The Bush campaign claims no connections to the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth and their mission against John Kerry. It's just one big happy coincidence. Those Republicans just have all the luck.

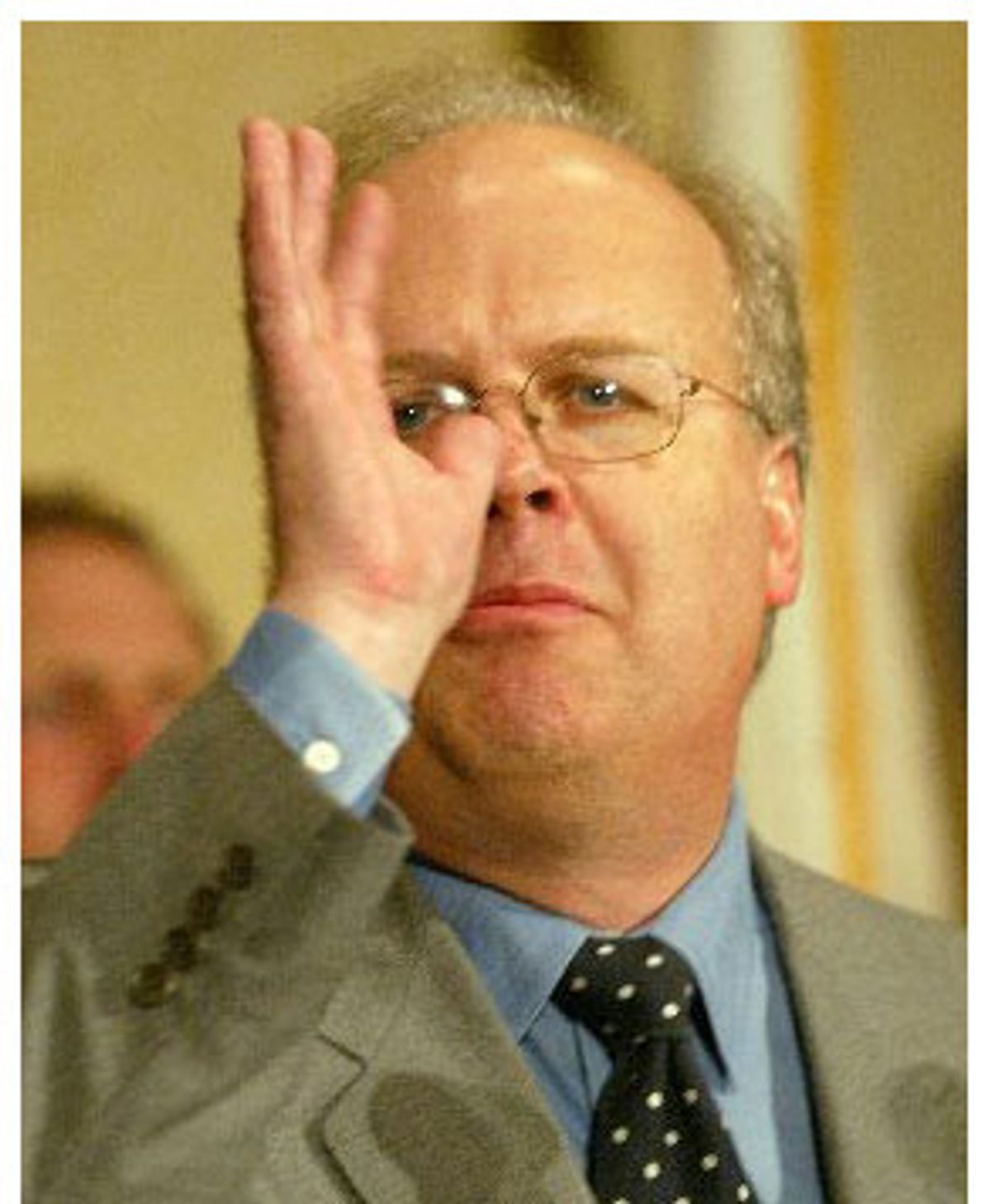

But it is a politically fatal form of naiveté to think senior Bush political strategist Karl Rove has been sitting idly in his West Wing office hoping that a group might spontaneously arise to question John Kerry's credibility as a commander. The Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, the whisper campaign against Ann Richards that questioned her sexuality, the attacks on John McCain's mental health in South Carolina, and the questioning of his environmental record in the New York primary were all products of the fastidious work of Karl Rove. And it does not take an FBI agent to make the connections.

The big moneyman behind the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth is Bob Perry and, not surprisingly, the only visible connection between Perry and Swift Boat accuser John O'Neill is their mutual relationship with Karl Rove. Perry worked with Rove early in the consultant's political ascension. The Houston homebuilder, who has developed into the biggest giver to Republican causes and candidates in Texas, was the finance chairman of the 1986 Texas gubernatorial campaign of Bill Clements. Rove managed that race for Clements and Perry was an important fundraiser, helping Rove generate the donor lists he used to rebuild the Texas Republican Party, and, ultimately, finance the climb of his prize client, George W. Bush.

Rove had already convinced Perry to begin raising money to elect state judges -- funds used to help launch the Texas Civil Justice League. The Civil Justice League was Rove's initial surrogate organization and carried the message that trial lawyers were bad people who were screwing up the business climate with frivolous lawsuits. The chorus singing about the evils of lawyers in Texas was later joined by Citizens Against Lawsuit Abuse (an organization that Rove helped grow and with which he maintains close contact today), and yet another front group called Texans for Lawsuit Reform. As they chanted their messages across the state about the horrors of litigation, Rove's political clients were able to publicly acknowledge the concerns of these groups. Thus an entirely artificial movement, conceived and funded by Rove, was used to change the state's judicial system and, of course, became an essential step in Rove's master plan to elect Bush governor and then president.

The Swift Boat Veterans for Truth is nothing more than another example of Rove's tactic of using surrogates to do his candidate's dirty work and there is a clear, bright line running from the current headlines back to Texas. When it came time for an organization like SBVT to magically appear, Rove already was the acknowledged master of the third-party surrogate slur. As he was rebuilding the Republican Party in Texas, Rove developed a template for smearing opponents. The goal was to have his candidates hover above the fray while urging their opponents to concentrate on issues, thereby constantly putting them in a position of having to play defense and deny unfounded accusations. Eventually, the Rove client, according to the script, would step out to demand an end to the ugliness. Of course, Rove wrote the narrative of these plans in such a way that calling for a truce would not occur until the damage had already been done to his opposition.

The attacks on John Kerry's war record fit like a mass production mold with Rove's political campaigning. While great armies probe an enemy's defenses for weaknesses, "Bush's Brain" has always tried to batter his opponents where they are strongest. Kerry's profile as a combat-tested officer ready to assume the role of commander in chief was a problem for the Bush campaign. So Rove went after it. "Look, I don't attack people on their weaknesses," he once told reporters in Texas during a campaign. "That usually doesn't get the job done. Voters already perceive weaknesses. You've got to go after the other guy's strengths. That's how you win."

Ann Richards was a socially progressive and inclusive governor of Texas, appointing a few gays and lesbians to state boards and commissions. In 1994, Rove pinpointed this as an issue certain to help George W. Bush win election in a conservative state. Of course, Rove was not about to let his candidate broach the subject himself. Instead, he worked through Republican operatives in East Texas. Rumors soon began to circulate through coffee shops and agricultural co-ops that implied Gov. Richards, an unmarried woman, might be a lesbian. Without identifying the topic, she acknowledged she was being hurt. "You know what it's about," she told reporters, dismissively, after being asked about the rumors. "And I'm not talking about it."

But Republican state Sen. Bill Ratliff from East Texas, who was also Bush's regional coordinator for that part of the state, was quoted in newspapers as criticizing Richards for "appointing avowed homosexual activists" to state jobs. The rumors were then given a form of legitimacy and widely reported. Then just as he did with Kerry and the Swift Boat controversy, Rove had Bush step forward as a voice of understanding and reason. "The senator doesn't speak for me," Bush told reporters. "I don't know anything about what he's talking about. I'm trying to run an issues-oriented campaign."

When Rove and Gov. Bush stepped onto the national stage in 2000, they had a big list of supporters, money and infrastructure that had been systems-checked in Texas. And they would use it to win by any means necessary and not fret over the ethics. Flying down to South Carolina after the upset defeat of Bush in the New Hampshire primary, Rove and Bush were said by a reliable source to have had a frank conversation about what was necessary to defeat Sen. John McCain, who had just defeated Bush in New Hampshire. A summit meeting was convened in Columbia and Rove delivered the message to the campaign operatives.

The candidate also tipped his hand to the strategy when he was overheard on a boom mike explaining his plans to Mike Fairs, a state senator. Fairs complained that Bush had not yet hit McCain's soft spots. "I'm going to," Bush said. "But I'm not going to do it on TV."

Because that's not the Rove way. Before the votes were cast, McCain was accused by Rove-managed surrogate groups of fathering a mixed-race child out of wedlock, being married to a drug addict, not being an attentive husband, using his wife's family fortune to buy his U.S. Senate seat and, worst of all, turning his back on Vietnam veterans; and all of this happened while George W. Bush was at rallies urging his primary opponent to please engage in a civilized debate on the issues.

Most of the accusations against McCain were contained in a World Magazine article, a weekly publication for Christian evangelicals. The magazine was edited by professor Marvin Olasky, an ideologue at the University of Texas -- a Communist Party member turned Republican, a Jew turned born-again Christian -- who had been recruited by Rove to refine his concept of "compassionate conservatism."

The vets' group denouncing McCain on behalf of Bush and Rove, the National Vietnam and Gulf War Veterans Coalition, was fronted by J. Thomas Burch Jr. Many of its members were driven by an obsession that there were still live Americans missing in action in Vietnam and McCain was failing to bring them home. McCain had considered that question resolved and had done his part as an elected representative and former prisoner of war to heal the war's losses. This was apparently the improper approach according to Burch, whose group was accused by McCain's camp of spreading rumors emanating from Karl Rove about the senator's mental stability after years in solitary confinement in a North Vietnamese prison.

When Wayne Slater, a reporter for the Dallas Morning News, wrote that the whisper campaign in South Carolina about McCain's mental health fit with previous Rove tactics in Texas, such as the whispers about Ann Richards' sexuality, Rove confronted the reporter on an icy tarmac in New Hampshire. "You're trying to ruin me," Rove hissed. "My reputation. You son of a bitch. It's my reputation." Bush, for his part, was less defensive. Not only did he refuse to denounce the fringe veterans' organization, he embraced its endorsement and dismissed McCain's complaints. On stage before the primary debate in Columbia, an enraged McCain confronted Bush. "You ought to be ashamed, George," McCain said.

"Senator, it's just politics," Bush answered.

"Everything's not politics, George."

At the media center in a Columbia hotel on primary night, it was obvious Rove's smear strategy had succeeded. When he passed my television crew's location on the riser, I acknowledged his achievement. "Congratulations, Karl. Looks like you did it."

"Hey, don't congratulate me," he said. "It was the candidate who won. He did it. Not me," Rove said.

"Sure, Karl. Whatever you say."

The tarnishing of John McCain's impeccable military service turned out to be tepid compared to how the Republicans and their surrogates, led by Rove, smeared Sen. Max Cleland of Georgia in the 2002 midterm elections. Cleland, who was one of the first senators to propose and begin drafting a measure for a Department of Homeland Security, had his concern for the country's safety turned into a political liability by Rove. Under Rove's guidance, Bush initially stated the U.S. government did not need another gigantic bureaucracy like Homeland Security. But Rove's polling discovered there was significant public support for the idea and he quickly got a group of Republican lawmakers to cobble together their own bill. However, Cleland voted against the Bush version because it included measures that drastically reduced the ability of federal employees to bargain for better wages and had removed key provisions that Cleland believed would make the new agency relatively ineffective. Hitting the campaign trail for reelection, Cleland, who left two legs and an arm in Vietnam, discovered that he was being called unpatriotic by his Rove-advised opponent, Saxby Chambliss, who never served in the military. A TV advertisement morphed Cleland's face with those of Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein. "Where does this take us?" Cleland asked me in an interview last year. "What good does this do for us as a country? I've been through worse before. I've lost limbs. But what about the people who are coming up and are thinking about public service? What are they going to think about it as their future? What does this say about our country?"

John McCain might well consider asking the same questions instead of standing at the side of the president at political rallies. When he calls the SBVT ads against his friend John Kerry "dishonorable and dishonest," he might add who he thinks is behind them.

In addition to his military résumé, McCain's other great strength as a political figure has been his call for campaign finance reform. Revisions to those laws were a threat to the way Rove and his clients conducted their fund-raising affairs. Before the 2002 primary campaign had reached New York, Rove had already dipped back into his Texas well of money and power. Suddenly, without explanation, an organization appeared on the scene that wanted McCain defeated and, of course, had nothing to do with the Bush campaign.

The front group called Republicans for Clean Air spent $2.5 million on television ads in New York to attack McCain's environmental record. This "independent" political action committee was simply two Dallas businessmen, Charles and Sam Wyly, who had given more than $200,000 to Bush's gubernatorial war chests. Charles was also a Bush "Pioneer," after raising more than $100,000 for the governor's presidential run.

The Texas GOP consultant who worked on developing the ads was Jeb Hensarling, a longtime business associate of James Francis. Francis was Karl Rove's mentor when they worked together on the first Bill Clements gubernatorial campaign. Francis is also one of George W. Bush's closest personal friends.

When reporters began calling to find out about the group distorting McCain's voting history on the environment, a public relations firm headed by Merrie Spaeth was hired to deal with the media. Spaeth, as has been reported, handled P.R. for the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth and helped with early strategy meetings -- and in an earlier campaign had coached George H. W. Bush in his vice presidential debate preparations. She was married to the late Tex Lezar, who ran as lieutenant governor in 1994 when Bush first campaigned for governor. Lezar also was a senior partner in the law firm that found a place for John O'Neill.

When Republicans for Clean Air was exposed, the Wylys claimed they were pushing for, well, clean air. But there was a back story. When Gov. Bush privatized the University of Texas Investment Management Company, the managers he appointed placed $90 million of the university's endowment with Maverick Capital Fund. Maverick was founded and majority owned by the Wylys, who earn about a million a year in fees for managing the U.T. money, as well as a healthy percentage of any profits.

This is the way it works in Texas -- and, if it is up to Karl Rove, how it works in the rest of America.

Shares