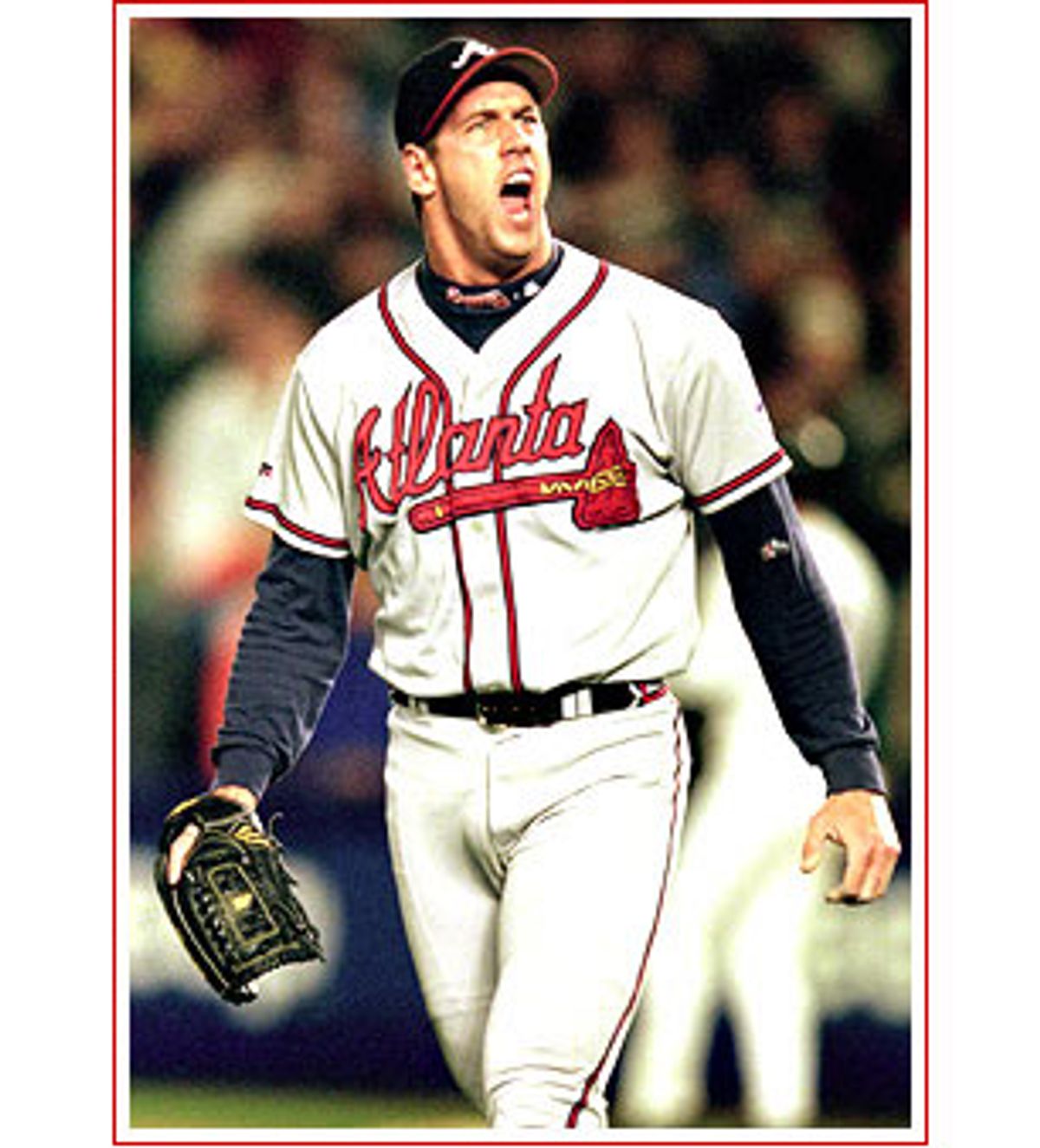

Those who first heard of John Rocker in December when Sports Illustrated reported his take on diversity in New York's metropolitan transit system entered the story in medias res. The beginning occurred months earlier, during the National League pennant race when the Atlanta Braves pitcher and New York Mets fans discovered each other and found that it was hate at first sight.

Rocker was the midnight cowboy of the bullpen who'd never been far from his home in Macon, Ga., until he signed a major league contract. His redneck swagger rubbed the Bleacher Creatures of Shea Stadium the wrong way. When he sprinted out to the mound with the game on the line, they chanted, "Asshole, asshole."

Rocker gave it back as good as he got, spitting at them when they spat at him, and letting his body language tell them that they made him sick. The fans loosed a barrage of batteries, beer bottles and other objects at Rocker when he was on the bench, tossed Coke on his girlfriend and counted the ways in which his mother had sexual congress with strange men for money. He countered by heaving fastballs into the chain link fence separating players and fans, and laughed when they cringed behind it.

It had some of the weird symbiosis of Andy Kaufman's running gag with wrestler Jerry Lawler -- a complex act based on big gestures of mutual abuse that was fated to become something more than an act. Rocker was so into his crash-dummy conquest of New York, deriving power from the hatred of strangers and reveling in the spammed hate e-mail and the foaming-at-the-mouth letters to the editor, that he was bound to do something. (At one point in his fateful interview, he chortled over his discovery that merely by calling Mets fans the degenerates he had no doubt they were, he could "make them mad enough to go home and slap their moms.")

Like the kid in the sixth grade who manages to say one funny thing and then spends the rest of the year desperately upping the ante in hopes of getting one more laugh, Rocker probably thought that he had capped them good when he gave his opinion in Sports Illustrated about the human contents of the No. 7 subway train to Shea. "Some kid with purple hair next to some queer with AIDS right next to some dude who just got out of jail for the fourth time right next to some 20-year-old mom with four kids." Just for good measure, he added that it sucks to walk for an entire block through Times Square among a bunch of foreigners who can't even speak English and that he had a black teammate who was a "fat monkey."

It is easy to imagine him mentally pumping his fist in triumph after doing his shtick. He was Howard Stern with a 95-mph fastball.

Rocker was stupid in every respect -- for dredging up such thoughts in the first place (although his picture of the demographics on the No. 7 train, some have claimed, is not far off), and especially for dredging them up in front of Sports Illustrated's Jeff Pearlman, a writer who, given Rocker's unhinged immaturity, entrapped him even by asking him to speak. Pearlman sat through a hyperventilated conversation of more than seven hours to get this good stuff. But is he Mark Fuhrman in cleats? Or is he merely an expression of the national id whose blurted-out comments represent the sinister opinions secretly held by all the rest of us?

The principal functionaries of the race industry -- Al Gore and Bill Bradley in their tacky bidding war to become the next black president, the Atlanta NAACP, Hillary Clinton in her invisible Yankees hat kissing demagogue Al Sharpton's ring, the Rev. Jesse "Hymietown" Jackson and even the rock group Twisted Sister, one of whose songs had been Rocker's theme when he came in from the bullpen -- have no doubts about Rocker's guilt, or ours. When Twisted Sister seizes the moral high ground, you know that the auditorium you're sitting in is a theater of the absurd.

These and other participants in the national monologue on race, whose guilt is passive aggressive, have shown time and again that they are willing for race to be not just a scar but a suppurating wound in this country. Scenting themselves with moral sanctimony and keeping blacks on the liberal plantation is their business as usual. What is surprising in this case is the degree to which the sports page of the nation's press has become their echo chamber.

In the good old days, sportswriting was a fan's notes -- who's about to be traded, who's not throwing well and who's getting ready to make a move late in the season, with a bit of purple prose injected before the big game. But the Rocker affair showed how complete is the woeful politicization of sports that began when John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised the fist of black power from the medal stand at the Olympic Games in Mexico City. Sportswriters were gradually infected with the desire for relevance characteristic of that era, a desire made all the more feverish by their awareness that their life's work was the toy section in the department store of life.

The politics of the sports page is for the most part lazy and unsystematic, missing or dismissing much that is truly political, especially if it conflicts with the smelly orthodoxies of race/class/gender. Thus sportswriters for the most part ignored one of the significant political stories of the last decade -- the feminists' twisting of Title IX from an equity measure able to increase female athletic participation into a mean-minded affirmative action measure that has achieved "balance" by killing off the UCLA swim team, wrestling at Princeton and other historic men's programs.

In Rocker's case, the majority of sportswriters were so busy proving that they were righteous by charging, trying and convicting the Braves pitcher that they shrugged off the implications of Commissioner Bud Selig's order to the pitcher to undergo psychological testing. Even though Selig's move smells of the auto-da-fi, the gulag, the torture chambers of Chinese political reeducation (and, for that matter, the sensitivity training forced on college freshmen every fall by America's colleges), it didn't show up on the radar screen. Rocker was placed in a classic double bind from which there was no exit: If he "passed," he was a racist; if he "failed," he was nuts.

The idea that Rocker was being punished for thought crimes made little impression. In fact, instead of criticizing the hysterical assumption that words do worse than break your bones -- a notion that should have been dispelled forever by Lenny Bruce -- most of them criticized Selig for not going further and urged Ted Turner to bring the political enlightenment he shows in other realms to bear on his baseball team by getting rid of Rocker.

Writers who can be understanding about the pressures faced by professional athletes when a wide receiver commits grand theft or murders his pregnant girlfriend pounced on Rocker's comments with fierce piety. Writing in the prose of someone who has just stepped out of a seminar on "Heart of Darkness" in the Duke English department, George Vecsey of the New York Times said that Rocker's words reflected "a deep seated hatred of the other"; that Rocker's racism is the result of "a vicious sense of displacement" coming from "deep in the heart of the national schism"; and that the rest of us should search our souls and wonder "if Rocker acted alone."

If the tone was overripe, the sentiments were widely shared. The stance adopted on sports pages across the country was similar to that of Laventri Beria, Stalin's chief of secret police, whose motto was, "You bring me the man, I'll find you the crime." When Rocker said that he had been speaking for effect, people who probably smile when Chris Rock says he loves black people and hates niggers refused to consider this possibility. When the pitcher admitted he was a fool in a muddled post-Sports Illustrated interview with ESPN's Peter Gammons, the sports establishment pronounced him insincere because he failed to admit that he was a sick bigot.

The fact that Rocker had lived with Braves' star Andruw Jones and other black and Hispanic teammates, in his own family house, for several years counted for little. And neither did the day Rocker and his father spent visiting with former U.N. Ambassador Andrew Young who concluded wisely that "nobody's perfect" and offered the pitcher advice for surviving the next season. Afterward Rocker went to see Hank Aaron, who knows something firsthand about racism, having experienced it in a virulent form during his pursuit of Babe Ruth's lifetime home run record. Initially angry at the Sports Illustrated interview, Aaron said that Rocker was "convincing."

But the sportswriting establishment wouldn't take yes for an answer. Rocker had merely apologized instead of abjectly abasing himself and crying (tears being a sign of grace for contemporary pop culture as for the readers of 18th century literature) and agreeing to shed his raunchy joie de vivre and spend the rest of his life as a pilgrim walking the rocky road of racial reconciliation. They could see only one moral in this story -- that racism, to paraphrase the old communist line, was 21st century Americanism.

The writers didn't pick up on one of the asides in Rocker's "confession" -- when he says, after being given a chance to compare himself to Latrell Sprewell, that he wonders what would happen if a white basketball player like Keith Van Horn had tried to choke his coach to death. The question of double standards is worth raising. The provision in the standard contract that Selig used to justify sentencing Rocker to psychological inquisition demands a pledge from every player "to conform to high standards of personal conduct."

What about Roberto Alomar spitting in the face of an umpire or Darryl Strawberry's endless escapades with drugs and other vices? What about Albert Belle, who is a living rebuttal to the personal conduct clause? Why haven't they been sentenced to the shrink? Why has the advent of gangsta hoops in the NBA not been a bigger story? Why didn't we hear more about the story a few years ago in which the warring "crews" attached to two players for the Philadelphia 76ers exchanged gunshots in a turf feud?

William Rhoden, another New York Times sportswriter, said that the whole Braves team should get therapy, not because of the infamous tomahawk chop that is alleged to be so hurtful to Native Americans, but because John Rockerism was rampant in baseball, and baseball has always been a metaphor for American life. Such a view was echoed by black psychiatrist Alvin Poussaint, who also weighed in on this case. Poussaint has long been an advocate of "medicalizing" racism and listing it as a disease in the profession's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. But he has never gotten very far, attributing his failure to the fact that only 3 percent of the American Psychiatric Association is black. If black psychiatrists were in control, Poussaint believes, racism would be classified and treated as a sickness.

Behind such a view is the Marxoid notion that reality is socially constructed by people with power and prejudice. The Rocker case may seem like a thin reed to hold such a heavy concept, but in fact it has become a summary moment, containing all those concepts of the past decade -- hostile environment, speech codes, race/class/gender, critical race theory, the idea that only those with power can be prejudiced -- that have made the transition from the PC academy into PC popular culture and now into the PC sports page. This was the iceberg John Rocker sailed into when he performed a drive-by shooting on himself in Sports Illustrated. And in the aftermath of the collision we can see that all the talk the case has generated about race in America is part of the problem rather than part of the solution.

Shares