Judith Wallerstein's 1989 book, "Second Chances: Men, Women and Children a Decade After Divorce," made headlines and sparked controversy with its claim that the effects of divorce on children were more harmful than was generally supposed at the time. Most conservatives saw this pronouncement as a long-overdue rediscovery of old-fashioned common sense; many feminists, as an attempt to revive traditional norms especially oppressive to women. (Wallerstein rated a dishonorable mention in Susan Faludi's 1991 tome, "Backlash.") For better or worse, "Second Chances" most likely helped nudge the cultural climate toward a more judgmental view of divorce, at least where young children were involved.

The newest book from the 78-year-old family therapist, coauthored by Julia Lewis and Sandra Blakeslee, is unlikely to calm any nerves. "The Unexpected Legacy of Divorce: A 25-Year Landmark Study" delivers the bad news that the wounds of divorce are not healed by time: Indeed, Wallerstein writes, "it's in adulthood that children of divorce suffer the most."

This assertion may well produce a wave of bone-chilling dread in millions of Americans already wrestling with guilt about divorce. But should it? That depends on how much credibility Wallerstein's findings are due. Some of the problems chronicled in the book are undoubtedly real and serious. But Wallerstein's conclusions are often based on a less-than-rigorous brand of scholarship that a lot of her conservative fans would, under other circumstances, probably dismiss as "junk science."

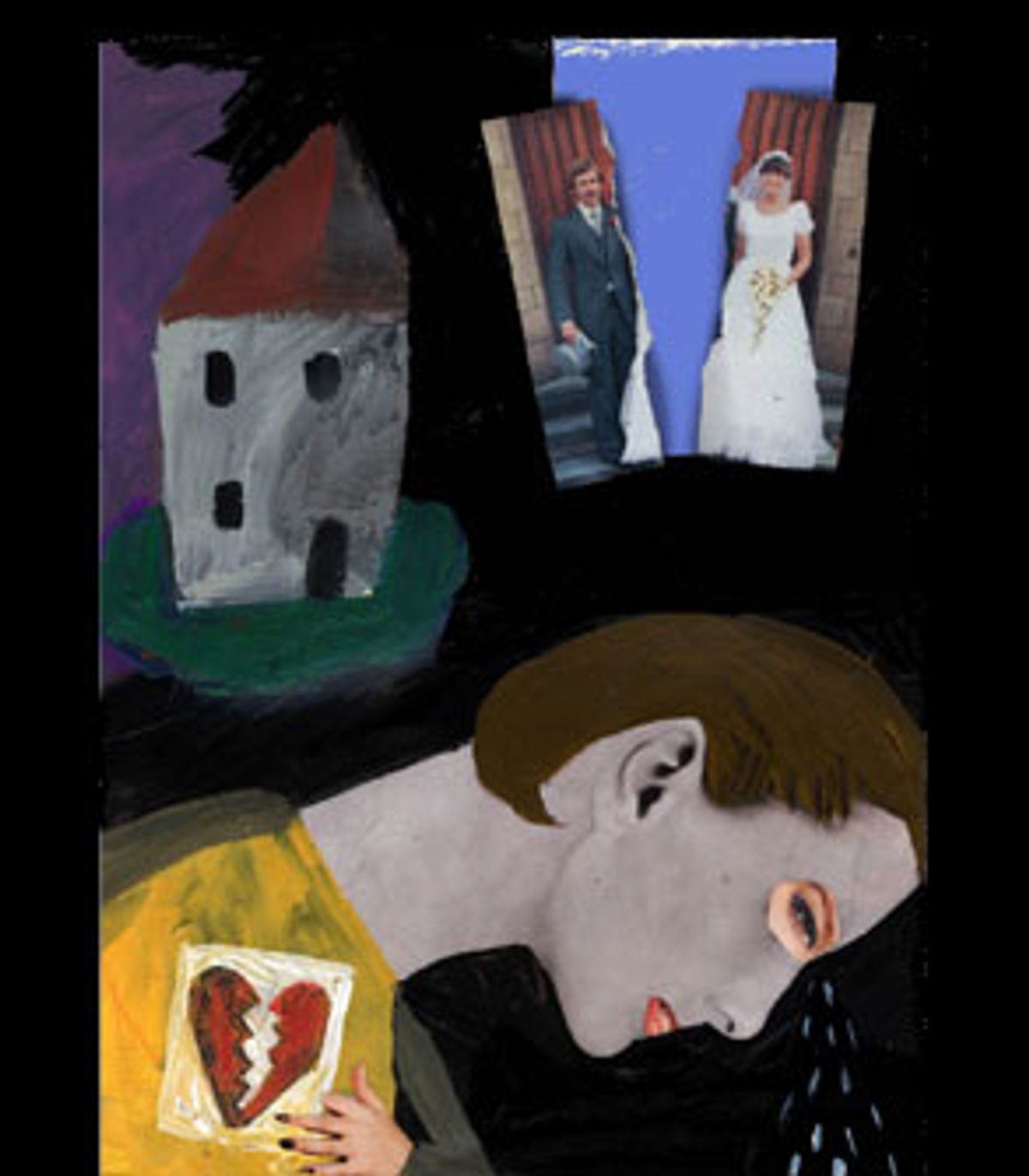

Wallerstein reports that divorce has a terrible impact on the ability of its young victims to form romantic relationships and build their own families. Children from broken homes grow up, she says, without an "internal template" of a successful partnership. "No matter how often they see their parents, the image of them together as a loving couple is forever lost ... As children grow up and choose partners of their own, they lack this central image of the intact marriage." Wallerstein notes that in her study, children of divorce, unlike their peers from intact marriages, hardly ever talked about their parents' interaction, before or after the separation.

When a parent dies, a child suffers loss. With divorce, says Wallerstein, a child must cope not only with loss but with failure: "Even if the young person decides as an adult that the divorce was necessary, that in fact the parents had little in common to begin with," she writes, "the divorce still represents failure -- failure to keep the man or the woman, failure to maintain the relationship, failure to be faithful, or failure to stick around. This failure in turn shapes the child's inner template of self and family. If they failed, I can fail, too."

As a result, some of the children of divorce whose lives Wallerstein has followed (their average age at the latest interviews was 33) have grown up to be pathological commitment-phobes, expecting all relationships to end in disaster and pain. Others, going to the opposite extreme, have rushed into reckless, spur-of-the-moment, almost invariably doomed marriages in their late teens or early 20s, or selected clearly inadequate partners who are too weak and needy to leave. Even those who are happily married remain haunted by fear of abandonment and have trouble dealing with any disagreement or conflict.

By contrast, reports Wallerstein, the young people in her comparison sample -- raised in "reasonably good or even moderately unhappy intact families" -- had a much better idea of what they wanted in a spouse and of "the demands and sacrifices required in a close relationship." Once they had tied the knot, she says, "memories of how their parents struggled and overcame differences, how they cooperated in a crisis," provided both guidance and reassurance in dealing with inevitable marital stresses and problems.

These tidy, and disheartening, conclusions beg a familiar question. What about children of never-divorced parents whose image of marriage is more Jerry Springer than Norman Rockwell? How do they fare?

Wallerstein does emphasize that if there is violence or intense open conflict in a relationship, staying together doesn't do the kids any good. However, she believes that an unhappy but bearable marriage in which both parents resign themselves to lack of marital fulfillment and "patch their relationship enough so that good parenting is maintained" is better for the children than even an amicable divorce.

Wallerstein is obviously very good at eliciting and listening to often painful intimate disclosures; she can empathize without being mushy and judge without moralizing. She is also a fine writer and storyteller who paints vivid, memorable portraits of her subjects: Paula, her idyllic childhood shattered by a messy divorce, turns to sex, drugs and alcohol as a teen, then marries a fellow alcoholic; jolted into going sober when her chaotic lifestyle endangers her son's life, she still can't shield the little boy from the fallout of her marital breakup. Billy, born with a heart defect and requiring special care, loses much of his parents' attention after they separate; as a young man, feeling "lonely and utterly unlovable," he has a series of failed relationships and almost commits suicide when his marriage falls apart as a result of his emotional unavailability.

One blurb on the back of "The Unexpected Legacy of Divorce" says that the book "reads like a compelling novel." Fair enough, but how does it rate as a bona fide "landmark study" of American divorce?

Ever since the publication of "Second Chances," Wallerstein's work has been criticized for relying on a fairly selective sample: 131 children from middle-class, overwhelmingly white California couples who were divorced in 1971. (From this original group, only 93 were reinterviewed at the 25-year mark.) In the earlier book, her conclusions about the problems that beset children of divorce were not matched against a control group of children from intact families. This time, there is a "comparison sample" of 44 young adults, recruited mainly through alumni networks at the high schools attended by subjects in the divorce study.

Findings from national studies, cited by Wallerstein in the appendix, cast further doubt on her methodology. Forty percent of adult children of divorce in her sample never married, compared with just 24 percent in the same age range in a series of national surveys. In both studies, around 40 percent of the marriages had ended in divorce.

The national data, however, show only a moderately lower prevalence of divorce for people raised in intact families (35 percent) -- whereas in Wallerstein's "intact" comparison sample, only 9 percent of the marriages had broken up. And while Wallerstein found that men and women whose parents had divorced were much less likely to have children than were those from intact marriages, national data indicate no difference in childbearing rates between the two groups.

Fellow divorce researcher Sanford Braver, a psychologist at Arizona State University and author of "Divorced Dads: Shattering the Myths" (1998), points out that Wallerstein also relies on clinical interviews rather than the standardized tests that are commonly used to measure mental well-being and social adjustment. One might say that such a critique tells us more about the biases of social science than about the weaknesses of Wallerstein's work, and that therapylike interviews can provide far better insights into what is really happening in people's lives. But such a method, Braver says, is "subjective and excessively vulnerable to the biases of the interviewer."

Even more disturbing, says Braver, is the fact that Wallerstein only rarely acknowledges that "there are literally hundreds of better designed studies that contradict some of her conclusions." In the most recent issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Joan Berlin Kelly of the University of California at San Francisco reviews research from the 1990s on the impact of divorce on children and concludes that although children of divorce do tend to fare worse emotionally, socially and academically than children from intact families, "the magnitude of the differences is quite small" and "the long-term outcome of divorce for the majority of children is resiliency rather than dysfunction."

In "The Unexpected Legacy of Divorce," resiliency is sometimes celebrated but the theme of dysfunction prevails.

Kelly happens to be Wallerstein's former collaborator on the divorce study and the coauthor of her first book, "Surviving the Breakup" (1980); today, she has strong misgivings about the direction her ex-colleague's work has taken. She has yet to read the latest book but was "appalled" by the emphasis on the negative in "Second Chances." "Judy," she says, "is very enamored of pathology."

How much of that pathology can be attributed to the parents' divorce and how much to their bad marriage? No one knows for sure. Kelly's research indicates that many of the troubles afflicting children of divorce usually predate the parents' separation by years. In Wallerstein's own novellas, it's often hard to tell if the divorce is the real culprit. One woman complains she has no idea "how to settle an argument without panicking." But what "internal template" for conflict resolution did her family give her before the breakup? "My parents were always fighting," she tells Wallerstein. "Mom was a shrieker and Dad would just walk out."

Wallerstein stresses that she is "not against divorce" and that no one has the "moral right" to tell people to stay in unhappy marriages because it's better for the kids. Nonetheless, she strongly suggests that couples beset by problems such as "infidelity, depression, sexual boredom, loneliness, rejection" should "seriously consider staying together for the sake of [the] children" if they can "maintain their loving, shared parenting without feeling martyred." Of course, that's not exactly a clear-cut guideline; the difference between martyrdom and dissatisfaction is pretty subjective. (It's also worth noting that there is ample evidence from research that children can be negatively affected by parental depression and even unspoken tension.)

While Wallerstein offers some sensible advice about things parents can do to make divorce less traumatic for children, her message is easily distilled as "stick it out." To cultural leftists such as Katha Pollitt, this suggestion is part of a backlash against post-'60s personal liberation and perhaps even against women's new freedoms, given that mothers initiate two-thirds of divorces.

Braver, who is far more optimistic than Wallerstein about the prospects for children of divorce, nonetheless agrees that parents who want to end "unsatisfying but not destructive" marriages would often do well to reconsider. But he also believes, as does Kelly, that far more attention should be paid to ways in which the detriments of divorce can be mitigated.

Recent studies suggest, for example, that children do better when both parents remain actively involved in their lives. "That gets lost in all the rhetoric about how divorce is terrible and damaging to children," says Kelly.

Wallerstein, meanwhile, takes a rather jaundiced view of divorced men's ability to be good parents. She also fails to mention that fathers today are far more likely to remain close to their children after divorce than they were in 1971.

Both Braver and Kelly support a presumption of shared custody when both parents are fit and there is no abuse or extreme conflict (which Wallerstein opposes as too rigid to meet children's needs). This doesn't necessarily mean an inflexible 50-50 schedule; it means that both parents have "substantial" time with the children -- the benchmark is that no less than 30 percent of the time is spent with the nonresidential parent -- and equal decision-making authority.

The research remains inconclusive on whether such arrangements result in better outcomes for the children. (They are definitely better for divorced fathers.) But, intriguingly, several studies have found that states with high rates of joint custody awards have shown a greater drop in divorce rates over the past decade than states in which sole maternal custody remains the norm.

One possible explanation is that when separating parents must work together on a post-divorce parenting plan, they realize that they will still have to interact with each other a lot and/or that they can communicate much better than they thought -- and end up staying together. It is also likely that, as research by University of Iowa law professor Margaret Brinig indicates, women are less likely to leave their marriages when they know they are less likely to have full custody after divorce. (Feminists who find this disturbing should ponder the fact that such a change only puts women on a somewhat more equal footing with men.)

Even if joint custody becomes the norm, any likely reduction in the divorce rate will still leave many children growing up in divorced families. And shared parenting after divorce cannot replace an intact family, if only because, as Wallerstein persuasively argues, the child no longer sees the family as a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. The loss of that wholeness is poignant. At the same time, we cannot turn away from the reality that modern marriage exists in an age of choice. As Wallerstein notes, "People want and expect a lot of more out of marriage than did earlier generations." That is why single men and women, from divorced or intact families, don't "settle" as easily as they used to; that is why spouses are less willing to tolerate wretched, loveless marriages.

Maybe some people want and expect too much. Maybe they need to be reminded occasionally that their emotional or sexual frustrations should be weighed against their children's need for a stable and secure home. On the other hand, perhaps it's not a good idea to give adult children of divorce an all-purpose excuse to blame Mom and Dad for everything that goes wrong in their lives. In any case, as Wallerstein herself acknowledges, "clearly there is no road back." As long as family and freedom both remain cherished values in our culture, it is likely that we will always be striving to maintain an often tense balance between them.

Shares