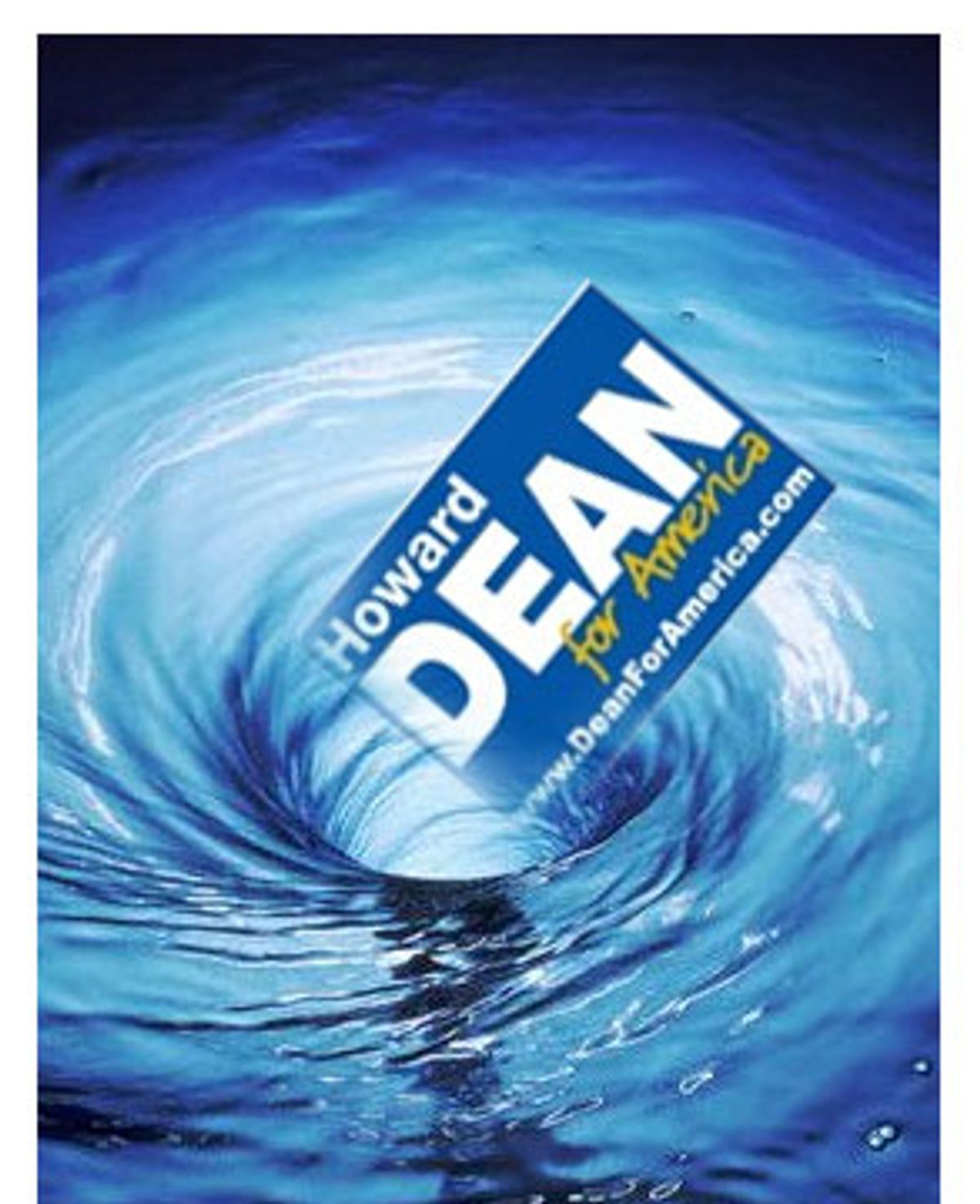

After suffering double-digit losses in both the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary, Howard Dean's presidential campaign is now on its heels.

Although it continues to raise money at a furious pace, Dean has spent most of the $41 million he raised in 2003. In a major shake-up, campaign manager Joe Trippi departed last week after Roy Neel, a shrewd and capable Al Gore loyalist, was hired as chief executive officer of a campaign that is suddenly unsure of itself. Consider that in a matter of less than 10 days, the message from the campaign's leadership went from Trippi snidely asking how Dean's competitors thought they could compete nationally with the Dean juggernaut in the seven primaries held on Feb. 3, to Neel's concession that Dean is unlikely to win any of those seven contests.

Nobody can doubt that the Trippi-led Dean campaign transformed forever the ways in which public support for political candidates is cultivated. The campaign's pioneering effect is obvious to anyone who watched the other candidates' Web sites gradually morph into Dean for America imitators. So how and why did the Dean campaign implode so quickly?

Trippi achieved rock-star status as the prophet of the new politics, and it is tempting to simply blame him and his consultancy partner, Steve McMahon, for Dean's reversal of fortunes. Trippi may find it equally tempting to shift the blame to other campaign operatives, or even to Dean himself. When the inevitable finger-pointing begins, both Trippi and Dean would be wise to remember a maxim that coaches often use to remind their athletes of its perils: When you point a finger at somebody else, you always have three pointing right back at you.

I have openly supported Howard Dean's campaign. I attended meetings, house parties and rallies during 2003. I contributed money and encouraged friends to do the same. I have spoken at length with some of the campaign's key backers and strategists, and in Iowa and New Hampshire I observed the campaign's operations at the ground level. Although none of what follows reveals information or reactions provided to me off the record, these are the conclusions of a participant-observer who wishes things had turned out differently.

The first mistake Trippi made was in confusing the qualitative value of Dean's political support with such quantitative indicators as the Dean Web site's ubiquitous fundraising "bat" totals, the latest Meetup.com and house party attendance figures, or the campaign's growing list of official endorsements. These innovations did not enable Dean to translate his support into the only electoral commodities that ultimately matter: votes and victories.

Andy Stern, president of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) -- which bolstered Dean's candidacy and the legions of foot soldiers when it joined the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) last fall to co-endorse Dean -- distinguishes between "activity" and "movement." During a New Hampshire bus ride, as he reflected on Dean's disappointing third-place Iowa finish, Stern told me that the Dean campaign had shown a capacity for the former but not the latter. Sen. John Kerry had won in part because his campaign focused its more limited resources on a far more effective and efficient field campaign that emphasized "hard counters" -- local precinct captains with the credibility and connections to generate movement.

Overconfidence induced by the sheer level of campaign activity begat Trippi's second trip-up: The misallocation of resources spent to satisfy the campaign's supporters rather than to search for votes. The most glaring example of this meta-campaign was the "Perfect Storm" program developed to flood Iowa with thousands of volunteers in the days before the caucuses. To get a firsthand view, I participated in the Storm's training program; it was quite impressive in its format, although many of the trainers were themselves volunteers who clearly had less field experience than I did.

Worse, the abundant orange hats in Iowa created the impression that the Dean campaign was less concerned with the issues that mattered to Iowa's Democrats than the enthusiasm of the non-Iowa political tourists. The campaign wasn't oriented in the local, native way that best resonates with actual caucus-goers. In an obvious change of tone, Dean's New Hampshire state director, Karen Hicks, made plain to the media that the only orange hats in her state arrived on the heads of people who came from Iowa.

Trippi's final error -- and the one that Dean loyalists at the highest level of the campaign forgive the least -- was his decision to use negative television ads to revive Dean's plummeting fortunes in the final days before the Iowa caucuses. Those ads were intended to regain Dean's singular status by reminding voters that his three main Iowa opponents -- Kerry and fellow Sen. John Edwards, and Rep. Dick Gephardt -- all voted for the Iraq resolution.

But the ads backfired because they reinforced a growing impression that Dean had a surly temperament and was easily goaded (by Gephardt, especially) into the ugly campaigning that many voters disdain. Some inside the campaign were upset with Trippi and McMahon about the quality of the ads but have defended them and the firm's billing rate for placing them.

Many of the amazing successes of the middle six months of 2003 -- most notably the record-setting fundraising dollars generated online -- are rightfully Trippi's to claim.

Trippi is also correct to complain about the destructive forces that remained beyond his control, especially Gephardt's attacks and the media's often too harsh scrutiny. Still, Trippi's core failure was his inability to figure out how to convert the activity he had helped Dean generate into real movement.

Trippi's tactical oversights were compounded by three very costly mistakes Dean himself made.

Obviously, Dean's first failure was not recognizing the limitations of Trippi's stewardship. Had he done so, he might have supplemented Trippi's work by appointing a Neel-like manager to supervise the small but critical details that Trippi was either unable or unwilling to execute. The campaign had the resources; plenty of able applicants would have jumped at the opportunity. Although the media would have hammered Dean for the hypocrisy of hiring a Beltway insider at the same time he was mocking his Washington opponents, that kind of negative press would have been manageable and would have quickly blown over. Twenty-point losses in Iowa are a much tougher spin and leave no time to recover.

Asked by "Meet the Press'" Tim Russert on Sunday about Neel's hiring and Trippi's departure, Dean said:

"It does help to have somebody who knows something about how to run campaigns organizing your campaign. It had been my hope that Joe would have stayed on because he's such a brilliant strategist, and he built the campaign. And I think that would have been a tremendous team -- to have Roy running the inside stuff for the campaign, making sure that the trains run on time, and having Joe's brilliant strategy from the outside."

What's more, Neel almost certainly would have checked Dean's impulses to pick unnecessary fights with, well, whatever target piqued his momentary interest. In the longer run, Neel's insider savvy would have dulled the press knives a bit. And anybody who suggests that Neel's arrival would have turned off the Dean faithful doesn't fully comprehend the nature of Dean's followers.

Dean has long relied on a very tight circle of close advisors who have ably served him, headed by his longtime aides and confidantes, Kate O'Connor and Bob Rogan. But if Dean could not see the need for some outside help -- or, worse, if he recognized the need for help but couldn't bring himself to ask for it -- he has only himself to blame. In a cheeky Washington Post opinion piece a month ago, Marjorie Williams says she only fully understood Dean's demeanor when she remembered that Dean is a doctor. However good Trippi's advice to Dean may have been, the doctor should have sought a second opinion.

Dean's second error was his failure to continue the steady and successful evolution of his candidacy. Throughout most of 2003, Dean demonstrated an uncanny mix of political gumption and presumption. When nobody knew who he was, Dean behaved as if he belonged onstage with the better-known candidates, and soon enough he was legitimate contender. When critics doubted his ability to raise money, Dean outpaced them all, often cumulatively, and without competing for the $2,000 checks the others relied on. When cynics questioned his ability to garner union support or political endorsements, he surprised everybody with one press conference after another to announce his growing roster of supporters. Dean partly became the front-runner because he acted as if he deserved to be.

Once he reached the front of the pack, however, Dean's one-stage-ahead-of-himself progression began to stall. By mid-autumn 2003, instead of exhibiting the subtle moves of a future nominee, Dean was stuck. He should have transformed himself, by moving simply from diagnoses of what was wrong with the Democratic Party and the current administration to prognoses. Only in the week between Iowa and New Hampshire did Dean return to the themes of fiscal management and his healthcare successes in Vermont, but it was too late. (And his televised "scream" drowned out his new -- or, rather, original -- message.)

By the time of the Iowa caucuses, Dean's insurgent talk was not only redundant for those already supporting him, it clearly turned off many of the anybody-but-Bush Democrats still shopping around for what they hoped would be the party's most electable candidate. The most telling statistic heading into Iowa came from a Zogby poll showing Dean fourth -- with just 13 percent -- behind Kerry, Edwards and Gephardt as the second-choice candidate among Iowans who preferred somebody else. With all due respect to Paul Begala, who told me in the Val Air Ballroom that he believes Dean faltered because he lost his insurgent's edge, Dean's fall was precipitated by his failure to lose that edge sooner and start acting more like the nominee he aspired to be.

Dean's third major error was to continue emphasizing his antiwar position above all his other positions. Dean deserves credit for showing the courage to criticize President George W. Bush about Iraq when others were too timid to do so. Though many Democrats eventually arrived at the same conclusions as Dean about the war, polls from autumn 2002 indicate that many Democrats did not start where Dean started. Put another way, the evolving views of many Democrats on the Iraq issue more closely mirror the political journey of Kerry or Edwards.

The conventional wisdom is that a "dated Dean, married Kerry" buyer's remorse sank Dean. It's an apt concept but wrongly applied. If Dean's steadfastness on Iraq evokes buyer's remorse among mainstream Democrats, it's because Dean reminds them that they bought Bush's justifications for invading Iraq and now regret it. Kerry's evolution may have been purely opportunist; indeed, his tough talk on Iraq came only after Dean proved it was politically viable. But Kerry's fickleness became an unexpected blessing because his shifting stance has affirmed many voters' feelings about the war, whereas Dean's consistent and insistent opposition may create an uncomfortable dissonance.

What happens to Dean if his long-shot Wisconsin-Michigan-Washington strategy fails and Kerry (or Edwards) captures the nomination?

Dean says he will fall in line behind whomever the Democrats nominate and will encourage his loyalists to do the same. If Kerry is smart, he will avoid the temptation to respond to Dean's attacks and instead reach out to Dean's supporters. After all, in many ways Dean made the nomination a more attractive prize by almost single-handedly picking up a defeated Democratic Party, dusting it off, and putting it squarely into the national partisan fight again. The painful irony for Dean is that he is unlikely to get the chance to be the Democrats' man in the ring for that fight.

On "Meet the Press," Dean noted grudgingly that the other campaigns have stolen or borrowed his themes. He and Trippi knew they had created something special. It's a shame they didn't quite know what to do with it.

Shares