been sewn too tight. But what influenced her the most was witnessing her sister's traumatic labor and delivery, which included three hours of pushing and an episiotomy. "After I saw what she went through, I said my experience has to be very different," she says.

Choosing a C-section gave McDonald, a self-described "control freak," a sense of, well, control over the delivery. "I was concerned about birth trauma and wanted to avoid forcing my baby out," she says. "I felt the safest thing for my baby was a C-section where my doctor, who I completely trust, could be in control." The surgery went smoothly. Even the recovery, which so many people had warned her would be painful, was easier than she expected. "People told me I was crazy -- that the recovery was going to be so much harder -- that I would be laid up and need help, but I found it the opposite," she says. "When my husband and I got home I was a little bit sore and I couldn't do laundry and vacuum -- I pretty much stayed on the couch -- but I think that every postpartum woman needs relaxation time the first couple of weeks anyway."

Not all women look back on their scheduled C-sections so fondly. Many women who are forced into a C-section for medical reasons have found the recovery so painful that they question why a woman would choose to have the surgery. Stephanie Higgins, 24, had planned to have a drug-free natural delivery, but when her baby was three weeks late and estimated to be over 11 pounds, her doctor recommended that she schedule a C-section. "I feel like I missed out on an easier, more natural process," says Higgins, who couldn't get out of bed or pick up her newborn -- who, it turned out, only weighed in at 8 pounds, 15 ounces -- for days because of the pain from her cut stomach muscles. More distressing than the soreness was that she had difficulty nursing. "Since my body had not gone through labor, it took longer for my milk to come in," she says. "My baby was hungry and I had nothing for her for a good five days. It was a really difficult experience." While Higgins believes that women should have a choice how they deliver, she wishes she had been able to stick to her original birthing plan. "People say, 'I wouldn't want to go through the pain of childbirth,' but there's a lot of pain with a C-section -- and I had an uncomplicated one. The recovery was much more difficult than anyone I knew who had a vaginal delivery."

Proponents of elective C-section are more interested in talking about the mother's long-term health than the weeks after the baby is born. "The first few weeks after you have the baby is a lot different than the rest of your life," says Bost. Studies have associated vaginal delivery with higher risk of lasting consequences, including pelvic organ prolapse and urinary or fecal incontinence. "In a vaginal delivery, you stress the vagina out of proportion and then expect the muscles to come back and respond, but they may not," says Bost. "Some of us are beginning to suspect that vaginal delivery may also damage the walls of the vagina and decrease vaginal lubrication for intercourse and may also damage the nerves in the vagina that make arousal for women more pleasurable."

No one is more familiar with these distressing repercussions than the doctors who treat them. Last August, Dr. Kathleen Kobashi, a Seattle urological surgeon, told the Seattle Times that she chose a C-section because she didn't want to risk the pelvic floor problems that she fixes in other women. UCLA urologist Jennifer Berman wrote a detailed account on her Web site about why she chose a C-section with her second child. After delivering her first child, Max, she completed a reconstructive surgery fellowship and saw women who suffered from incontinence and prolapse -- where the uterus can fall through the vaginal opening -- as a result of vaginal delivery. "Had I seen patients with such problems before Max was born, I would have elected to have a C-section with him, too," she writes.

Just because a woman delivers vaginally does not mean she will experience long-term problems. But a new study of 363 women from Tel Aviv University does show that elective C-section can have a protective effect. The prevalence of urinary incontinence one year after women delivered vaginally was 10.3 percent, but for women who had an elective C-section with no labor, it was only 3.4 percent. (It was 12 percent for women who had a C-section after laboring). Dr. Alison Weidner, an OB/GYN at Duke University Medical Center who sees women on a day-to-day basis suffering from childbirth-related pelvic problems, decided she didn't want to take that risk when her doctor predicted her unborn child would weigh more than 10 pounds. "Twenty percent of women who attempt a vaginal delivery risk ending up with a C-section anyway and a C-section after labor is more risky than doing it before," she says. "The most common cause of complications following C-section is infection, including infection of the uterus and wound infections, which is highly associated with prolonged labor and prolonged rupture of membranes. By definition, if the section is performed electively, these two situations of prolonged labor and rupture of the amniotic membranes don't exist, substantially decreasing the likelihood of infection after delivery." Weidner also points to the fact that it's estimated that overall morbidity is reduced from 24 percent to less than 5 percent when C-section is performed electively, as opposed to in labor. "This is a very touchy topic," she admits. "But in my mind, it should be an individualized decision between a patient and a doctor. When you need treatment for, say, prostate cancer, you have options. I don't understand why delivery of an infant is any different."

Scheduling birth is a not a uniquely American phenomenon. In Brazil, the overall cesarean delivery rate is 50 to 60 percent and climbs to 90 percent among wealthy women delivering in private hospitals. South Korea has one of the highest C-section rates in the world, with almost half of Korean women delivering by C-section (up from 6 percent in 1985 and 21.3 percent in 1995). In Denmark, nearly 40 percent of OB/GYNs agree with the woman's right to request a C-section. But recent media coverage of Hollywood's elective C-section trend with headlines like "Too Posh To Push" (Time) have given the issue a sense of elitism. For example, actress Denise Richards told People magazine in April that she scheduled her delivery around the television taping schedule of her husband, actor Charlie Sheen. Critics are concerned that all of the hype blurs the reality of what women having surgery have to go through. "It's like any fad out there," says Meg Ferrante, a natural-childbirth instructor near Atlanta. "It sounds great and easy and fast and painless and some women enter into it excited, like it's a day at the spa."

As word spreads and more women jump on the C-section bandwagon, healthcare specialists worry about the consequences. On average, C-sections are twice as expensive as vaginal deliveries. Can maternity wards handle a rising demand for elective C-sections? Yes, says Bost, since those numbers don't apply to elective C-sections. His research, published in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, found that when you factor in nursing, medication, and monitoring during long labor, the costs of vaginal deliveries and elective C-sections balance out. He concluded, "Adopting a policy of cesarean on demand should have little impact on the overall cost of patient care."

Feeney, who is scheduled to become a mom this month, is hoping her personal choice will help pave the way for other women. "I am thrilled at the thought of planning the birth of my baby, of knowing when he'll come and being totally ready," she says. "I embrace the medical technology that will turn what could be 20 or 30 hours of excruciating and unpredictable pain into a 30-minute procedure that will birth my baby for me, with some predictable discomfort during recovery. I would not have it any other way."

Shares