"You have your period again, don't you?"

That's the first improbable question the 24-year-old heroine is asked by her first boss, the fictional old-school feminist Doris Weintruck, in Nicola Kraus and Emma McLaughlin's new novel, "Citizen Girl." That Doris, the badly coiffed, broad-of-butt founder of the imagined "Female Voice Movement," queries the book's eponymous protagonist -- yes, Girl -- while staring at her from under a bathroom-stall door is just the beginning of Girl's humiliation. Literally; it's on the first page. By chapter's end, Doris will have spilled coffee on Girl's modish coat, assigned her a snot-leaking home-schooled 5-year-old "assistant" to help her collate, forced her to work at a Self Esteem bake sale, and stolen Girl's research presentation ("Beyond Renouncing: Modeling Practical Strategies for Young Feminists"). By Chapter 2, Girl will be fired for raising her Female Voice in protest. That means that "pruney" old Doris is out of the picture, leaving space in the 11 subsequent chapters for professional degradation and marginalization at the hands of other bosses and mentors.

It's hard to be a working girl.

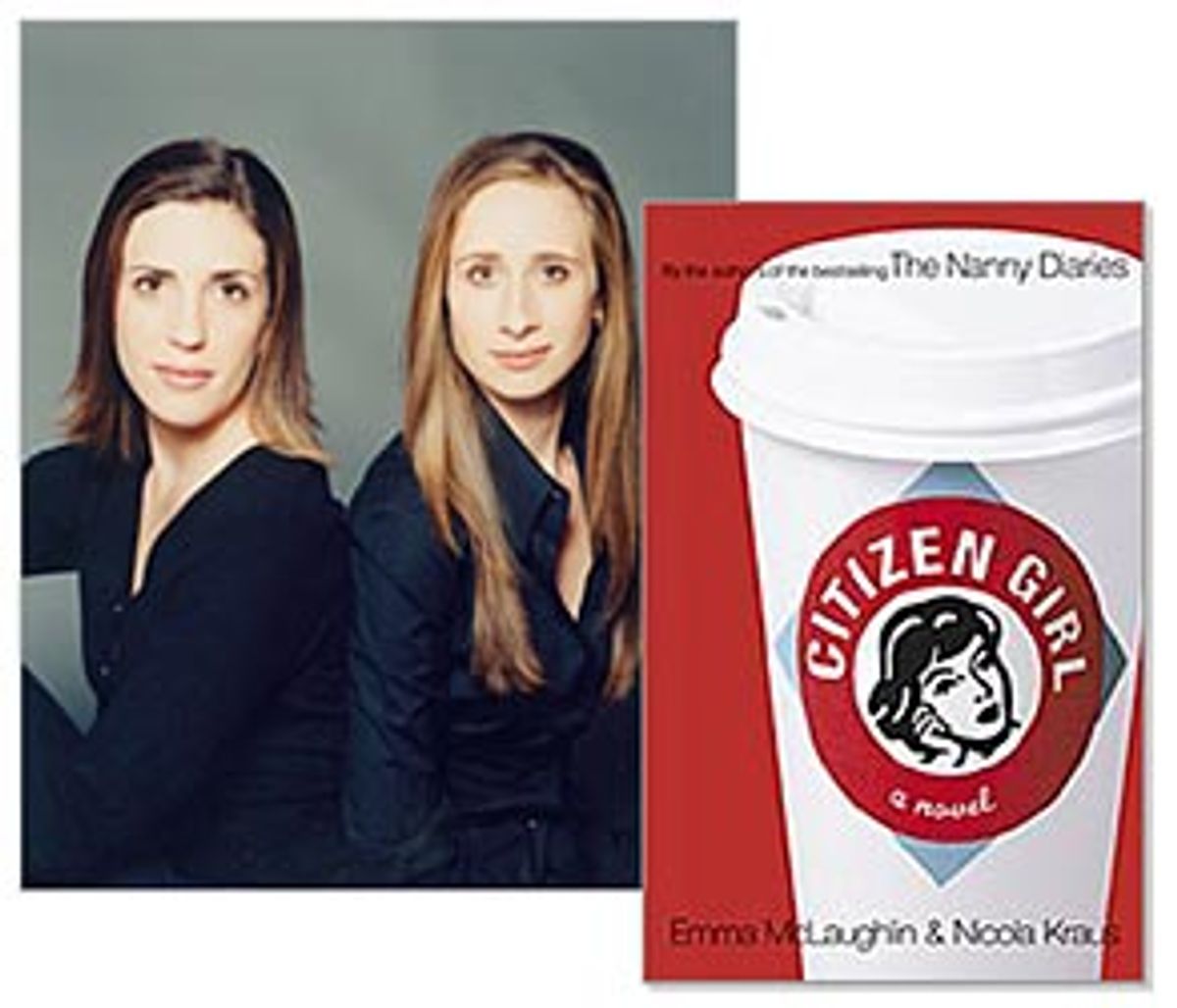

Or at least that's what Kraus and McLaughlin, co-authors of the 2002 bestseller "The Nanny Diaries," want us to believe in their second novel, which, according to the cover flap, "captures with biting accuracy what it means to be young and female in the new economy." Take out the Paleolithic reference to the new economy, and it's still a questionable claim.

In "The Nanny Diaries," former baby sitters Kraus and McLaughlin skewered the social customs and classist cruelty of wealthy Upper East Side Manhattan mommies. It was a cornerstone of the recent canon of thinly disguised tell-alls -- like "The Devil Wears Prada" and the upcoming "The Twins of Tribeca" -- that crack the shiny exteriors of hard-to-penetrate communities of power, exposing the less-attractive innards. These books serve a gratifying purpose, though not always a literary one: They provide us with detailed accounts of life in crannies of the universe most of us are unlikely ever to see firsthand. "The Nanny Diaries" -- funny, sharp and seemingly on-target -- flew off store shelves and landed its authors a $500,000 Miramax movie deal. Kraus and McLaughlin, a couple of agents later, were rewarded with a monster $3 million advance for "Citizen Girl," though they had to return the money when they handed in a draft that Random House rejected. Now "Citizen Girl" is being published by Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, which paid them a reported $200,000 for it.

What's disappointing about "Citizen Girl" isn't Kraus and McLaughlin's sophomore strikeout in the publishing industry, but the fact that what they seemed to be aiming for was actually pretty interesting: a glimpse into the professional life of an allegedly bright, politically astute woman in her 20s. Scoff all you want about the proliferation of bad chick lit, but then ask yourself: When was the last time you picked up a copy of the oft-maligned genre and found a heroine who spent more pages fretting over project proposals than marriage proposals? How many tales of young urban womanhood bother to tackle sticky generational tensions between professional women, or examine what happens when educated entitlement slams up against a photocopier? How many of them dare to dump hefty spoonfuls of the F-word -- feminism -- into their foamy narrative concoctions?

The truth is that many of us self-absorbed singletons have only intermittently active dating lives, but necessarily constant working lives. Perhaps the stories of our fractious relationships with our bosses are not as scintillating as the dramas unfolding between our sheets. But our professional triumphs and failures are what provide us with a sense of who we are -- of our personal strengths and beliefs -- not to mention our sense of how economics, politics and responsibility work in the world.

And so here is "Citizen Girl," which by dint of its successful predecessor has built-in bestseller potential. Unfortunately, the legions of female readers who are likely to pick it up will get the muddled tale of a lackluster heroine, whose insights into the plight of working women suffer in comparison to, say, Dolly Parton's 24-year-old pop song "9 to 5." Girl's experiences in what seems to be late 1990s Manhattan are simultaneously reductive and overblown, unrealistic and misogynistic, politically charged and hopelessly passé. And rather dangerously, her litany of complaints will serve only to undermine the veracity of more nuanced and very real claims about things that actually tend to go badly for working women.

After being laid off by Doris, and taking a "month-long power nap," Girl scores a job at My Company, a women's Web portal. Hired for her "feminist pedigree," she's unsure of what her job is, or what My Company does, and readers have even less of an idea. As best we can figure, Girl is supposed to make the site appealing to the Ms. Magazine crowd, and to Gloria Steinem herself, so that she will allow the Ms. archives to be added to the site. (Because nothing guarantees a mega-million-dollar profit like the Ms. archive!) Girl is also handed $1 million to bestow upon a female-friendly charity of her choice. She isn't sure how to go about this since her boss -- Guy -- is too busy shutting Girl out of money meetings and generally being loutish. Girl also has a love life in the form of Buster, a nice guy who offends Girl's feminist sensibilities by watching porn at bachelor parties, and having not-quite-consensual anal sex with her.

Girl picks a charity that rescues underage Eastern European girls who've been sold into prostitution on Long Island. And she finds a mentor in the charity's founder, Julia, a successful businesswoman who has opened her well-appointed townhouse to the destitute hookers. Julia is wealthy, attractive and stylish, qualities that help Girl determine that she is a better role model, and undoubtedly a better person, than ugly old Doris. When the wooing-Gloria plan doesn't pan out, Girl is mysteriously promoted and whisked to Los Angeles to help seduce new financial backers. Her bosses force her to get a makeover, wax her nether regions, and wear a gold string bikini to a business meeting. Eventually, a chilly businesswoman named Manley recognizes Girl's inner light, but promptly turns the company into a porn site featuring the simulated rape of one of the rescued teen prostitutes.

The book is supposed to be satire. But puffed-up, cartoonish characters and scenarios work only if they are outsize details of potent and carefully observed truths. The characters populating "Citizen Girl" are simply caricatures familiar to anyone who has reached the age of consent. There is no attention to detail; the observation of the working world is shoddy.

Young women so broke that they shower in their sinks covet Nanette Lepore skirts. When they are offered a job after weeks of unemployment they buy a Gucci coat before they've even filled out the H.R. paperwork. Efficient, communicative female bosses who inhale doughnuts and have no guilt about firing people are named Manley. Aging feminists wear Nubuck booties, "multi-colored Fimo clay glasses," and lots of batik. The man next to you on the plane reads a copy of "Barely Legal" headlined "Ouch! Eyes Too Big for Her Coochie!"

Some of these stereotypes may have seeds of truth -- batik is indeed very popular among certain women -- but they're so carelessly jampacked into these pages, and so removed from anything resembling thoughtful analysis, that they have lost even the most tenuous ties to reality. These situations simply do not ring true.

"Citizen Girl" teases us with tastes of observations that should be deliciously meaty, but wind up overcooked and bland. I'm about Girl's age, and I know that the toughest place I've ever worked was a dot-com run by two female partners who could not get along with each other. It was at this job that I began to think that sometimes women -- especially the hard-driven, shoulder-padded ones who came of age in the 1980s -- could be harder on each other, and on their younger female employees, than on their male counterparts. My bosses -- one in her 40s, one in her 20s -- had an acrimonious split and I got fired in the fallout. It was extremely unpleasant. I've had some loutish male bosses too. One who kept track of everything I put in my mouth and had me dust-busting his shoe closet the night before Thanksgiving.

It is both ludicrous and unfair to ask someone else's novel to include all the dust-busting details of my own experience. But it's a disappointing blow to any examination of the complexities facing working women when a novel so badly undercuts them. We don't need string bikinis to tell us that women make compromises to stay ahead. We don't need batik and fisting pornography to tell us that we have complicated relationships with each other and with the men in our lives. Would that there were such clear signposts to direct us to the baddies in the work world.

But most distressing is the fact that for two women audacious enough to create a self-described feminist heroine, Kraus and McLaughlin do a serious disservice to the cause. They paint a professional portrait so bleak that it makes us wonder why women like Gloria Steinem -- or Doris Weintruck -- ever fought for our right to work in the first place. Girl takes almost no pleasure in her job. Where are her kind colleagues or her funny e-mails from friends? Where is her pride, or her sense of accomplishment? Where is her satisfaction at supporting herself successfully? Based on what we learn about the world that awaits young women in the workplace, I think we'd all best stay home and pop out a few babies.

Shares