Adam Jernigan's classroom is a monument to multicultural tolerance.

Prominently displayed is a copy of "Heather Has Two Mommies." A poster on one wall announces "Black power is everything." Even the student desks, each separate from the others and pointed in its own direction, seem a geographical celebration of individual creativity and difference.

The ideals of diversity and peaceful conflict resolution inspired the foundation of the New Village Community Public Charter School of the East Bay. The idea was thousands of hours in the making by parents who dreamed a better world, and who even worked to adapt an enlightened Italian early-childhood curriculum to the needs of an elementary school. In all, the planning took more than three years.

It took less time for the school to collapse. Its charter was revoked, and New Village will close at the end of this school year in June. In its short life, New Village demonstrated much of what is exciting about charter schools -- and most of what can go wrong.

Charter schools are independent public schools, cut loose from nearly all the regulations of a school district. But they are publicly funded, and hold to the basic definitions of a public school: They cannot exercise preference in admissions, cannot teach religion and cannot charge tuition. Rather than promising obedience to a voluminous education code, such schools promise results, in a document called a charter; if they fail to keep those promises, the school can be shut down.

The first charter school opened in 1992; nationally, the jury is still out on academic results at these little upstart schools, because they are so young -- most of the 1,700 operating opened in the past two years. But it's safe to say that the large majority are in far better shape than New Village, even in the inner city, where it's hardest to create an effective school.

An hour away from New Village, at the southern tip of San Francisco Bay, sits East Palo Alto Charter School, on the outskirts of Silicon Valley. Surrounded by the wealth of one of America's most economically vibrant areas, East Palo Alto, despite a recent renaissance, still presents a sharp contrast. A handful of years ago, it gained infamy as the most murderous city in the country per capita. A swarm of cops from all over the county brought the killing under control, but a police presence doesn't raise test scores. Last year, the typical East Palo Alto fourth-grader was 68 percentile points behind her counterpart in next-door Palo Alto in reading.

But in its first two years, the East Palo Alto Charter School moved from the bottom third of the district to the top third, and stands to make further gains on this spring's tests. (The scores are still a far cry, however, from Palo Alto's.) Despite the presumed benefits of self-selection the charter school enjoys, it is still working with much the same population that is struggling in other schools: Of its 312 students, 86 percent are poor enough to qualify for a free lunch. The student body is 72 percent Latino, 22 percent African-American and 6 percent "other," mostly Tongan and Samoan. One white child attends the school.

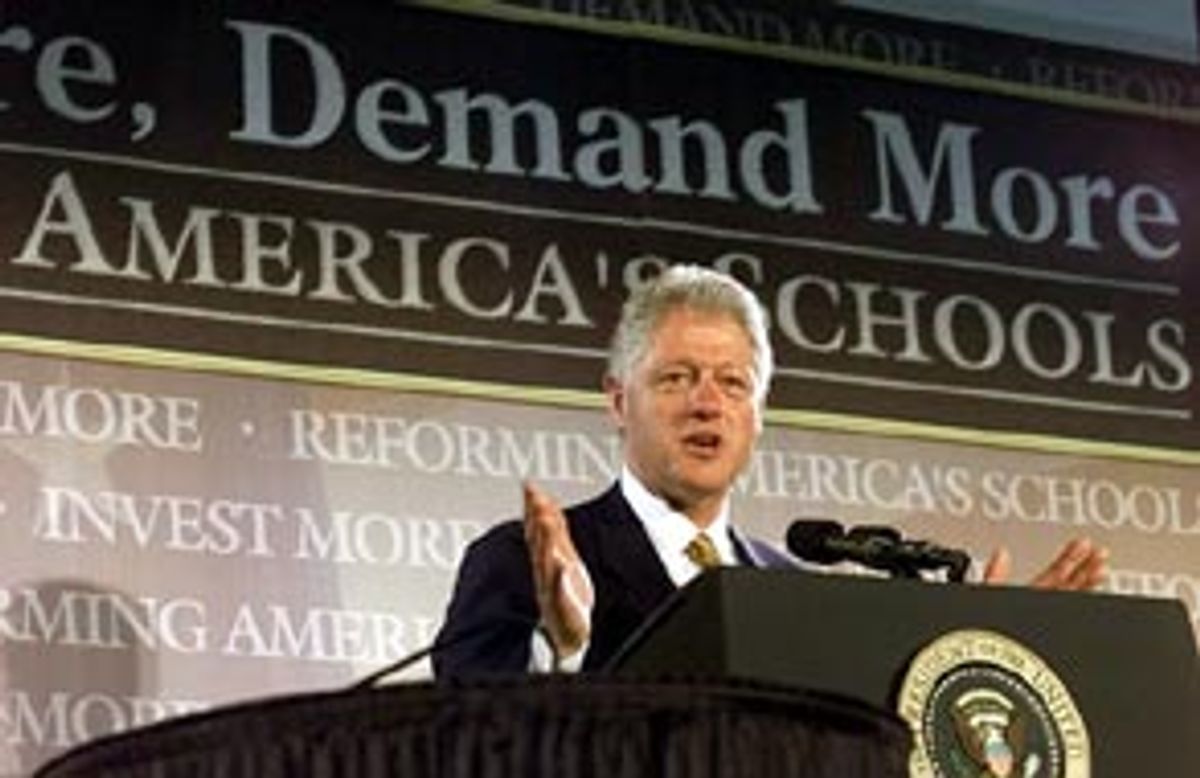

On the wings of success stories like East Palo Alto -- which owes its achievement to visionary leadership, energetic teachers and support from both parents and the school district -- expanding the number of charter schools has become a key plank for politicians of both parties. It may have seemed ambitious enough for President Clinton to call for a near-doubling of the 1,700 charter schools, to 3,000 by next year. But the candidates to replace him want to do even more. George W. Bush is calling for bringing the total to 4,000 charters in just two years, while Al Gore wants 5,000 in 10 years. Clinton wants to ante up $175 million in federal funds next year on charter schools, while Bush wants to offer $3 billion in loan guarantees.

It's not hard to understand the excitement over charter schools. Not only are they built on ideas nearly everyone loves -- freedom, escape from bureaucracy, competition and accountability -- but their early record is strong. Most parents who have children in a charter believe they are getting a better education than they used to; most charter schools have a waiting list to enroll. Charter schools, contrary to early fears, are serving a higher proportion of poor and ethnic minority children than regular public schools (though fewer special education students).

In perhaps the most important statistic, the average charter school is one-third the size of regular public schools. There's evidence that size matters; it's hardly surprising that at schools where every teacher knows every kid, students tend to be safer and to do better academically. And while it's not hard to find struggling charter schools in inner-city communities, it's also not hard to find parents in district schools who believe absolutely anything would be better than what they're getting now.

From Indian reservations to tough urban neighborhoods come inspiring reports of charter schools that have taken advantage of their freedom to make real advances -- in teaching, in bringing parents into the educational lives of their children and in making schools a base for strengthening entire communities through adult education, healthcare and social services. But as the New Village experience proves, freedom, even when coupled with dedication and good intentions, isn't always enough to make a good school.

The charter movement was still in its infancy in 1994 when parents from Berkeley and Oakland began planning New Village, a school that would be dedicated to multicultural, "anti-bias" teaching. The founders envisioned a small school where nearly every ethnic group, religion and sexual preference would be represented. Moreover, the parents wanted a school where they would be trusted partners, not supplicants to a bureaucracy that would dismiss them when their demands became irritating.

"That's what we're about, helping parents and grandparents and community activists work together to run the school," Jon Marley, a parent and spokesman, said at the time. Problems arose early in the planning, however.

The first major rift came when, like most charter schools, New Village had a hard time finding a building, and actively considered one of the few available: a ritzy women's club in one of Oakland's richest, whitest neighborhoods. The group ultimately passed on the club and decided to delay opening a year while continuing the search. But the mere consideration of the elite spot so violated the project's ideals that all four black parents on the board left.

As the grueling effort to win approval from a hostile local school board continued, so did turnover in the prospective families, so that by the time the charter was submitted, more than 100 had come and gone. Some two-score founders are praised by name in the charter for their efforts, but "most of those people's children never spent a day in the school," said Marley, a member of the pre-opening board. With the flight of so many families, the school was under pressure to recruit students, especially because charter schools get most of their funding on a per-student basis, like other public schools. And amid all the drama, the school found itself in a last-minute rush to hire teachers, a pattern that was repeated each year, with disappointing results each time.

When the school finally opened its doors in September 1997, new troubles followed. The school's governing board, an exacting group with stratospheric hopes, quickly found itself in frequent conflict with the staff. Such conflicts are not unheard of in charter schools, where the board, the principal and the founding parents and teachers each expect a large measure of authority. Another common charter challenge is fiscal woes, and New Village had more than its share, hiring more teachers and aides than it could afford, and then stripping down to bare bones, while lousing up mundane but crucial administrivia.

"The heart is there and the good intention is there, but it's the things we have to abide by -- state laws, county laws -- (with) no real formal training," said Gy Green, a parent who became board president this year. "I want this school to work. Did I know we needed to issue 1099s? No."

The problems went beyond money. With rapid staff turnover, many teachers were not fully trained in the school's curriculum. Discipline also became a battleground; where some saw free expression, others saw chaos. A traditional disciplinarian teacher, hired in 1998, became the focus of the debate, and a large group of more liberal families, many of them white, left at the end of the school year. Likewise, before the new school year began, the entire instructional staff of five quit.

When the school reopened, enrollment was not much more than half the projected 100, and the budget took a giant hit. A five-months-overdue rent check for the school building bounced. Numerous special education students weren't getting services, because there was no bus to get them there. Thanks to a bureaucratic mistake by the school, the teachers were found not to have legally required credentials.

Finally, in April, shortly before the county school board met to consider pulling the plug on New Village, the entire staff, including the principal, turned in resignations, effective at the end of the school year. Revocation of the charter became a foregone conclusion, even though the enrollment and fiscal pictures had improved markedly. In June, New Village will join that small fraction (less than 4 percent) of charter schools that have closed.

But just an hour away, in East Palo Alto, a far different story is playing out. EPACS feels like the sort of place most any parent would want to send a child. A visitor can walk into any classroom and see virtually every child actively engaged, interested, working. A very young, well-educated faculty engages in friendly but earnest competition over student performance, with an intensity reminiscent of dot-com start-ups. (Potential teachers in their mid-30s have been known to drop out of the running for a job after visiting, because they fear they can't keep up with the overachieving staff.)

With the precision of a Swiss train conductor, the principal, Donald Evans, is given to counting the number of children "off-task" every five minutes when he observes a class. Occasionally, he will use the second hand of his watch to check how much time the teacher is spending with each student. The teachers don't seem to mind the finicky attention, and have absorbed the school's ethos that teaching can be measured and improved almost scientifically. There is an air of momentum around the school's progress. Stanford University students practically compete to volunteer there, while corporate donations of cash and computer equipment are mounting.

"There's a culture here where it's not cool to slack," says Brian Auld, a first-year teacher with a master's degree from Stanford. "It's not cool to 'get by.' It's not cool to give up on kids."

But perhaps the best measure of the school's success is the involvement and satisfaction of parents, who attended a recent open house in impressive throngs. Maria Vasquez, who has three children at the school, said the charter was a welcome respite from the rudeness and screaming of teachers at the district school they previously attended. "They're doing more with the children," she said. "I don't see them treating the children bad like in other schools."

Danny Thompson, a father of three who also serves as technology coordinator for the charter school, said teachers and administrators elsewhere had told him that his kids, while well-behaved, weren't cut out for success. "We're proving to them, day by day, that our kids can achieve," he said. "We've taken those kids and raised them up."

No charter school has an easy beginning; East Palo Alto, which like New Village opened in 1997, had a rough first year, complete with battles with parents, problems with some teachers and even a roof collapse. But what made the difference for East Palo Alto were several crucial assets: a strong, visionary principal who knew exactly what he wanted his school to look like, and who could rally families and teachers; school district support and solid start-up funding from philanthropist John Walton and the School Futures Research Foundation; an unremitting focus on recruiting the brightest teaching candidates available; the willingness of parents who had chosen the school to help run it; and, as principal Evans frequently points out, a healthy dose of luck.

Focusing on examples like East Palo Alto, advocates argue charter schools not only will themselves be better, but will force improvements in the larger system through competition. Charter advocates would call New Village a success of sorts, because it got shut down when it was in trouble, in contrast to failing district schools.

But as President Clinton, a charter fan, acknowledged this month, in remarks at the nation's first charter school in Minnesota, "Some states have laws that are so loose that no matter whether the charter schools are doing their jobs or not, they just get to stay open, and they become like another bureaucracy."

And charter schools also face challenges all their own. For one thing, they force their leaders, who are usually educators, to run not just a school but a small business. That's especially tricky because charters, in contrast to regular public schools, get no public money for a building in most states. That means they either must find a sugar daddy or a free building or must cut deeply into funds meant to buy books and pay teachers. (And even with money, many would-be charter schools are having great difficulty finding space in urban areas.)

Also, charter schools typically receive no funds until children arrive. That leaves schools in a Catch-22 over how to pay for the careful planning that is so crucial before the school opens. And when the school does open, it frequently must figure out how to share power with parents and teachers -- and as New Village found, that's no small challenge.

Moreover, with politicians murmuring "charter schools" like a mantra, pressure is mounting to create lots of charters, fast. That's a little like demanding to make good wine, fast. What charter schools primarily offer is freedom to do something different. It's what people do with that freedom that counts. It takes hard work, brilliant ideas, good organization and commitment. And sometimes, as parents at New Village now know, even that isn't enough.

The day after the ax fell there, Sheila Jordan, the Alameda County school superintendent, offered a eulogy that could unnerve those contemplating opening a charter school. "I think the lesson here," she said, "is that good, strong educational ideas don't necessarily carry the day when it comes to making a small charter school work." Jon Marley, the ex-board member and school spokesman, spoke wistfully of the idea behind the school. "I still think that the vision was really beautiful," said Marley, whose children now attend a regular public school in Berkeley. "I just think we didn't have the ability to carry the vision into reality."

Yet it's telling that even people who know the anguish of a failed school haven't soured on the charter concept. Green, the board president, hopes to resubmit the charter and reopen the school. "It still is a great idea," she says. The current principal -- the third the school has had -- is thinking of starting another charter school. And teachers Gina Hill and Adam Jernigan, chatting on a recent Friday afternoon, were giving serious thought to working in one.

"I think they're a great idea," said Hill, who is considering following the principal to her new charter. Jernigan agreed. "I think they're a fabulous idea."

"I think they're a great idea," said Gina Hill, who is considering following the principal to her new charter. Jernigan agreed. "I think they're a fabulous idea."

Shares