Writer Susan Sontag has produced many texts during her four-decade career, including historical novels and reflections on cancer, photography and the war in Bosnia. But it was a brief essay, less than 1,000 words long, in the Sept. 24 issue of the New Yorker that created the biggest uproar of her life. In the piece, which she wrote shortly after the terror attacks of Sept. 11, Sontag dissected the political and media blather that poured out of the television in the hours after the explosions of violence. After subjecting herself to what she calls "an overdose of CNN," Sontag reacted with a coldly furious burst of analysis, savaging political leaders and media mandarins for trying to convince the country that everything was OK, that our attackers were simply cowards, and that our childlike view of the world need not be disturbed.

As if to prove her point, a furious chorus of sharp-tongued pundits immediately descended on Sontag, outraged that she had broken from the ranks of the soothingly platitudinous. She was called an "America-hater," a "moral idiot," a "traitor" who deserved to be driven into "the wilderness," never more to be heard. The bellicose right predictably tried to lump her in with the usual left-wing peace crusaders, whose programmed pacifism has sidelined them during the current political debates. But this tarbrush doesn't stick. As a thinker, Sontag is rigorously, sometimes abrasively, independent. She has offended the left as often as the right (political terms, she points out, that have become increasingly useless), alienating some ideologues when she attacked communism as "fascism with a human face" during the uprising of the Polish shipyard workers in the 1980s and again during the U.S. bombing campaign against the Serbian dictatorship, which she strongly supported.

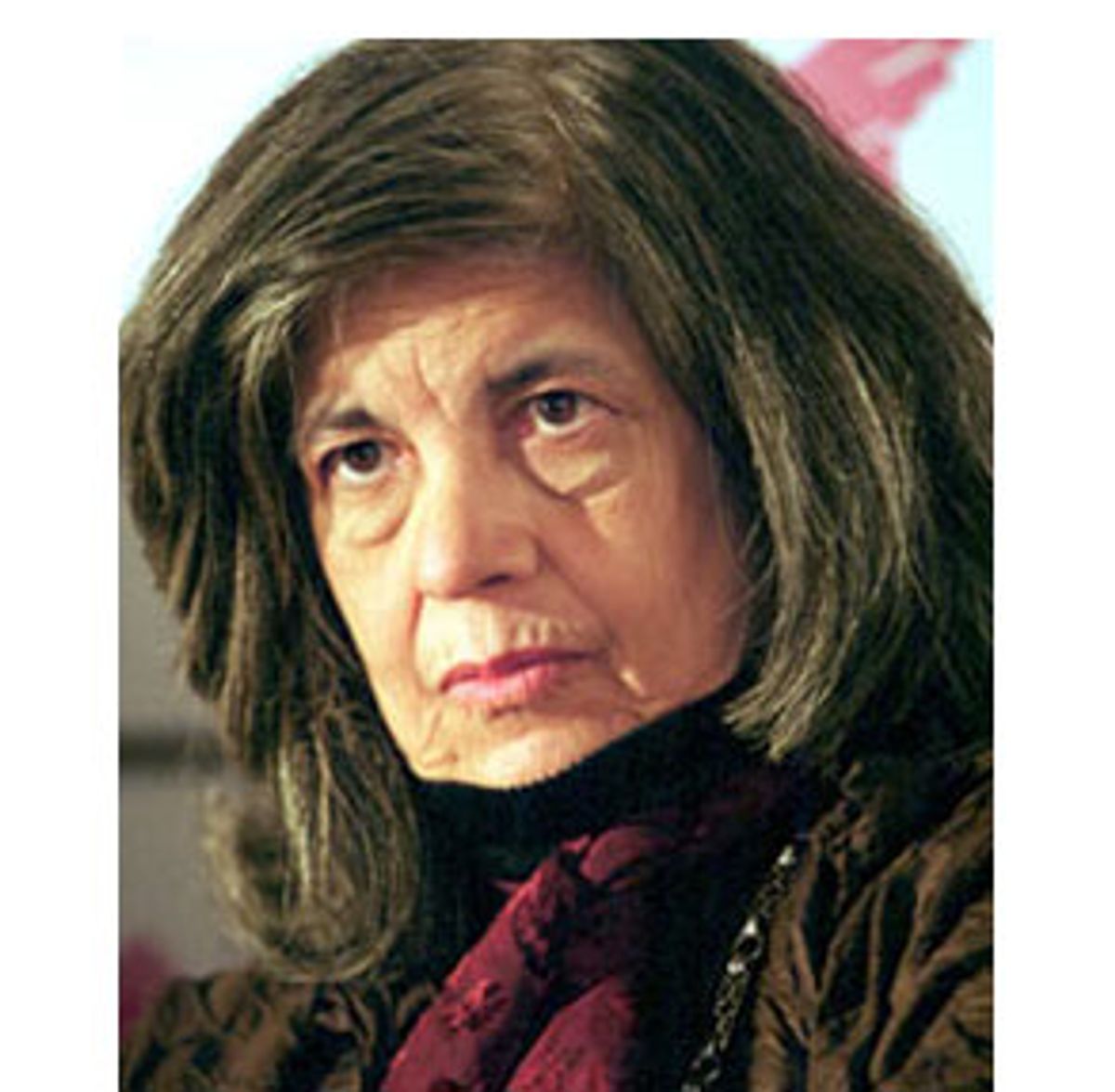

Sontag, 68, remains characteristically unrepentant in the face of the recent attacks. On Monday, she talked with Salon by phone from her home in Manhattan, reflecting on the controversy, the Bush war effort and the media's surrender to what she views as a national conformity campaign.

Did the storm of reaction to your brief essay in the New Yorker take you by surprise?

Absolutely. I mean, I am aware of what a radical point of view is; very occasionally I have espoused one. But I did not think for a moment my essay was radical or even particularly dissenting. It seemed very common sense. I have been amazed by the ferocity of how I've been attacked, and it goes on and on. One article in the New Republic, a magazine for which I have written, began: "What do Osama bin Laden, Saddam Hussein and Susan Sontag have in common?" I have to say my jaw dropped. Apparently we are all in favor of the dismantling of America. There's a kind of rhetorical overkill aimed at me that is astonishing. There has been a demonization which is ludicrous.

What has been constructed is this sort of grotesque trinity comprised of myself, Bill Maher and Noam Chomsky. In the Saturday New York Times, Frank Rich tried in his way to defend us by arguing for our complete lack of importance, by saying that any substitute weather forecaster on TV has more influence than any of us. We were identified as a writer, a late evening comic, and a linguistics professor. Sorry, but Noam Chomsky is a good bit more than a "professor of linguistics." Our critics are up in arms against us because we do have a degree of influence. But our own "defenders" are reduced to saying, "Well, leave the poor things alone, they're quite obscure anyway. "

Look, I have nothing in common with Bill Maher, whom I had never heard of before. And I don't agree with Noam Chomsky, whom I am very familiar with. My position is decidedly not the Chomsky position

How do you differ from Chomsky?

First of all, I'll take the American empire any day over the empire of what my pal Chris Hitchens calls "Islamic fascism." I'm not against fighting this enemy -- it is an enemy and I'm not a pacifist.

I think what happened on Sept. 11 was an appalling crime, and I'm astonished that I even have to say that, to reassure people that I feel that way. But I do feel that the Gulf War revisited is not the way to fight this enemy.

There was a very confident, orotund piece by Stanley Hoffman in the New York Review of Books -- he's a very senior wise man in the George Kennan mold, certainly no radical. And I felt I could agree with every word he was saying. He was saying bombing Afghanistan is not the solution. We have to understand what's going on in the Middle East, we have to rethink what's going on, our foreign policy. In fact, since Sept. 11, we're already seeing the most radical realignment of policies.

Bill Maher has abjectly apologized for his remarks --but you don't seem to be getting any more docile in the fact of this storm of criticism. Why not?

Well, I'm not an institution, and I don't have a job to lose. I just get lots of very nasty letters and read lots of very nasty things in the press.

What do the letters say?

That I'm a traitor. The New York Post, or so I've been told, has called for me to be drawn and quartered. And then there was this Ted Koppel show -- the producer invited me onto the show a week ago. It's not my thing, but I did it. And they got someone from the Heritage Foundation [Todd Gaziano], who practically foamed at the mouth, and said at one point, "Susan Sontag should not be permitted to speak in honorable intellectual circles ever again." And then Koppel said, "Whoa, you really mean she shouldn't be allowed to speak?" And he said, well maybe not silenced, but disgraced and "properly discounted for her crazy views."

So there's a serious attempt to stifle debate. But, of course, God bless the Net. I keep getting more articles of various dissenting opinions e-mailed to me; naturally, some of them are crazy and some I don't agree with at all. But you can't shut everyone up. The big media have been very intimidated, but not the Web.

I don't want to get defensive, but of course I am a little defensive because I'm still so stunned by the way my remarks were viewed. What I published in the New Yorker was written literally 48 hours after the Sept. 11 attacks. I was in Berlin at the time, and I was watching CNN for 48 hours straight. You might say that I had overdosed on CNN. And what I wrote was a howl of dismay at all the nonsense that I was hearing. That people were in a state of great pain and bewilderment and fear I certainly understood. But I thought, "Uh-oh, here comes a sort of revival of Cold War rhetoric and something utterly sanctimonious that is going to make it very hard for us to figure out how best to deal with this." And I have to say that my fears have been borne out.

What do you think of the Bush administration's efforts to control the media, in particular its requests that the TV networks not show bin Laden and al-Qaida's video statements?

Excuse me, but does anyone over the age of 6 really think that the way Osama bin Laden has to communicate with his agents abroad is by posing in that Flintstone set of his and pulling on his left earlobe instead of his right to send secret signals? Now, I don't believe that Condoleezza Rice and the rest of the administration really think that. At least I hope to hell they don't. I assume they have another reason for trying to stop the TV networks from showing bin Laden's videotapes, which is they just don't want people to see his message, whatever it is. They think, Why should we give him free publicity? Something very primitive like that. Which is ridiculous, because of course anyone can see these tapes for themselves online, via another TV news network abroad. Although I see the BBC, our British cousins who are of course ever servile, are discussing whether to broadcast the tapes. We can always count on the Brits to fall in line.

Why has the media been so willing to go along with the White House's censorship efforts?

Well, when people like me are being lambasted and excoriated for saying very mild things, no wonder the media is cowed. And self-censorship is much more widespread than one can imagine. Here's something no one has commented on that I continue to puzzle over: Who decided that no gruesome pictures of the World Trade Center site were to be published anywhere? Now I don't think there was single directive coming from anywhere. But I think there was an extraordinary consensus, a kind of self-censorship by media executives who concluded these images would be too demoralizing for the country. I think it's rather interesting that could happen. There apparently has been only one exception: one day the New York Daily News showed a severed hand. But the photo appeared in only one edition and it was immediately pulled. I think that degree of unanimity within the media is pretty extraordinary.

What is your position on the war against terrorism? How should the U.S. fight back?

My position is that I don't like throwing biscuits and peanut butter and jam and napkins, little snack packages produced in a small city in Texas, to Afghan citizens, so we can say, "Look, we're doing something humanitarian." These wretched packages of food that are grotesquely inadequate -- there's apparently enough food for a half-day's rations. And then the people run out to get them, into these minefields. Afghanistan has more land mines per capita than any country in the world. Neither is it anything less than dangerous to the recipients of our so-called generosity to drop packages of medicine on people who have no access to doctors and no knowledge of how to use these. That wonderful organization, Medicins sans Frontieres [Doctors Without Borders], has denounced this practice.

I'm sickened by the way that the delivery of so-called humanitarian aid is once again being used as a justification -- or cover -- for war.

As a secular person, and as a woman, I've always been appalled by the Taliban regime and would dearly like to see them toppled. I was a public critic of the regime long before the war started. But I've been told that the Northern Alliance is absolutely no better when it comes to the issue of women. The crimes against women in Afghanistan are just unthinkable; there's never been anything like it in the history of the world. So of course I would love to see that government overthrown and something less appalling put in its place.

Do I think bombing is the way to do it? Of course I don't. It's not for me to speculate on this, but there are all sorts of realpolitik outcomes that one can imagine. Afghanistan in the end could become a sort of dependency of Pakistan, which of course wouldn't please India and China. They'd probably like a little country to annex themselves. So how in the world you're going to dethrone the Taliban without causing further trouble in that part of the world is a very complicated question. And I'm sure bright and hard-nosed people in Washington are genuinely puzzled about how to do it.

Do you really think it could be done without bombing?

Absolutely. But this would be a complicated, long set of operations, some of them military and covert, and the United States is not very experienced in these matters. The point is, as I said in my New Yorker piece, there's a great disconnect between reality and what people in government and the media are saying of the reality. I have no doubt that there are real debates among military and political leaders going on both here and elsewhere. But what is being peddled to the public is a fairy tale. And the atmosphere of intimidation is quite extraordinary.

And I think our protectors have been incredibly inept. In any other country the top officials of the FBI would have resigned or been fired by now. I mean, [key hijacking suspect] Mohammad Atta was on the FBI surveillance list, but the list was never communicated to the airlines.

The authorities are now responding to the anthrax scare -- most probably domestic copycat crazies on their own warpath -- by spreading more fear. We have Vice President Cheney saying, "Well, these people could be part of the same terrorist network that produced Sept. 11." Well, excuse me, but we have no reason to think that.

As a result of these alarming statements from authorities, the public is terrified. I don't know what it was like in San Francisco this last weekend, but I live in New York and the streets were empty after the FBI announced that another terrorist attack was imminent. You have these idiots in the FBI saying they have "credible evidence" -- I love that phrase -- that an attack this weekend is "possible." Which means absolutely nothing. I mean it's possible there's a pink elephant in my living room right now, as I'm talking to you from my kitchen. I haven't checked recently, but it's not very likely. And meanwhile our ridiculous president is telling us to shop and go to the theater and lead normal lives. Normal? I could go 50 blocks, from one end of Manhattan to another, in five minutes because there was no one in the streets, no one in the restaurants, nobody in cars. You can't scare people and tell them to behave normally.

We also seem to be getting contradictory messages about Muslims in the U.S. We're told that not all Islamic people are our enemy, but at the same time there's a fairly wide dragnet, which some civil liberties defenders have criticized as indiscriminate, aimed at rounding up Islamic suspects.

Well, people are very scared and Americans are not used to being scared. There's an American exceptionalism; we're supposed to be exempt from the calamities and terrors and anxieties that beset other countries. But now people here are scared and it's interesting how fast they are moving in another direction. The feeling is, and I've heard this from people, about Islamic taxi drivers and shopkeepers and other people -- we really ought to deport all the Muslims. Sure they're not all terrorists and some of it will be unfair, but after all we have to protect ourselves. Racial and ethnic profiling is now seen as common sense itself. How, it's now felt, could you not want that? If you're going to take planes, you don't want to find yourself sitting next to a fellow in a turban and a beard.

What I live in fear of is there will be another terror attack -- not a sick joke like the powder in the envelope, but something real that takes more lives, that has the stamp of something more professional and thought out. The target could be another building with a resonant, symbolic-sounding name, this time in Chicago or some other heartland city. If that happens, we could have something like martial law. Most Americans, who as I say are so used to not being afraid, would willingly accede to great abridgements of freedom. Because they're afraid.

You called the president "robotic" in your New Yorker essay. But the New York Times, among other media observers, has editorialized that Bush has shown a new "gravitas" since Sept. 11. Do you think the president has grown more commanding since the terror attacks?

I saw that in the Times -- I love that, "gravitas." Has Bush grown into his role of president? No, I think he's acquired legitimacy since Sept. 11, that's all -- I don't call that "growing" at all. Let's not forget, the election was stolen for him. I think what we obviously have in Washington is some kind of regency, run presumably by Cheney and [Defense Secretary Donald] Rumsfeld and maybe [Secretary of State Colin] Powell, although Powell is much more of an organization man than a real leader. It's all very veiled. And Cheney has not been much seen lately -- is this because he is ill? It's all very mysterious. I hate to see governance become even more opaque.

It seems important to the Times and other major media to shore up the president's image these days.

Yes, I just don't understand why debate equals dissent, and dissent equals lack of patriotism now. Still, there are reasons to cherish the Times. I cry every morning real tears, I mean down-the-cheek tears, when I read those small obituaries that the Times publishes of the people who died in the World Trade Center. I read them faithfully, every last one of them, and I cry. I live near a firehouse that lost a lot of men, and I've brought them things. And I'm genuinely and profoundly, exactly like everyone else, really moved, really wounded and really in mourning. I didn't know anyone personally who died. But my son [journalist David Rieff] recently went to the funeral of a Princeton classmate who worked for Cantor Fitzgerald [in the World Trade Center]. A number of people I know lost friends or loved ones.

I want to make one thing very clear, because I've been accused of this by some critics. I do not feel that the Sept. 11 attacks were the pursuit of legitimate grievances by illegitimate means. I think that's the position of some people, but not me. It may even be the position of Chomsky, although it's not for me to say. But it's certainly not my position.

Speaking of your son, he seems to favor a tougher military response to Islamic terrorism than you do.

Well, I don't want to go deeply into it, but clearly we don't see it exactly the same way. Whatever David thinks is tremendously important to me, but we do start from a different point of view. I feel that it's just a difference of emphasis, but without speaking for him, he feels it's deeper than that. But he's still the love of my life, so I won't criticize him.

This is one thing I do completely agree with David on: If tomorrow Israel announced a unilateral withdrawal of its forces from the West Bank and the Gaza strip -- which I am absolutely in favor of --- followed by the proclamation of a Palestinian state, I don't believe it would make a dent in the forces that are supporting bin Laden's al-Qaida. I think Israel is a pretext for these people.

I do believe in the unilateral withdrawal of Israel from the Palestinian territories, which is of course the radical view held by a minority of Israeli citizens, but certainly not by the Sharon government. And it's a view I expressed when I received the Jerusalem Prize there in May, which created quite a storm. But just because I am a critic of Israeli policy -- and in particular the occupation, simply because it is untenable, it creates a border that cannot be defended -- that does not mean I believe the U.S. has brought this terrorism on itself because it supports Israel. I believe bin Laden and his supporters are using this as a pretext. If we were to change our support for Israel overnight, we would not stop these attacks.

I don't think this is what it's really about. I think it truly is a jihad, I think there is such a thing. There are many levels to Islamic rage. But what we're dealing with here is a view of the U.S. as a secular, sinful society that must be humbled, and this has nothing to do with any particular aspect of American policy. In my view, there can be no compromise with such a vision. And, no, I don't think we have brought this upon ourselves, which is of course a view that has been attributed to me.

Let me ask you about another part of your essay that has riled your critics. You said the hijackers displayed more courage than those, presumably in the U.S. military, who bomb their enemies from a safe distance.

No, I did not use the word "courage" -- I did use my words carefully. I said they were not to be called cowards. I believe that courage is morally neutral. I can well imagine wicked people being brave and good people being timid or afraid. I don't consider it a moral virtue.

My feeling about this type of safe bombing goes back to the U.S. air campaign against the Serbs in Kosovo, which I strongly supported, though I was criticized by many of my friends on the left for being too bellicose. I did support the bombing of the Serb forces, because I had been in Sarajevo for three years during the siege and I wanted the Serbs checked and rebuked. I wanted them out of Kosovo as I had wanted them out of Bosnia.

When the U.S. campaign in Kosovo began, I happened to be staying with a close friend in Bari, a town on the tip of Italy, just across the Adriatic from Albania, and the Apache helicopters were literally passing over my head on their way to the airfield outside of Tirana. But, once landed in Tirana, they were never allowed to take off for Kosovo because of the risk that one or more might be shot down and the crew injured or killed. And the U.S. was unwilling to accept these casualties.

But in order to bomb precisely, without hitting hospitals and other civilian targets, you have to fly low to the ground with aircraft like these. And you have to risk being brought down by antiaircraft fire. So I was dismayed by the loss of civilian life in that U.S. bombing campaign, which I had hoped would be very precise.

And so thinking about this, as I was writing my essay for the New Yorker, I became very angry. And I was thinking about the dumping of napalm upon thousands of retreating Iraqi soldiers on the Basra Roa, at the end of the Gulf War -- a slaughter which one U.S. general described as "a turkey shoot." And I wrote, if you're going to use the word "cowardly," let's talk about the people who bomb from so high up that they're out of the range of any retaliation and therefore cause more civilian casualties than they otherwise would, in what has been announced as a limited, focused bombing of military targets only.

What about those in the antiwar camp who see a moral equivalence between the destruction of the World Trade Center and the U.S. bombing of Afghanistan?

That's nonsense too. But, you know, I'm not keen on calling anything the moral equivalent of something else. The world is a slaughterhouse, that's for sure. I'm against mass murder -- not a hard position to take. And here there are two sides, and these are anything but equivalent, morally or in most other ways. But there are not very many strictly military targets in Afghanistan, which is one of the poorest countries in the world. The Northern Alliance, brought to power by American bombs and American money, will not be much of an improvement for the people of Afghanistan. Afghanistan is, has been, is likely to continue to be an ocean of suffering. Afghanistan is not the enemy.

Shares