The waiting game will soon be over.

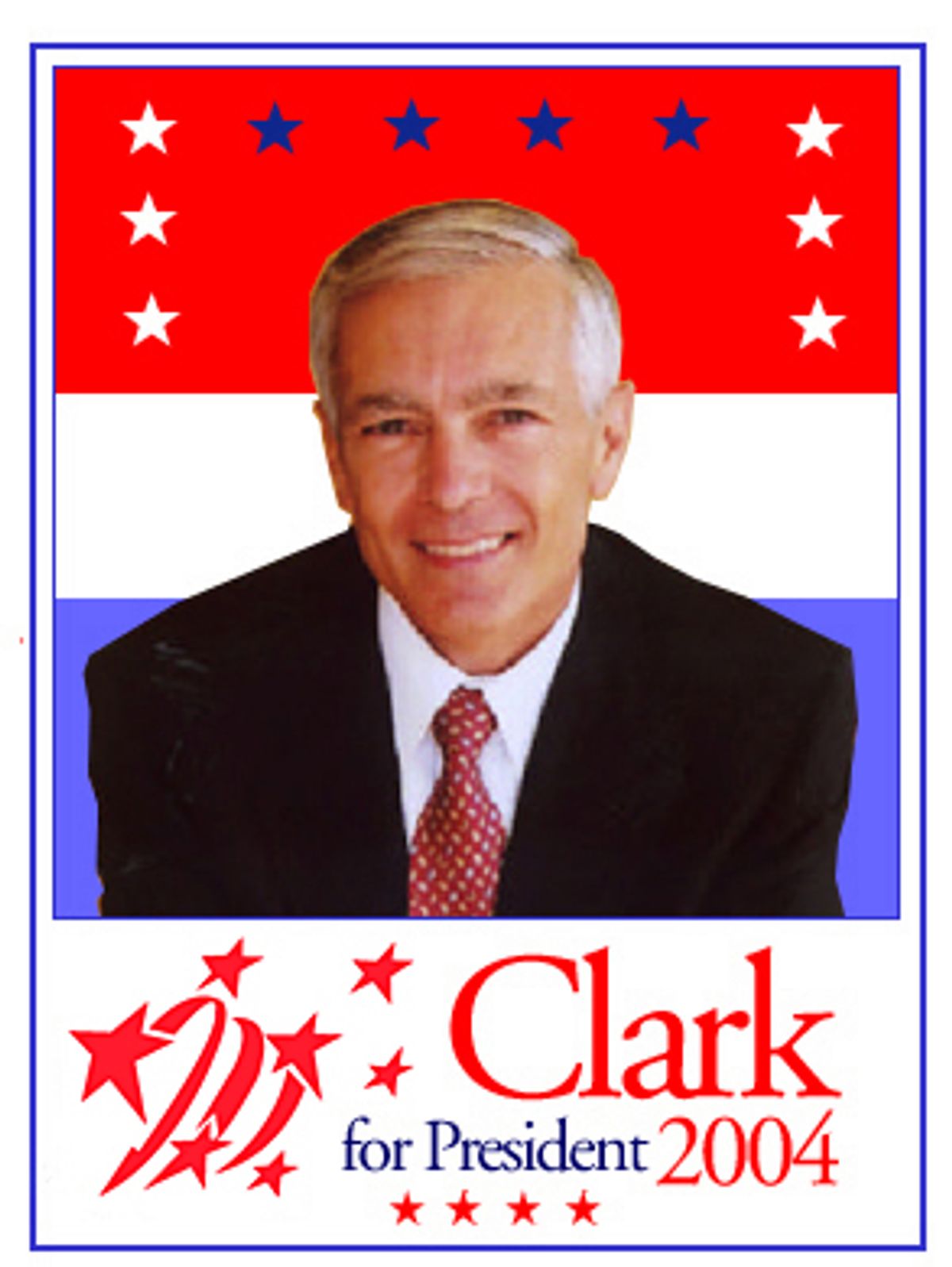

Wesley Clark, retired NATO commander, former CNN analyst, ardent Bush critic, and dream presidential candidate to a lot of wistful Democrats, says he will soon announce whether he is running for president. The guessing has played out for nearly a year as Clark, a political neophyte, has worked behind the scenes, quietly gauging his chances.

On Wednesday Clark officially declared himself a Democrat, telling CNN that if he ran for president, he'd seek the Democratic nomination. "It's a party that stands for internationalism. It's a party that stands for ordinary men and women," Clark said. "It's a party that stands for fair play and equity and justice and common sense and reasonable dialogue." He told the network he hadn't made up his mind to run but added, "I'm closer to working my way through it."

"He's not going to go into battle without an accurate assessment of local troops on the ground, and allies," says John Hlinko, co-founder of DraftWesleyClark.com, one of the handful of grassroots online groups urging the telegenic general to enter the Democratic primary. The organizations do no work directly with Clark and insist they remain in the dark about his intentions to run for president.

His candidacy, this late in the game, would be novel, to say the least.

"He has no political experience, no fundraising, little name recognition, and no endorsements," notes Rogan Kersh, a professor of politics at the Maxwell School at Syracuse University. "In normal times that's a recipe for utter humiliation, and you may as well stay home."

But these are not normal times. This is the first presidential election since 9/11, and terrorism and national security are the issues that reign supreme. "This year the Democrats need some kind of military credentials," insists Kersh, who also notes that the number of undecided Democrats has doubled over the summer.

It's also the first White House vote in 16 years when Democrats won't be seeing a Clinton or a Gore on the ticket. And while former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean has emerged as the Democratic front-runner on the strength of his Internet insurgency and his strong opposition to the war, 50 percent of the Democratic voters in a recent CBS News poll said they wish there were somebody else to vote for.

Those factors point toward a Clark candidacy. "All indications are Gen. Clark is moving forward with a bid," says Larry Weatherford, political director for DraftClark2004.com.

An army of believers is out there. "I really think the Democrats want a winner, and Wesley Clark is the most electable," says Davis Travis, a Wisconsin state representative who was one of Bill Clinton's earliest state supporters in the 1992 presidential campaign. "Republicans are going to try to wrap George Bush in a flag, but I don't think you can make anybody more patriotic than Wesley Clark."

Clark may be hoping that Democrats are so angry about the direction of the country that they'll be willing take a chance on a political rookie with a gold-plated résumé. And one who could win votes in the South. While Dean plays into voters' desire to "take our country back," as he says on the stump, some worry he won't have the electoral reach to do it.

"Democrats know they want their country back, but who's going to get for them?" asks James Zogby. A former senior advisor to the Gore campaign, Zogby also served as deputy campaign manager for Jesse Jackson's '84 presidential run. "Wesley Clark can say, 'I've got the résumé, and I'm more capable of getting it back.'"

And what a résumé it is. A Southerner from Little Rock, Ark., who graduated first in his class at West Point and became a Rhodes scholar, Clark was awarded the Purple Heart in Vietnam. He became a four-star general, later serving as supreme commander of NATO troops, and he defeated Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic and stopped the Serbs' ethnic cleansing of the Albanians.

Clark was also a fervent critic of the war with Iraq, claiming the Bush White House had misled America and needlessly put American troops in harm's way. In the days and weeks immediately following Saddam Hussein's fall from power, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and other allies of the Pentagon derided Clark, although not by name, as a "TV general" who'd lost touch with the realities of war. Fast-forward three months to American soldiers being killed on a near-daily basis, Islamic terrorists pouring into an unstable Iraq, and the reconstruction of that country sucking tens of billions of dollars out of the U.S. treasury, and suddenly Clark's sober warnings appear dead on.

Which is one reason the buzz has been building for weeks. "There's something intriguing about him, and people are talking about Clark all the time," says Ken Sunshine, a longtime Democratic activist who runs a New York City public relations firm and who once served as Barbra Streisand's spokesman. "Obviously he's a smart, capable guy and very attractive on paper."

Esquire magazine has called Clark "handsome, well-spoken, personable, driven, organized, disciplined, passionate, courageous, fair-minded, loyal." The Atlantic Monthly dubbed him "the dream candidate."

But some campaign pros say that dream might turn out to be a mirage. They aren't sure how Clark, if he runs after getting such a late start, will be able to compete from an organizational and financial standpoint. And despite his ubiquitous presence on cable TV and the Sunday morning talk shows, they aren't sure what kind of candidate Clark would make.

"Talk shows are totally different from running a campaign," stresses Zogby. "Tough as [NBC's Tim] Russert is when he wants to be, it's not as tough as shaking hands in New Hampshire and dealing with the press in Iowa. He's going to make mistakes on the campaign trail. The question is, how's he going to deal with them?"

And the question remains, where does an essentially unknown military entity like Clark fit in the primary landscape, and where does he find his core support among Democratic primary voters, who tend to be liberals traditionally driven by domestic concerns?

"I'd argue the Democratic Party has moved to the left, and primary voters are even further. So I don't see an attraction to Wesley Clark for them," says Republican Grover Norquist, a White House ally and president of Americans for Tax Reform. "I'd be surprised if this is a package that sells because there is no underlying pro-military vote within the Democratic primary."

Then there is the simple question of logistics, of putting together the small army of experts, attorneys and advisors that every national campaign must have. "I'm impressed by how daunting a challenge he faces," says Will Marshall, president of the Progressive Policy Institute, a centrist Democratic think tank. "He's a brilliant man and I don't want to underestimate him, but the fundamental question is, is it too late? If he'd entered the race two or three months ago, he could have had a big impact."

(Clark backers like to point out that in '91 Clinton did not enter the presidential race until October. But he faced a weaker field than Clark would, and certainly nobody who had accumulated the kind of war chest that Dean has.)

As far as raising the millions of dollars needed to feed a national campaign beast, "the fundraising game is getting late and it's not easy," warns Sunshine, who has contacts within Democratic circles in the fertile fundraising territory of New York's Upper East Side, where some leading donors are already committed.

A source associated with one of the Democratic candidates doubts Clark will enter the race. "I think he'll play it out and get attention and make himself the front-runner for the vice presidency."

If Clark does jump in, "after a couple weeks it will be pretty apparent that he is not necessarily a top-tier candidate," says the Democrat insider. "Because he'll wake up and realize, I have to raise $32 million and get on the ballot in 50 states. That's hard to do. He's known to you and me and a couple hundred people in Georgetown. But he does not have high name recognition in Iowa and New Hampshire. He needs TV, an organization, and all that stuff has to be done flawlessly for him to succeed."

Some independent observers offer up similarly chilly assessments of Clark's chances. "I don't expect him to make much of a splash in New Hampshire," says Dante Scala, a professor of politics at St. Anselm College in Manchester, N.H. "I think he's missed the boat. The underlying notion behind Clark is that there's a vacuum in the race that needs to be filled by somebody. But Howard Dean has filled that vacuum. Clark looks like a good candidate on paper. But John Kerry is finding out résumé candidates have a hard time against message candidates, and Howard Dean is the [antiwar] message candidate," Scala says.

"There's still time, but it's only going to get noisier in New Hampshire," Scala says. "Kerry and Gephardt and Edwards all have ads up now. For a first-time candidate like Clark to be able to cut through all those rival messages and media clutter, that takes a special kind of person."

Clark's backers, many of whom have been flocking to the Internet in hopes of creating a cyber support crew that could be built into a brick-and-mortar infrastructure if the general decides to run, argue Clark is that special kind of person.

"Look at all the candidates and then look at Clark. Who appears to have that intangible charisma? I'd argue it's Clark," says Hlinko. "He's an incredibly likable guy. He's clearly bright. He really has a sense of being presidential, and people are comfortable with that."

If that comes across on the campaign trail, if Clark turns out to be a natural on the stump, relishes working the rope line, and quickly forms a top-flight campaign crew, he has the power to alter the primary race, and to do it quickly.

"If Clark sustains momentum, he drives out candidates quicker than Iowa or New Hampshire will," says Zogby, currently president of the Arab American Institute. "He has the ability to make it a three-man race: Dean, Clark and Gephardt, who isn't going anywhere with all those union endorsements."

Observers suggest Kerry, busy touting his own military record, has the most to lose from a Clark candidacy. "Kerry says, 'I'm the liberal with the military background who can't be out-militaried by Bush and the Republicans.' Clark steps in and says, 'Me too. Plus I'm a Washington outsider,'" says Norquist.

But how does Clark, parachuting into the race, strip away Dean voters, especially in the key early primary states? Clark supporters insist that Democrats wary of Dean's chances against Bush (that is, a conservative wartime president versus the former governor of Vermont) would flock to Clark and his electability.

But unlike any other candidate, Dean seems to have formed a bond with his supporters, often because he was, it seemed at times, the lone candidate rallying against the war with Iraq during the months of January, February and March. "Dean played to the emotions of peace activists and the anti-Bush sentiment within the party, emotionally and viscerally," says Marshall. "Could Clark take those people away? I doubt it, because they're antiwar, period. He's got to arouse passion on his own and persuade doubters, make them think he's better than their first choice."

Norquist the conservative argues that to do that, Clark would have to out-Dean Dean -- and would lose something in the process. "I think Democrats feel robbed about the 2000 election and locked out of the Senate and House," he says. "They're just livid and want to go with guy who hits Bush the most, and that's Dean. If Clark turns into that 'I hate Bush, too' candidate, if he has to match Dean's rhetoric, he'll become unhinged, and voters will have lost what they thought they were buying with the moderate guy who wears the military uniform."

Nonetheless, Norquist concedes that if the general does win the nomination, "It's very possible Wesley Clark would be in better position to beat Bush than Howard Dean."

"That's the scenario the White House most fears," says Weatherford at DraftClark2004.com. "Because they can't attach their favorite labels to Gen. Clark."

Shares