Vladimiro Montesinos' world is shrinking.

In hiding, facing imminent arrest in Peru, the world famous ex-spy chief reportedly sent a cryptic message Friday asking for the safety of house arrest if he were to turn himself in. This comes after the Peruvian government announced last week that it would launch a probe into allegations that Montesinos laundered more than $48 million through Swiss banks, and that he could face prosecution on illicit enrichment charges.

Just over a month ago Montesinos, the former head of Peru's National Intelligence Service (SIN), notorious for repeated human rights abuses, fled his country after videotapes surfaced showing him bribing an opposition legislator to change sides in favor of his boss, Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori.

When Montesinos took the step taken by so many other fallen villains before him -- taking off for Panama in a private jet -- he expected the same reception they had been given. But Panama's president, Mireya Moscoso, refused him asylum on Oct. 22 -- the first time in Panamanian history that the country refused to serve as the "trash bin for other nation's cast-off leaders," in the words of Miguel Antonio Bernal, a law professor and leader of a popular movement that mobilized to pressure the government into denying Montesinos sanctuary.

And that was just the beginning. When he arrived in Guayaquil, Ecuador, that evening on what he thought was a secret flight back to Peru, he was met instead by a blizzard of television cameras and the flashbulbs of news photographers. The press had been tipped off by a man who had gained the upper hand in an extraordinary rivalry. Latin America's most notorious spymaster had been handed a humiliating defeat by one of Peru's leading investigative journalists, Gustavo Gorriti.

The world has learned of Montesinos' brutal reign over Peruvian politics only recently. But for more than a decade Gorriti was chronicling his corrupt rise to power, and the human rights abuses committed by his security forces, in the Peruvian newsmagazine Caretas. Eventually he fled the country after death threats were isued against himself, his wife and his young daughter.

The tale of these two men, who grew up in the same neighborhood in the southern Peruvian city of Arequipa, now has the makings of a magical realist tale. Their personal rivalry has played a central role in kicking off the tragi-comic soap opera that accompanied Montesinos' return to Peru. For when Montesinos made his frantic exit from Peru on Sept. 26 and landed in Panama City, he arrived, like a figure from a Mario Vargas Llosa novel, in the very country to which he had forced his journalistic nemesis into exile.

Montesinos would soon discover that Gorriti had not faded into the obscurity of exile. Since arriving in Panama City in 1996 -- after stints as a Neiman fellow at Harvard and with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, as well as writing for the New York Times and the New Republic -- he has been associate director of Panama's leading newspaper, La Prensa. During his tenure in Panama, he has inspired dramatic improvements in the nation's journalistic culture, leading La Prensa investigations into money laundering, arms dealing and corruption.

In 1997, Panama's then-President Ernesto Balladares attempted to have Gorriti deported after a series of embarrassing exposés. That effort was derailed after the newspaper's staff defied efforts by the police to oust him from La Prensa's office -- they created a round-the-clock phalanx of support, with Gorriti barricaded inside -- and protests flooded in from journalists around the world.

Gorriti's fury at Fujimori and Montesino's increasingly authoritarian rule led him to take a three month leave from La Prensa last spring to advise the opposition candidate, Alejandro Toledo, whose accusations of fraud in the presidential election helped spark the current crisis in Peru.

Within days of Montesinos' arrival in Panama City in September, Gorriti was on his tail, and the extraordinary saga of these two men's battle began to play out in the pages of La Prensa.

The newspaper revealed the extent of Montesino's business and real estate holdings in Panama, and revealed the fact that he applied for, and received, a residency permit (expired by the time he arrived) from the previous government. La Prensa chronicled his continuing attempts to influence events back home in Peru, and reiterated his abuses of power there, including evidence for prosecuting him in Panama under the Convention Against Torture -- which provided the legal basis for the case against former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet.

In one particularly memorable exchange in early October, after La Prensa's business editor identified a bank in Panama City as having received millions of dollars in deposits from Montesinos, a top official with the bank denied the allegations and accused Gorriti of "conflict of interest" in his handling of the story due to the two men's history in Peru. Gorriti fired back in defense of his editor, on the paper's editorial page, with the numbers of the accounts, and offered a spirited defense of crusading journalism.

"Does a journalist threatened with reprisals by the Mafia stop covering the Mafia because he thinks there will be a conflict of interest?" he wrote. "If [Montesinos] is here, he is laying down the gauntlet for journalists to investigate and shine the public spotlight, and we will continue to tell his story."

Indeed, La Prensa's coverage created an unparalleled public awareness of Montesinos' presence in Panama. From Parliamentarians to taxi drivers, Montesinos has been on the tip of everyone's tongue. The uproar marked a contrast to the last dictator who sought refuge here, Raoul Cedras of Haiti, who was given asylum quickly by President Balladares last year, and who has since faded into the comfortable rhythms of elite Panamanian society.

There is every reason to believe Montesinos expected the same soft landing. Recent reports had him seeking to purchase an entire Panamanian island off the country's Caribbean coast with the estimated $200 million he is thought to have stolen from the Peruvian treasury, or accumulated through drug, arms and money laundering deals that marked his reign at the top of Peruvian intelligence.

"People of most countries do not like the idea of a criminal moving in next door," comments Reed Brody. As advocacy director of Human Rights Watch, he flew to Panama City in mid-October to meet with top government officials on the Montesino case.

"But to get to that point, they have to know what's happening. Usually, they just move in, settle down, no one knows. Gorriti followed the issue, he put it before the Panamanian public. La Prensa's coverage enabled the natural revulsion of people against human rights abuses to come to the fore."

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

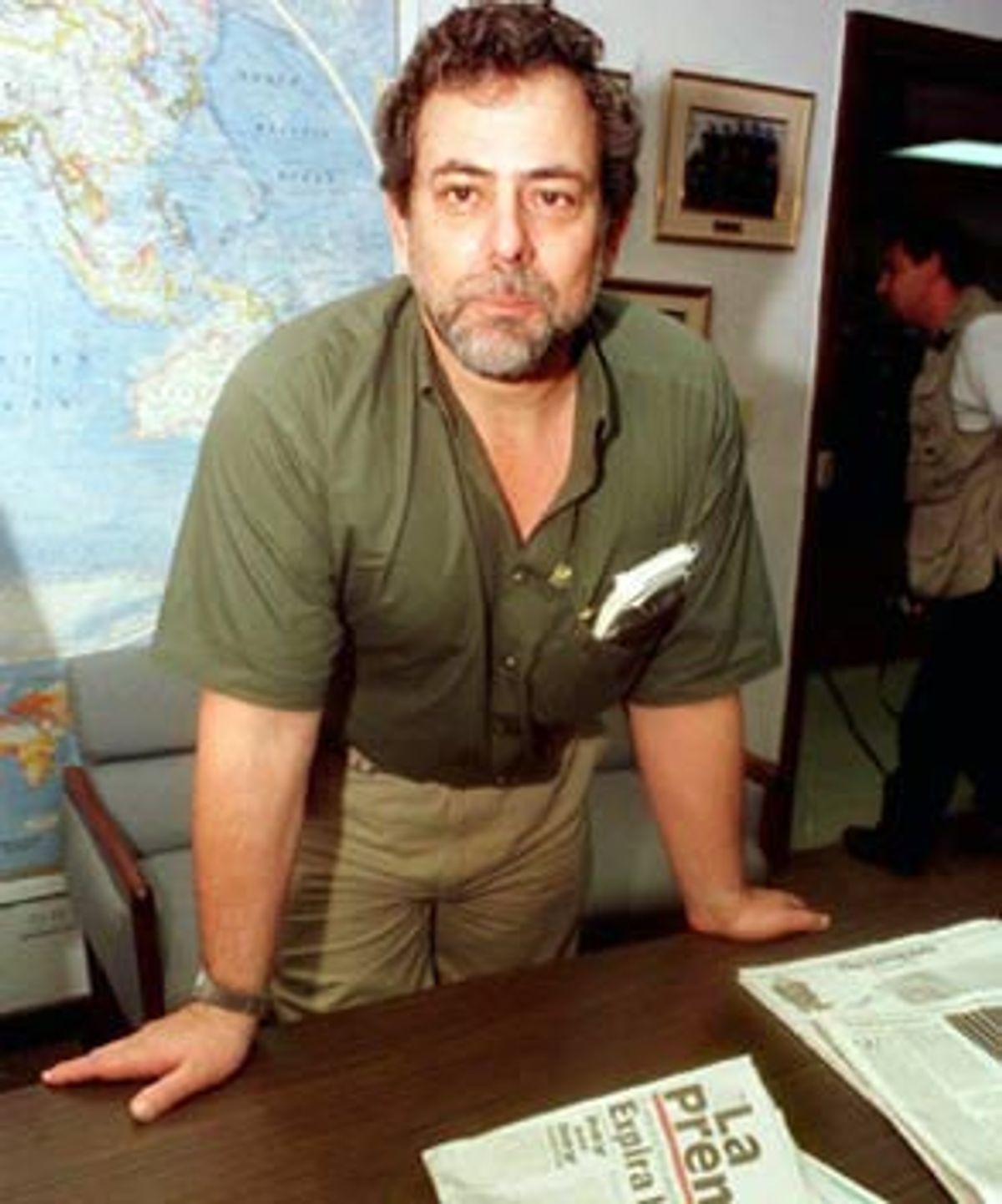

Sitting in his office in La Prensa one recent evening, Gorriti cuts an impressive figure. He is genial, intense, a bit stocky, bemused at the twist of fate that threw his enemy back into his sights. He laughs at how he and Montesinos seemed to have come full circle.

"We are reproducing our old relationship," he says. "I keep looking for him, and he keeps hiding from me. I try to put the spotlight on him, and he keeps trying to stay in the shadows."

On that night two weeks ago in Ecuador, their rivalry came to a head. Shortly after Montesinos took off, Gorriti received a tip from a reliable Panamanian source telling him that Montesinos was heading home, via Ecuador. The flight, on a private jet owned by Marc Harris -- an infamous American expatriate offshore financier with extensive business interests in Panama -- was supposed to be clandestine.

Gorriti phoned a friend at Peru's only independent television channel, Channel N, with the news. "They put me on the air," Gorriti recalled a few days after the incident. "I told Peru on Sunday night, 'Vladimiro's on the way.' When he landed in Guayaquil, the place was swimming with media." Within minutes of Montesinos' arrival, Gorriti was interviewed on several of Peru's leading radio stations. The story received coverage on CNN Español, and quickly hit the wires across Latin America and the world.

The blanket coverage derailed Montesinos' plan to land in Lima. Instead, his plane headed straight for a secure air force base in Pisco in southern Peru.

But it was too late. By the time he arrived, Montesinos was greeted by the sight of himself, being broadcast on television, his own beak-nosed, pinched visage plastered onto masks of thousands of demonstrators in Lima and elsewhere demanding that he face prosecution for the many human rights violations associated with his SIN tenure.

His arrival kicked off the surreal saga now unfolding in Peru, with Fujimori charging off on a quixotic search -- or an absurd pantomime of a search, as Fujimori critics say -- for his former aide. Gorriti comments, "Those two, they've been so intimate with each other for so long, it's like one side of a string trying to find the other side of the same string."

Montesinos is now a man on the run, dodging the ostensible efforts of his former patron to find him, fearful of prosecution from a judicial system that he for years twisted to his own ends.

"Montesinos should not receive protection in Panama from a justice system [in Peru] he helped to create," asserted Marco Ameglio, chairman of the foreign affairs committee of Panama's National Assembly in an interview last month. The government's decision was a remarkable political event, defying the requests of the United States, 11 Latin American nations and the Organization of American States that it grant Montesinos asylum -- on the grounds that it would speed Peru's transition to democracy.

In addition to Gorriti, Montesinos is haunted by the legacy of former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. Montesinos' status as the world's leading pariah illustrates how inhospitable the world has become to human rights abusers in the wake of the international legal assault against Pinochet, which established the principle of prosecuting torturers outside of their own national territory.

"Pinochet has changed the way everybody thinks about justice," comments Brody, one of the chief strategists behind Human Rights Watch's legal offensive against Pinochet. "The norm used to be you brutalize your people and plunder the treasury. Then go off somewhere to retire. Now, you can't do that. Countries may actually go off and arrest you."

If Montesinos had stayed in Panama, he might very well have faced a legal challenge. Panamanian human rights activist Miguel Antonio Bernal filed a complaint in early October on behalf of several of Montesinos' victims, demanding that he be charged with violations of the U.N. Convention Against Torture (which provided the legal standing for the Spanish case against Pinochet).

Three additional complaints have also been filed with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights from Peruvians claiming to have been victims of Montesinos-orchestrated brutality -- two from the families of tortured and murdered former SIN officials, a journalist who was tortured in a SIN facility and a former general who revealed the existence of a death squad run through the intelligence agency. Another complaint concerns the abduction and murder of nine students and a teacher from Peru's La Cantuta University in 1992.

Refuge for Montesinos anywhere in the world now appears highly unlikely. Requests for sanctuary in Brazil and Argentina were rejected even before Montesinos' flight to Panama. On Oct. 20, while Montesinos was still in Panama, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights took a dramatic step in distancing itself from the pro-asylum position taken by Cesar Gaviria, chairman of the Organization of American States. The commission, formerly a branch of the OAS, expressed its disagreement with Gaviria by recommending that "member states of the OAS ... refrain from granting asylum to any person alleged to be the material or intellectual author of international crimes."

Under intense public pressure, last week Fujimori even withdrew a proposed amnesty for human rights abuses by the military and security forces overseen by Montesinos.

Thus, Montesinos finds himself in a situation eerily similar to that of former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic before his fall from power. With dwindling options, he holds onto the final cards in the deck -- loyalists in the military and the specter of a coup -- and pushes against the growing public protests calling for him to be brought to trial.

Does Gorriti harbor the slightest respect for his longtime adversary? "No. To respect an enemy, you must find nobility. Montesinos has astuteness. He has ruthlessness, he has a lack of scruples. He has treachery imbedded in his every molecule. His greed is enormous. But nobility, not at all."

Gorriti still sees their rivalry in almost military terms. "It is a battle that will end when one of us ceases to breathe," he says. "But I believe now the war is over, and he has lost. He will live life like a pariah, in a smaller and smaller world."

Gorriti continues to monitor events closely as they unfold in his native Peru, and hopes, perhaps, to return there as a journalist after a democratic transition. As Fujimori headed off on the hunt for his former bagman, Gorriti said, "Peru is changing through comedy, through farce, but it is changing. In my case, knowing these characters, I might be pardoned to sit and watch these events and smile."

Shares