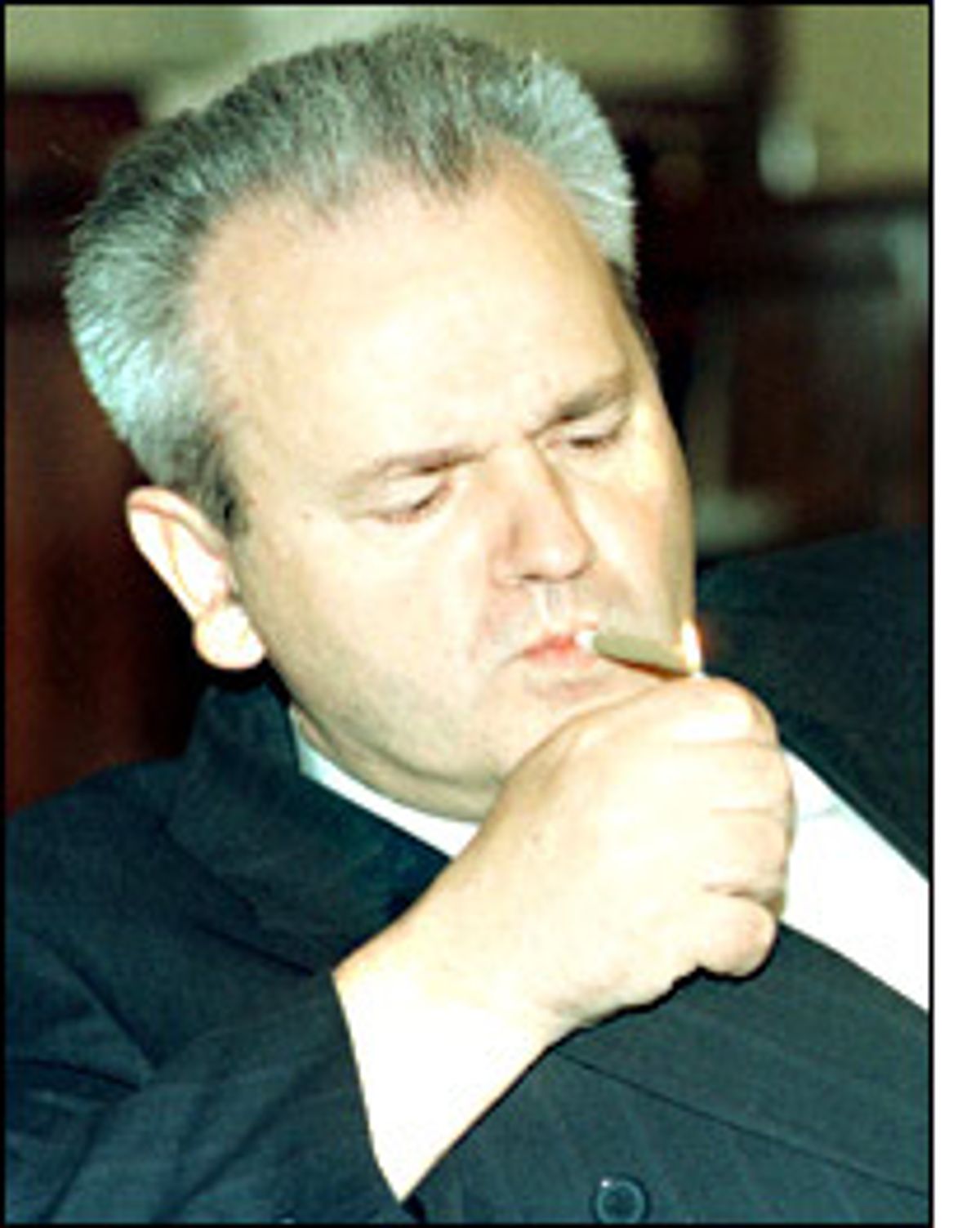

Ethnic clashes in northern Kosovo. Fear of war in Montenegro. Money mysteriously moving from foreign bank accounts back into the Serbian regime's coffers. It must be that Slobodan Milosevic is preparing for elections.

It is the opposition's worst nightmare: Having demanded early elections all year, now Milosevic looks set to call them, but under the worst possible conditions.

Milosevic normally prepares for elections by distracting and worrying the population with violence -- in Kosovo, in Montenegro -- which scares enough of the old people to vote for the strongman. Then he gets ahold of some of the millions of dollars the regime stole from Yugoslav banks years ago and stashed in foreign bank accounts, and brings it back in time to pay off pensioners, the police, army and anyone else on the state payroll.

This year Milosevic has another potential target group of new voters for his Socialist Party: some of the 700,000 Serbian refugees who have been displaced by his failed war bids in Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo, and who are living miserably in Serbia.

Suddenly, some 50 of these poor refugees a day are being granted Yugoslav citizenship, according to opposition politician Goran Svilanovic. What's the implicit catch? That they vote for the man who gave it to them.

Milosevic has recently managed to get hold of enough hard currency to stave off hyper-inflation for the next six months, so that he can pay off pensioners, police and the army and hold elections within that time. According to leading dissident economist Mladjan Dinkic, some $300 million mysteriously moved from China to Belgrade in December. The regime first tried to explain the money as a gift of the Chinese government, then coyly suggested it was a loan.

"It could not be a gift, that's for sure," says Dinkic, who heads the G17 group of independent economists in Belgrade. "Because China does not give financial gifts, it's not that rich. My opinion is this is money of Serbia's political establishment that was transferred abroad, first to Cyprus, and other countries, and then to China, and it was being repatriated here in December."

The value of the Belgrade-Chinese relationship -- which has blossomed in the wake of NATO's accidental bombing of China's Belgrade embassy last spring -- became clear this week, as Milosevic ordered his Socialist Party branch offices to begin preparing their "voter rolls" for elections, possibly as early as later this month.

Under the Yugoslav constitution, Milosevic must call Serbian local and Yugoslav federal elections by November. Serbian parliamentary elections -- perhaps most critical for unseating Milosevic's ruling coalition -- are due to be held in 2001, but the opposition has been demanding that they be held this year as well.

The pillars of Milosevic's election strategy are making payoffs and creating a fear of war among his population. Not only does he have the Chinese government loan at his disposal, but he is also benefiting indirectly from the United Nations oil-for-food program for Iraq -- which allows Saddam Hussein to sell about $1 billion worth of oil a year and use the cash to buy humanitarian supplies of food and medicine. Recently, a key Yugoslav military procurement agency was granted permission to sell $100 million worth of wheat to Iraq. In fact, the Yugoslav company is the very same one that the U.S. meant to hit when it accidentally hit the Chinese embassy.

Analysts have wondered how, after his loss of Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo, Milosevic could manage to find some place with which to cause another conflict and distract his population of 10 million impoverished, war-weary and sanctions-burdened people from blaming him for their misery. He has found two ways.

His special forces have infiltrated northern Kosovo, in particular the northern Kosovo city of Mitrovica, and he has put many Serbs in that ethnically divided city on Belgrade's payroll. Thus he has found agents for continuing to stir up ethnic violence even under a Kosovo controlled by 50,000 NATO-led peacekeeping troops.

Last week at least 10 people were killed and dozens injured in the worst clashes in Kosovo since the war ended in June. Milosevic stokes the flames by having his generals promise that the Yugoslav army will return to Kosovo this summer if NATO continues to permit this "genocide" against the Kosovo Serbs -- a promise they are unlikely to be able to fulfill, but this is election season.

Milosevic is playing an even subtler game with the pro-Western, independence-minded smaller Yugoslav republic of Montenegro -- but the subtlety could end in more violence.

Western governments are encouraging Montenegrin President Milo Djukanovic to slow down his move toward independence, out of fear it will provoke Milosevic to clamp down with an army coup against Montenegro. But Milosevic is actually pushing Montenegro out. The border between Montenegro and Serbia has been entirely shut by Serbian police since last week. Milosevic is also reported to be arming his supporters in Montenegro. He knows that NATO will find it extremely difficult to intervene in a civil war in Montenegro, but it would be under tremendous pressure to intervene to protect Montenegro should Serbia attack it.

The assassination of Yugoslav Defense Minister Pavle Bulatovic at a Belgrade restaurant Monday added to growing speculation that Milosevic is trying to provoke a civil conflict in Montenegro in order to rally support behind him at home. Bulatovic, a pro-Serbian Montenegrin, comes from northern Montenegro, where many of the people tend to support Belgrade over the independence aspirations of Djukanovic.

Recently, there were reports that the Milosevic government was covertly arming these pro-Serbian factions in Montenegro and Bulatovic, as defense minister, would have been a natural vehicle for these activities. Bulatovic was also reported to have been the organizing force behind demonstrations by pro-Belgrade tribes in northern Montenegro.

Analysts believe that the killing of Bulatovic could be the spark for pro-Serbian Montenegrins to seek revenge against pro-independence Montenegrins -- and there are fears of a possible revenge assassination attempt against Djukanovic, and against the pro-Montenegrin former head of the Yugoslav army, Gen. Momcilo Perisic, who has become a staunch critic of the Milosevic regime.

What's an opposition desperate to get rid of Milosevic to do?

Having recently overcome their differences, Serbia's political opposition parties have decided they will come to a decision together on whether to boycott or participate in elections.

Zarko Korac, a liberal Belgrade psychology professor and a leader of the opposition Social Democratic party, says the opposition must fight and win even under Milosevic's rigged rules. Essentially, the opposition must win unfair local elections, because that is all they are likely to get.

Economist Dinkic agrees. If the opposition manages to win some towns, and Milosevic tries to cheat and declare his ruling coalition the winner, Dinkic believes outrage will drive people onto the streets, and the massive anti-government demonstrations his opponents have been trying to mobilize all year will happen.

And many think that scenario is actually possible. Frustration with Milosevic has reached such a massive level, many opponents believe, that this attempt to preserve the illusion of legitimacy through elections may be one of his last. A poll released by the independent Serbian magazine NIN this week shows that roughly two-thirds of Serbs think Milosevic's Socialist Party of Serbia has failed to fulfill its promises, and had conducted a disastrous foreign policy. About the same number couldn't name a single achievement of the party over the past 10 years.

Shares