Thirty years ago, baby greens like frisée and radicchio were so exotic in the United States that Alice Waters had to sneak in seeds from Europe to plant the lettuces in her Berkeley, Calif., garden. But it's a testament to the way the country's tastes have changed since then that McDonald's is now one of the nation's largest food-service buyers of the greens, which it serves in a popular line of "Premium Salads."

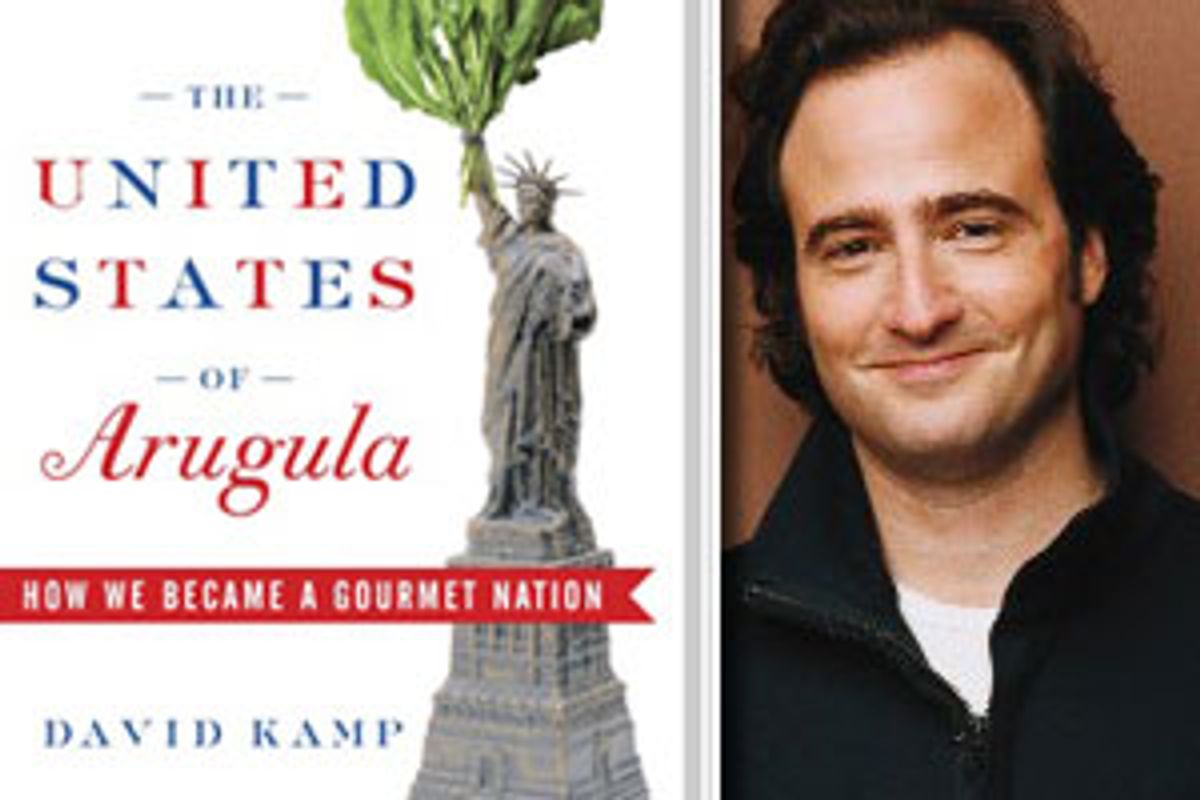

It is that extreme evolution of the American palate that journalist David Kamp chronicles in his new book, "The United States of Arugula." A writer and editor for GQ and Vanity Fair, Kamp brings a colorful pop-culture sensibility to his portrait of the personalities and places that have helped spread the gospel of good food beyond a gourmand elite and into Middle America. "Our food innovators have gotten short shrift," he explains. "But they deserve the same examination we give to rock stars -- not in a superficial way -- but as contributors to American life." To get to the heart of America's taste transformation, Kamp zeroes in on many unheralded but pivotal beginnings -- from the ocean liner that docked at New York Harbor carrying the pioneers of classic French dining in America to the friendship between Giorgio DeLuca and his neighbor, Joel Dean, that helped usher in the status food movement. And he draws upon candid conversations with both industry insiders, like cookbook editor Judith Jones and writer Nora Ephron and newcomers like Food Network starlet Giada De Laurentiis.

But the stars of "Arugula" (the "Big Three" as Kamp dubs them) are true icons of modern American cuisine: James Beard, the outsize and prolific cookbook writer who earned the title of "dean of American cookery"; Craig Claiborne, the longtime New York Times food editor who invented the concept of the restaurant review; and Julia Child, the kooky and charismatic author of "Mastering the Art of French Cooking" and star of the popular PBS show "The French Chef." Kamp details each character's relatively late-in-life culinary awakening, the historical and social milieu that allowed them to rise to fame and, most significant, the role each played in transforming cooking from a homemaking duty to a cultural pastime.

Salon caught up with Kamp recently to discuss the changing definition of "American" food, the future of celebrity chefs and why having a Starbucks on every corner isn't a bad thing.

In your introduction you make the case that it's a great time to be an eater in America. Why now?

Food is that rare field of American life where progress and innovation are so palpable. A lot of people say that music and movies aren't what they used to be. They'll point to the 1960s when the Rolling Stones and the Beatles had competing singles on the charts. But that feeling of ferment and development and fertility is what's happening with food now. Every week there's a new ingredient. Everyone is excited about jamón ibérico, the Spanish ham that's about to come to the United States. I also love seeing more and more restaurants trying to do what Dan Barber does at Blue Hill in New York -- farm-to-table cooking. And I'm dazzled by how fast it's all happening.

Don't some people -- like cookbook author Marion Cunningham -- disagree, citing the proliferation of processed foods and the fact that people don't eat at home much anymore?

I just turned 40 and Cunningham is 80. She's from a different generation. She goes back to a pre-processed-food time, when farm-to-table was an unremarkable thing. So she's looking at it from an idealized view.

Cooking was more labor-intensive then. It was able to happen because women stayed at home. It's very unfair to women to continue to expect it. If that's the cost of progress, it's not a big cost to pay. Sure, there weren't Oscar Meyer Lunchables and green Heinz ketchup. And of course, now, there are too many people who eat processed foods, and obesity is a huge problem in this country. But there's so much more variety now. We can have sushi or we can have an heirloom salad. There's a growing awareness of integrity in food. If Americans cared to -- and that's the caveat -- we could be eating better food now than any generation before us.

Is it also a great time to be a cook?

I think so. I hear conflicting reports on whether home cooking is dying out or burgeoning, but with the popularity of food TV, even college and high school kids are getting into cooking. And because of the sheer volume of ingredients and the fact that there aren't any walls up between classes and ethnicity, there's no reason why an Italian person couldn't get into cooking Japanese food.

That said, family meals are happening less frequently. People don't cook every night. It can't be expected. People eat out more; they eat prepared foods. But I don't buy into the guilt trip laid out by the food nuns. We're rushed, and we're often two-career couples. We're not a languid Mediterranean culture.

Before James Beard, Julia Child and Craig Claiborne came along, you say, America had a dysfunctional relationship to good food. What do you mean by that?

I once interviewed Robert Hughes, the art critic for Time, and he said that with art, America had a real problem with the word "elite." It's seen as a dirty word, and an un-American thing, which is ridiculous. It's the same as with food. There was always good food in America -- with what smart farmers like Thomas Jefferson were growing, and all the wild game to be had.

But the idea of culinary sophistication was really regarded suspiciously before Beard, Child and Claiborne came along. Culinary sophistication used to mean that you were not truly American or that, God forbid, you were gay. And it continues to this day, as some people like Ann Coulter talk about "latte-drinking, sushi-eating liberals," like that's all an act of sedition. It's an outdated view. But it prevailed for a long time.

You dub Beard, Child and Claiborne "food sensualists" rather than "food scientists." What's the distinction?

Part of America's dysfunctional relationship to food was a need to make food empirical. Home economics is an American discipline. It was invented by a woman at MIT. It was this idea that you could reduce, or elevate -- depending on how you look at it -- cooking into a science. The passion and the fun were taken out of it. But the Big Three really changed all that. They equated food with pleasure. They weren't really that concerned with nutrition and health -- well, maybe they were when they got older -- but first and foremost, they sought out what tasted good.

The book chronicles the rise of different cuisines in America, from classic French to California cuisine and new American. What is American cuisine?

In the 1960s, when the idea of food as culture was first emerging in the U.S., James Beard, James Villas from Town & Country and a lot of other writers had this false sense of excitement. They were trumpeting that American food was about to arrive as a cuisine, and that it could be codified. But it was naive of them to think that something like that would emerge -- as if Yankee pot roast and Maine blueberry pie could be it. I know it's a cliché, but we're a melting pot. We're also a huge spread of land, with different communities and identities. American cuisine can be a combination of a bunch of things, as long as it's authentically homegrown.

The "gourmet" and "fresh food" movement began as a way of rebelling against the food establishment, but there are still many people who would say that farmers markets and places like Chez Panisse still really cater only to the elite.

Those movements did start with an educated, worldly crowd -- with Alice Waters' Chez Panisse in Berkeley and Julia Child in Cambridge, Mass. But they have grown out of their origins. Organic food is no longer just for smug people in Northern California. I see moms in small towns buy Horizon milk because they don't want their children drinking industrial milk containing antibiotics and hormones.

These things may have elite origins, but so what? They eventually spread out and have resonance across the country. I think that's true of so many movements, like in art and in fashion. Most fashions start with the most elite people on the planet and the average American can't wait to imitate them. But when it comes to food, we throw a fit. We've got to let go of that.

The good news is that I think we are. In 20 years, more produce will be organic than not, because people will demand it. Nonorganic food will disappear, like leaded gas, and the prices will drop as a result. Food goes into your body, and you should care about how it tastes. And people are starting to embrace the idea of paying a little more for good food. Plus, good food is one of the more affordable luxuries -- a half-gallon of organic milk will only be about a dollar more than a nonorganic one.

But processed food still plays a gigantic role in our diets. Isn't it possible that the mantra about having seasonal, local ingredients served in the freshest state possible is fundamentally out of touch with the way people actually live?

I'm not an absolutist. As much as I like my seasonal summer tomatoes, I also like Jif peanut butter, and I'm not going to give it up. I think Waters was incredibly prescient. I admire her a lot, but I also think she's a little too finger wagging.

Let's face it, we live in the United States. Processed foods are never going to go away. We need to find a balance, but it's naive to think there will be a time when it will all be eradicated. We're a big capitalist culture. Companies are always going to want to make a buck. But the profile of what's in the fridge will change. We will see a shift. All these food and health stories are motivating people to care about what they eat. That's why we see the expansion of Whole Foods and Wal-Mart's embrace of organic food. It's not purely because there's money to be made. There's also a widespread demand for higher-quality products.

You quote restaurateur Danny Meyer as saying that Americans have come to follow restaurants, chefs and cooking like a "spectator sport." What do you make of this "eater-tainment"?

Some of it is silly and stupid. Gordon Ramsay and Rocco DiSpirito are talented chefs who were seduced into becoming TV show personalities. But food should be part of our entertainment and what we become passionate about -- like the music we listen to and the movies we watch. If anything, this approach to food is belated. It's an index of how integral food is to us. In countries with ancient cultures, like Japan, China and Italy, it's taken for granted that food is a cornerstone of their cultural identity. In America it's sometimes regarded as a silly thing. We like baseball and we make good music, but food is just what's for dinner. But we should care. We should know the names of chefs; they should be part of our culture.

Do you think America still has a dysfunctional relationship to good food?

America is still young. We don't have a comfort level with what we eat in a way countries with entrenched culinary traditions do. That's why the book "French Women Don't Get Fat" resonated with us so much. We lurch from fad diet to fad diet because we're not rooted in a tradition. I doubt that in my lifetime diets will go away, but the more American food improves in quality and availability and accessibility, the healthier our attitude will be toward it.

Would you say we have won the battle for good food -- or are we in the process of winning it?

It's in the process of being won. Think about how people complain that there's another Starbucks or a Jamba Juice opening up. When I was younger, coffee was by and large terrible -- unless you were in a college town and some Europeans had a cafe where they were importing good beans. Maybe Starbucks has been a little too aggressive. But they serve a superior product. And when I first started working in New York, there was only one place in the city where you could get blended juice drinks. Now there are Jamba Juices everywhere. If these places are able to keep the quality up, they're just helping spread the good word.

Shares